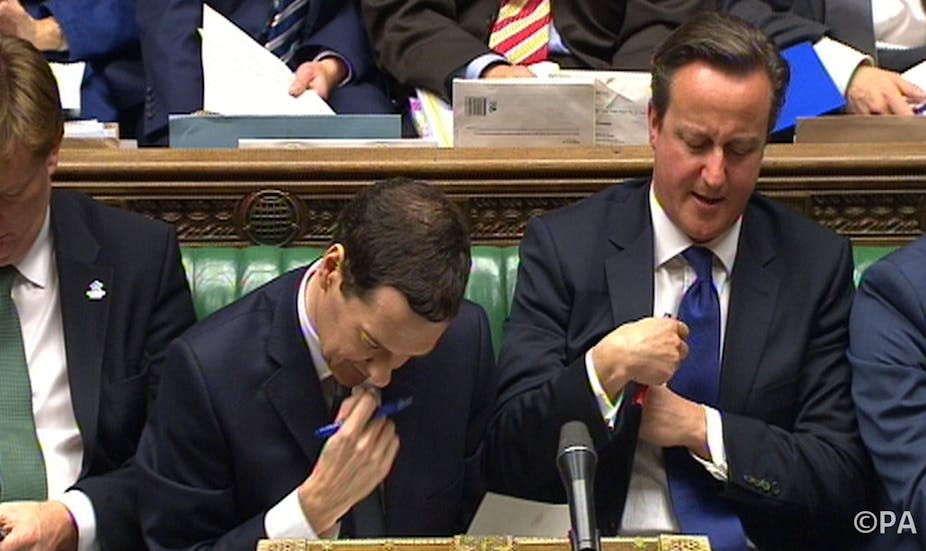

The Autumn Statement was supposed to be a celebratory moment for the coalition government – with its deficit-reduction strategy nearing completion and the 2015 election on the horizon, pre-election giveaways could begin. But, in his last update on the state of the UK economy, we find George Osborne in a highly defensive posture. And influential think-tanks such as the Resolution Foundation and the Social Market Foundation are now giving credence to the idea that the Liberal Democrats and the Labour Party may have more credible post-2015 deficit reduction strategies than a majority Conservative government.

The question of how we got here, despite the resumption of steady growth, seems to be genuinely puzzling Osborne and his hand-picked forecasters, based at the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). Our work at the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute examining OBR fiscal and economic forecasts since 2010, however, shows that the Conservative Party’s support for a services-led, low-wage recovery failed to make any meaningful progress on deficit reduction.

And the economic implications of the government’s recovery strategy were almost entirely missed by the government’s forecasters. This oversight has afforded Osborne a relatively easy ride until now, but today’s Autumn Statement surely represents crunch time for the coalition’s approach to reducing the deficit.

Why the targets are being missed

The headline is that the deficit-reduction targets will not be met. This failure will rightly form the basis of evaluations of the coalition’s record in office. And a look beyond the headlines reveals that targets are being missed as a result of the low-wage economy the present government’s policies have created. A failure to recognise this transformation has resulted in some seriously faulty economic forecasts.

The main, direct reason why the coalition’s deficit reduction agenda has failed so comprehensively is that tax revenues are significantly lower than expected. In 2013-2014, income tax revenue was £155 billion. Yet, at the 2010 Autumn Statement, the OBR forecast that income tax revenue (in cash terms) would be £178 billion (an over-forecast of 15%). The figure published today for 2013/14 revenue was actually slightly higher than predicted a year ago, but revenue has been significantly revised down, as usual, for every subsequent year.

Why, when unemployment has been falling so steadily, have income tax receipts been so sluggish? The answer to this question is fairly straightforward: more people are in work but earnings growth has essentially been stagnant for several years. This suggests a rise of a low-wage economy, where despite increasing employment opportunities, jobs are concentrated in low-wage and insecure services-sector industries.

Faulty forecasting

As late as his 2013 Autumn Statement, Osborne predicted average earnings growth of 3.3% in 2015, 3.5% in 2016, 3.7% in 2017 and 3.8% in 2018. Again, the majority of these figures have been downgraded significantly. For instance, next year earnings growth is now expected to be only 2%. We are witnessing a profound failure by political elites to acknowledge the transformation in the UK economy which has accelerated since the financial crisis.

The services sector has increased rapidly from three-quarters to four-fifths of the UK economy. This is a long-term meta-trend that the forecasters simply cannot compute. Much new employment is also in phony self-employment, with the self-employed now earning significantly less than they were before the crisis.

Much of the government’s rhetoric and austerity agenda, therefore, has been based upon notions that private sector employment will drive economic growth. But this is far harder when the economy is dominated by labour-intense industries which offer little scope for increases in productivity. Productivity forecasts have been consistently and significantly downgraded. This over-forecasting is more than merely unfortunate or embarrassing. It has convinced the government that a market-led recovery will (eventually) bear fruit, undermining the case for greater public investment to incentivise private investment.

The foreword to the coalition agreement in 2010 stated that “the deficit reduction programme takes precedence over any of the other measures in this agreement”. Eliminating the deficit, so we were told, was the key target to judge the government on.

Not only has the current government failed through its own definitions of economic priorities, but it has further generated a low-wage economy which has fatally undermined any possibility that meaningful progress on reducing the deficit might have been made. The emphasis it placed upon a private sector-led recovery diminishes with every downward revision made by Osborne and co, and consistent over-forecasting has both compounded and helped to obscure the problem.