Do-it-yourself bloggers, video diarists (vloggers), artists with their pixel-palettes of innumerable hues, sounds and images – the explosion of online content creation is one of the contemporary wonders of the world.

User-generated content (UGC) and their applications are by far the largest type of online content, both now and in any foreseeable future.

The latest guesstimate on US online content suggests that more than 70% of the digital universe is generated by users – individuals at home, at work, and on the go.

That’s 880 billion gigabytes!

But this flowering of creativity is not met with unalloyed enthusiasm.

The vast and growing phenomenon of UGC suggests significant dissatisfaction with what mainstream media is offering, particularly among digital natives who have grown up with the net.

And the way is it rapidly being monetised can also be seen as threat to established business models in the creative sector.

This is exacerbated by the parallel growth of piracy and other ‘informal’ uses of copyrighted creative content.

Leading digital futures thinker Charles Leadbeater has recently warned that major upgrades of the broadband infrastructure in ‘Digital Britain’ will accentuate UGC and ripped content, at the expense of the copyright industries.

And here in Australia, there is criticism of the National Broadband Network (NBN) that faster broadband just means a faster means of downloading porn, or that ‘mere’ home entertainment will be the major beneficiary of such a huge public outlay.

But let’s look closer at what’s going on.

Piracy - really such a scourge?

First, we must confront the question of piracy. There has been an explosive growth of piracy as digital technologies became cheap and ubiquitous around the world, which has been followed by a corresponding ramp-up of law enforcement around copyright protection globally.

An independent, large-scale study of music, film and software piracy in emerging economies was discussed at a recent roundtable hosted by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation.

The findings of “Media Piracy in Emerging Economies” show clearly that, rather than piracy being “a global scourge”, “an international plague” and “nirvana for criminals”, it is largely a global pricing problem.

According to project director, Joe Karaganis, the choice isn’t between high piracy and low piracy in most media markets.

“The choice, rather, is between high-piracy, high-price markets and high-piracy, low price markets,” he says.

Nothing will change until either the major rights holders of music, film and software lower their prices to make legal purchases a possibility in low income countries, or the middle classes of those countries grow large enough to be able to afford them.

In the meantime, it is the case that rigorous independent studies show that piracy can generate a significant ‘consumer surplus’ (industry losses versus consumer gain) estimated in 2009 in the Netherlands to be 100 million euros annually.

Second, we need to look closer at what is happening under the bonnet, as it were, of creative culture online. It is teeming with innovation, a fresh ground-base from which new ways of producing, distributing and consuming creative content have ensued, and which offer to answer Karaganis’ challenge that media businesses must find a way to survive in these environments.

YouTube generation

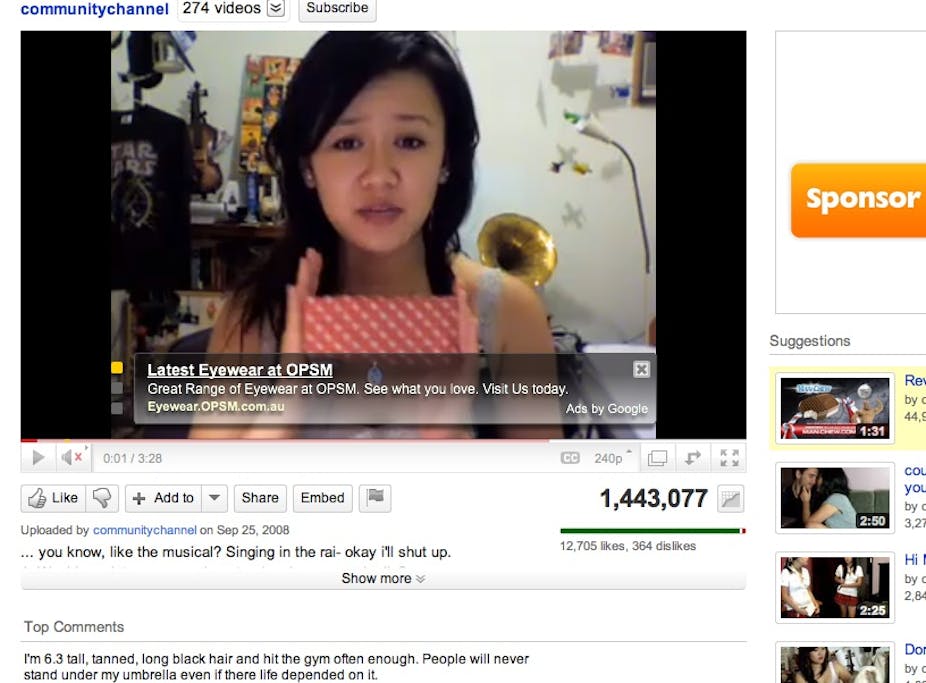

If we take by far the biggest online repository of UGC in the world, YouTube, we see it looking to turn gifted amateurs into remunerated practitioners while at the same time cleaning up its large swathes of ripped content.

While it remains largely a huge repository of amateur work, it is now rapidly evolving into a site that is contracting mainstream content, shoring up its adverting base, and instituting a key innovation in the copyright wars with ContentID.

Learning from the heavy duty litigation of the Napster era, this software indentifies copyrighted content and offers the rights-holder a shared advertising revenue solution rather than a judicial solution such as take downs or legal action.

YouTube faced a big problem as its popularity grew. The cost of servicing their legions of users could only be offset against revenues from advertising. Advertisers wanted their ads placed next to legal and ideally professional content, while the real rates of growth were in amateur content.

A strategy for better marrying amateur content and online advertisers was necessary. “De-piratising” YouTube has gone hand-in-hand with offering amateur content makers the chance to make a living out of their attractiveness to the YouTube user base.

YouTube has developed its Partnership Program for sharing revenue with popular content creators, and has just acquired content creation company Next New Networks to feed into the process.

Old paradigms

Third, we need to consider what industry and government can do. Younger generations in the creative industries are already well into fashioning new business models.

Filmmakers are becoming ‘transmedia’ producers, finding ways to create value out of multiple platforms, communities and audiences.

The old defence of professionalism is being overtaken by new modes of value creation through deep engagement with social media. Old oppositions like ‘community versus commercialism’, ‘professional versus amateur’, ‘entertainment versus education or information’ don’t work in this transmedia space.

It is a space where copyright control regimes are less important than socially networked touchpoints into multiple potential markets; where weak IP (everything can be replicated rapidly by competitors) means rapid exploration of new ways to manage risk.

These issues are central to government policy. As the largest nation-building project in Australian history, the NBN has built into it an expectation that there will be huge opportunities.

As the Federal Communications Minister, Senator Stephen Conroy remarked, internet commerce has created new business models, improved productivity in a variety of retailing sectors (for consumers particularly), and given small business huge opportunities to access new markets.

Testing nerves

Let me give an example: online distribution of film, and opportunities for Australian content.

A politician or pundit can always make the cheap point about ‘all this effort and just for faster (ripped) downloads of your favourite movie?’

Despite the hype, online distribution of film is an extremely difficult business to make work at present, and the opportunities for (legal) Australian content online is even more tenuous. Everyone knows that the NBN or similar fast broadband solution will transform the screen distribution industry, render the neighbourhood video store redundant, and open a space for better access to local content. But it is the getting there that will test every entrepreneur’s nerves.

Worldwide as well as in Australia, many experiments in making (legal) online distribution of film have crashed and burnt. At present, you can get movies online for purchase or rental through major players like iTunes, or Telstra T-Box, or through new or remodelled companies like Quickflix, Fetch TV, Hybrid TV/Caspa on Demand. But our research into available Australian content is not encouraging.

Figures change all the time, but a snapshot showed less than 0.5% on iTunes, 34 titles visible online on BigPondMovies, Quickflix estimates 1-3% of its catalogue to be Australian.

Here we see in its raw form new opportunities, new business models, but also both old and new obstacles to the delivery of Australian cultural content online.