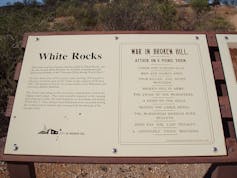

It’s another hot Australian New Year’s Day, and 1200 people are aboard a train bound for a picnic when a burst of gunfire shatters the festive atmosphere. Police return fire, killing the attackers – but not before four picnickers are killed and seven more wounded.

This is not a fantastic scenario: for several terrifying hours, this was Broken Hill in outback New South Wales on January 1, 1915.

A century on, religion is still being abused for political purposes by extremists. We have recently heard Islamic State (also known as IS or ISIS) calling on Muslims around the world to attack and “kill a disbelieving American or European … or an Australian or a Canadian or any other disbeliever from the disbelievers”.

Those recent pronouncements have some echoes of the now little-remembered 1915 Battle of Broken Hill. Similarly, the current delays in protecting civilians in Syria and Iraq from the horror unleashed by the IS – particularly the slow response of neighbouring countries like Turkey – mirror the situation in 1915.

Then, as now, the world was acutely aware of the humanitarian catastrophe that was unfolding in those same parts of the world. When unarmed civilians were trapped in the Hakkari Mountains or the city of Van, drastic action was required to save lives. Action that was too slow in coming for too many.

The question now is whether we learn from history, or sit back and watch more civilians die.

A call to action

The attack in outback New South Wales came only a few weeks after Sheikh-ul-Islam, the Ottoman Turkish Empire’s primary religious leader, declared a jihad (or holy war) on behalf of the government, urging his followers to take up arms against Great Britain and the Allies on November 14, 1914.

The sheikh’s declaration urged Muslims all over the world – including those living in Allied countries – to rise up and defend the Ottoman Empire. In part, his declaration read:

Of those who go to the Jihad for the sake of happiness and salvation of the believers in God’s victory, the lot of those who remain alive is felicity, while the rank of those who depart to the next world is martyrdom. In accordance with God’s beautiful promise, those who sacrifice their lives to give life to the truth will have honour in this world, and their latter end is paradise.

In modern parlance, Broken Hill could be classified as a “lone-wolf attack”. The attackers were former Afghan cameleers named Badsha Mohammed Gool, an ice-cream vendor, and Mullah Abdullah, a local imam and halal butcher.

While the attack was apparently politically inspired, the attackers confessed in notes they left behind that they were not involved in any organised group or militia.

Remembering the lessons of genocide

Now, just as in 1914, Yazidis, Christian Armenians and especially indigenous Christian Assyrians are being targeted in the name of Islam.

Just as it was in 1914, the 2000-year-old Christian presence in the Middle East is threatened with extinction, even as we approach the eve of the centenary of the 1915 Armenian and Assyrian genocides.

A century ago, the ideological forebears of IS targeted Christian Hellenes, Armenians and Assyrians. Once the people were largely gone, their physical heritage was targeted: churches, monasteries, schools, hospitals, community centres, homes. Thousands of Christian holy sites were systematically destroyed across Turkey, Iraq and Syria.

Just as before, religion is being abused for political purposes by groups of extremists. Late last month, IS destroyed the Armenian Church of the Holy Martyrs at Deir-e-Zor in north-eastern Syria, part of their campaign to “cleanse” their “caliphate” of the presence of “unbelievers”.

In a sea of inhumanity unleashed by IS, this was a particularly barbaric act, as the Church of the Holy Martyrs and its associated museum are dedicated to the victims of the Armenian Genocide.

The church served as a massive reliquary containing the bones of Christian Armenians deported by the Ottoman Turkish Empire to the desert wastes around Deir-e-Zor to die of hunger, dehydration or worse.

The sands in this corner of war-ravaged Syria contain dozens of mass graves from World War One, the victims of a systematic campaign of extermination by a government against its own citizens. The descendants of the survivors are now part of the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) militia of Kobanê, including units of indigenous Christian Assyrians who refuse to permit another genocide to occur.

Just as in 1915, while claiming to be unable to restrain the extremists who hide behind the veil of religion, over recent months the Turkish authorities have done little to help the international efforts to confront IS, while permitting IS fighters vital access across its borders with Syria and Iraq. This includes not doing enough to crack down on alleged IS oil smuggling.

Turkey still denies that it has allowed the oil smuggling. But in June, Turkish opposition MP Ali Ediboglu said that US$800 million worth of oil from IS-occupied areas of Syria and Iraq had been sold in Turkey. This equates to about US$1.2 million per day flowing into IS coffers, according to industry sources.

While Turkish MPs have just voted to allow NATO to use the 60-year-old Incirlik air base and potentially allow the Turkish military to enter Iraq and Syria to join the fight against IS, it’s still unclear exactly what action Turkey will take. Turkish Defence Minister Ismet Yilmaz has been reported as saying: “Don’t expect any immediate steps.”

Rescuing defenceless civilians

In World War One, small groups of specialist forces such as the Dunsterforce rescued tens of thousands of Yazidis, Christian Armenians and indigenous Christian Assyrians, placing themselves between the largely defenceless genocide survivors and those who would wipe them out.

The actions of men such as Stanley Savige (later Sir Stanley George Savige) should be a source of pride for all Australians: individuals standing up for what is right. Australia should draw inspiration from such men in the long fight against extremism that lies ahead.

There have been enough parallels with 1915. Time to break the cycle and save the fragments of Yazidi, Armenian and indigenous Assyrian civilisation that cling to existence in Iraq and Syria today.