Nations around the world are rapidly developing high-energy laser weapons for military missions on land and sea, and in the air and space. Visions of swarms of small, inexpensive drones filling the skies or skimming across the waves are motivating militaries to develop and deploy laser weapons as an alternative to costly and potentially overwhelmed missile-based defenses.

Laser weapons have been a staple of science fiction since long before lasers were even invented. More recently, they have also featured prominently in some conspiracy theories. Both types of fiction highlight the need to understand how laser weapons actually work and what they are used for.

How lasers work

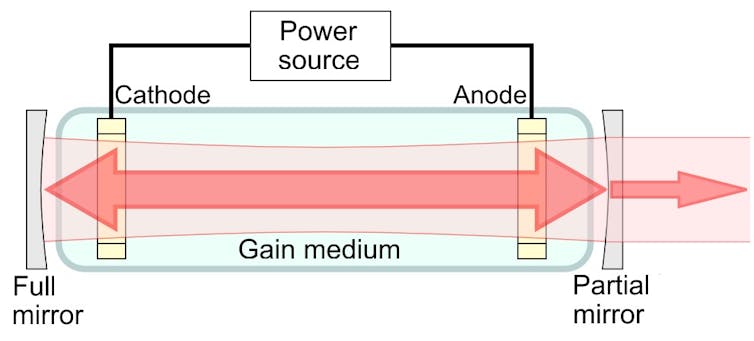

A laser uses electricity to generate photons, or light particles. The photons pass through a gain medium, a material that creates a cascade of additional photons, which rapidly increases the number of photons. All these photons are then focused into a narrow beam by a beam director.

In the decades since the first laser was unveiled in 1960, engineers have developed a variety of lasers that generate photons at different wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, from infrared to ultraviolet. The high-energy laser systems that are finding military applications are based on solid-state lasers that use special crystals to convert the input electrical energy into photons. A key aspect of high-power solid-state lasers is that the photons are created in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum and so cannot be seen by the human eye.

When it interacts with a surface, a laser beam generates different effects based on its photon wavelength, the power in the beam and the material of the surface. Low-power lasers that generate photons in the visible part of the spectrum are useful as light sources for pointers and light shows at public events. These beams are of such low power that they simply reflect off a surface without damaging it.

Higher-power laser systems are used to cut through biological tissue in medical procedures. The highest-power lasers can heat, vaporize, melt and burn through many different materials and are used in industrial processes for welding and cutting.

In addition to the power level of the laser, the ability to deliver these various effects is determined by the distance between the laser and its target.

Laser weapons

Based in part on the progress made in high-power industrial lasers, militaries are finding an increasing number of uses for high-energy lasers. One key advantage for high-energy laser weapons is that they provide an “infinite magazine.” Unlike traditional weapons such as guns and cannons that have a finite amount of ammunition, a high-energy laser can keep firing as long as it has electrical power.

The U.S. Army is deploying a truck-based high-energy laser to shoot down a range of targets, including drones, helicopters, mortar shells and rockets. The 50-kilowatt laser is mounted on the Stryker infantry fighting vehicle, and the Army deployed four of the systems for battlefield testing in the Middle East in February 2024.

The U.S. Navy has deployed a ship-based high-energy laser to defend against small and fast-moving ocean surface vessels as well as missiles and drones. The Navy installed a 60-kilowatt laser weapon on the destroyer the USS Preble in August 2022.

The Air Force is developing high-energy lasers on aircraft for defensive and offensive missions. In 2010, the Air Force tested a megawatt laser mounted on a modified Boeing 747, hitting a ballistic missile as it was being launched. The Air Force is currently working on a smaller weapon system for fighter aircraft.

Russia appears to be developing a ground-based high-energy laser to “blind” their adversaries’ satellites.

Limitations of laser weapons

One key challenge for militaries using high-energy lasers is the high levels of power needed to create useful effects from afar. Unlike an industrial laser that may be just a few inches from its target, military operations involve significantly larger distances. To defend against an incoming threat, such as a mortar shell or a small boat, laser weapons need to engage their targets before they can inflict any damage.

However, to burn through materials at safe distances requires tens to hundreds of kilowatts of power in the laser beam. The smallest prototype laser weapon draws 10 kilowatts of power, roughly equivalent to an electric car. The latest high-power laser weapon under development draws 300 kilowatts of power, enough to power 30 households. And because high-energy lasers are only 50% efficient at best, they generate a tremendous amount of waste heat that has to be managed.

This means high-energy lasers require extensive power generation and cooling infrastructure that places limits on the types of effects that can be generated from different military platforms. Army trucks and Air Force fighter jets have the least amount of space for high-energy laser weapons, and so these systems are limited to targets that require relatively low power, such as downing drones or disabling missiles. Ships and larger aircraft can accommodate larger high-energy lasers with the potential to burn holes in boats and ground vehicles. Permanent ground-based systems have the least constraints and therefore the highest power, making it potentially feasible to dazzle a distant satellite.

Another important limitation for platform-based high-energy laser weapons relates to the infinite magazine concept. Since the truck, ship or airplane must carry the power source for the laser, and that will limit the power source’s capacity, the lasers can only be used for a limited amount of time before they need to recharge their batteries.

There are also fundamental limits to high-energy laser weapons, including diminished effectiveness in rain, fog and smoke, which scatter laser beams. The laser beams also need to remain locked onto their targets for several seconds in order to inflict damage. Current prototype laser weapons are also proving a challenge to maintain in combat zones.

No fire from the skies

A new type of conspiracy theory has emerged in recent years claiming that nefarious entities have used airborne high-energy lasers to start wildfires in California, Hawaii and Texas. This is highly unlikely for several reasons.

First, the power level needed to ignite vegetation with a high-energy laser from the sky would require a large power source installed on a large aircraft. A plane that size would have been highly visible right before any fires were ignited. Second, in some images that claim to show the fires being started, the laser beams are green. Beams from high-energy lasers are invisible.

What comes next

In the future, high-energy laser weapons are likely to continue to evolve with increased power levels that will expand the range of targets they can be used against.

Emerging threats posed by low-cost, weaponized drones like those in use in conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine make it more likely that high-energy lasers will also find nonmilitary applications such as defending the public against terrorist attacks.