In the modern era, hundreds of people climb Mount Everest each year, hauled to the summit by professional guides. This circus of commercial exploitation has robbed the mountain of much of its mystique. But the magic was still very much alive in the mid-20th century.

The Himalayan peaks were the final frontier of earthly exploration and interest in them was feverish – particularly among the British. Everest, the loftiest of all, was the ultimate trophy, literally and figuratively the pinnacle of human adventure.

My research using historical documents from the Royal Geographical Society, The National Archive and the British Library is shedding new light on just how obsessed British diplomats became with conquering Mount Everest in the early 20th century. It reveals how the British government threw money at the project to beat others to the summit and, having achieved the goal in 1953, went into diplomatic overdrive in the years after to make sure everyone knew of the nation’s success.

Although the men who first reached the summit were, by nationality a New Zealander and a Nepalese man, the expedition itself was organised by the British – a fact that they were extremely keen to emphasise. The arrival of Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay on Everest’s summit in May 1953 marked the culmination of over 30 years of British-led expeditions to conquer the world’s highest mountain. These ambitions were abetted throughout by officials in Whitehall and the Indian subcontinent in the hope of expediting a success that would burnish British prestige.

Britain’s foreign policy makers quickly spotted Everest’s potential as a soft-power tool. Writing in 1906, George Curzon, the Viceroy of India, worried about “alien hands” snatching the “prize” from Britain. By 1921, officials were referring to Everest’s conquest as a matter of “national importance”.

Henceforth the British state intervened systematically, lending British expeditions both diplomatic and material support. Officials machinated to secure British expeditions access to the mountain and, simultaneously, deny it to their rivals.

The British government subsidised food, transport and clothing and defrayed the salaries of climbers employed by the armed forces. It supported the design, testing and airlifting of equipment needed for high-altitude environments.

Getting our money’s worth

Coinciding felicitously with Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation day, news of Everest’s conquest thrust Britain into the international spotlight. And having expended considerable political and financial capital in helping the expeditions, the state craved a return on its investment once the summit had been reached.

To translate these events into a soft power resource, the Foreign Office immediately embarked on a campaign of public diplomacy. This sought to communicate not just with other governments but also to court the citizens of other states.

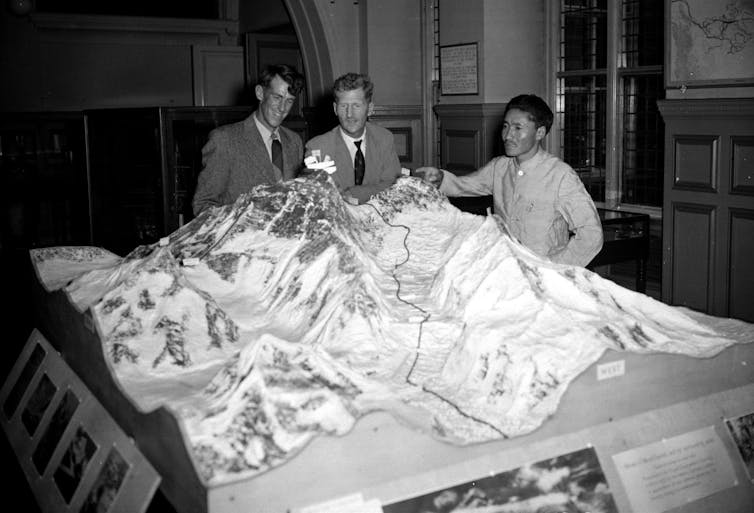

In a forerunner of today’s celebrity diplomacy, the Foreign Office used its diplomatic, financial and administrative muscle to facilitate more than 150 appearances by members of the climbing team throughout Europe, North America, Africa and Australasia. John Hunt, the expedition leader, was even sent to give a lecture in Moscow – a rare opportunity to project influence behind the Iron Curtain. The official expedition film was screened in coveted international locations and Everest exhibition sets toured the world under British Council auspices.

Government correspondence suggests this operation generated considerable goodwill and fortified Britain’s prestige internationally. But there were less positive consequences too. The soft power dividend was undermined by missteps that aggravated antipathy towards Britain. Officials could not police their celebrity diplomats at all times, which lead to gaffes. Some made bigoted comments about the sherpas, tainting the diplomacy project.

The inconsistent and contradictory images of Britain projected by its Everest emissaries was symptomatic of the geopolitical crossroads facing 1950s Britain.

Some used Everest to articulate a vision of Britain as an enlightened, forward looking, and technologically advanced nation still confident of its global role. Others painted it as a vindication of imperial values, an unattractive image for audiences that had, or wished to, cast off colonial oppressors.

The contemporary context for soft power differs drastically but, with Britain standing on the cusp of a new geopolitical inflection point, these issues still resonate.

Today’s debate is dogged by divisions among those who believe Britain’s soft power is best harnessed by communicating an image of an open, inclusive, outward-facing, free-trading global power and those inspired by a nostalgia for a golden age of empire. Just as in the 1950s, managing this tension is a central challenge confronting those responsible for Britain’s post-Brexit soft power strategy.