Words that make objects appear from thin air are generally the stuff of the magical worlds of Harry Potter or The Hobbit. But a new experiment has been shown that words can make objects easier to recognise, as our sense of vision can be altered by other sensory inputs.

“People assume that vision is the most impervious of the senses, impenetrable to outside influences,” said Gary Lupyan of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who led the research. But evidence is growing that shows external information can change what one sees.

Lupyan wanted to know how much of what we see is affected by factors outside of vision. “For example, when you see lights flashing in a club, they appear to be playing in time with the music. Actually, in most cases, the lights aren’t doing that. The visual system adjusts what you see. In terms of timing, people have more accurate hearing, and thus what one sees gets alters accordingly,” Lupyan said.

In the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Lupyan used equipment that showed different things to each of a participant’s eyes. One eye was shown an image (a kangaroo for example) and the other a series of continuous flashes. The flashes suppress the visual perception of whatever object was being presented to the other eye.

Then Lupyan asked the participants whether they saw the image. He found that participants were far more likely to recognise what they were seeing if they heard a valid verbal label, such as the word “kangaroo,” before the task. And they were less likely to see the image if the word they heard was irrelevant.

This is not because the word prompted the participant to recover something they had seen subconsciously, Lupyan explained. “The flashing technique disrupts vision at a very low level. This means that there is no signature of any subconscious cognitive processing of the image. So the word (the label) actually gets into visual system itself.”

These findings suggest that language can give a boost to perception — relevant words changed what participants saw. This idea has widespread ramifications. It implies an intensely interactive network between “lower level” senses and “higher level” cognitive functions, a network that works both ways.

Dan Mirman of the Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute studies language processing. He explained that, “There are two ways of thinking about perception and cognition. One takes the view that there are progressive levels of processing information that go from simple perception to more complex cognition. However, the other option is to see these levels as all working together.”

“My work in speech and colour perception argues for this interactive view, as does this research,” Mirman added. “Visual processing and language are normally studied completely separately. This study has shown that these things interact very directly.”

This research therefore allows us to question whether language literally changes what we see; that is, naming an object evidently affects visual representations in some way. “What does having language mean in this context?” Lupyan questioned. “It evidently has far more than a communicative function.”

“Humans are the only animals who have an evolved language. We can teach this to other animals to some degree. Parrots and dogs, for example, can learn to associate objects with a label. But not in the wild.”

“It seems these labels may allow an animal to perceive in a completely different way — in categories. Language in some way abstracts us away from particulars, from detail.”

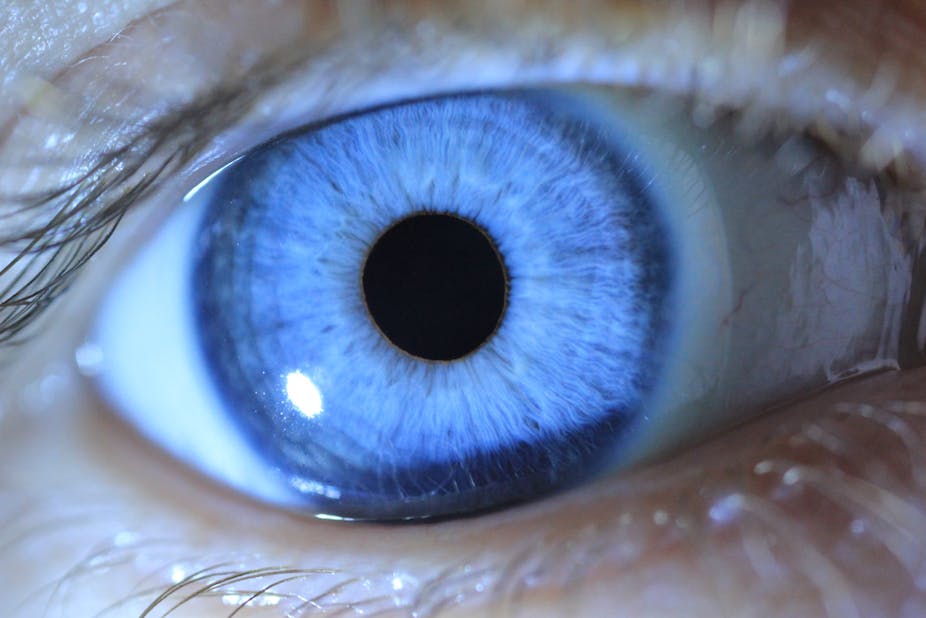

This brings up another possibility. If these labels are not just a shorthand, but actually affect how we perceive, as Lupyan’s experiments suggest, then do people who speak different languages see and remember things differently? Other research suggests they do. Russian speakers, for example, have two different words for the colour blue. These labels change how Russian speakers perceive and understand colour.

“You might,” Lupyan concluded, “compare the difficulty in translating poetry. Some subtle emotion or meaning is always lost. What if we see substantially differently in different languages, in a way that is similarly lost in translation?”