Attacks on international cargo ships in the Red Sea from Houthi-controlled Yemen have seen several cargo vessels hit by missiles and drones in recent days.

In response, global shipping companies and cargo owners – including some of the world’s largest container lines such as Maersk, as well as energy giant BP – have diverted ships from the Red Sea. So far, more than 40 container ships have been diverted, with many rerouted to less direct channels than the Suez Canal – an artificial waterway in Egypt that connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea.

Read more: US-led taskforce deploys in Red Sea as Middle East crisis threatens to escalate beyond Gaza

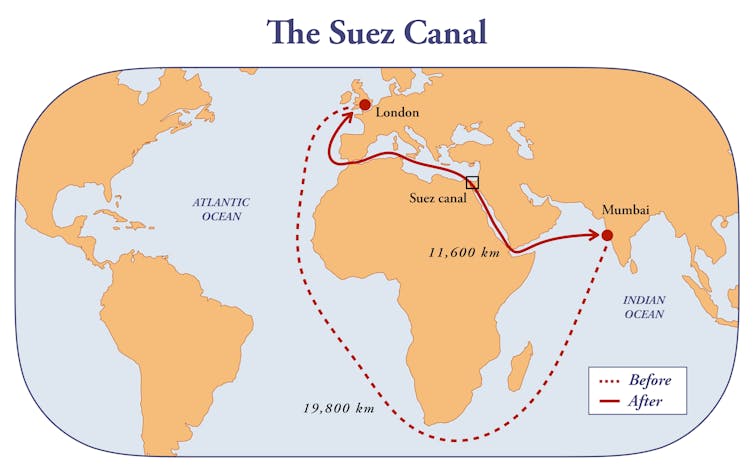

Opened in 1869, the Suez Canal is one of the busiest canals in the world, carrying around 12% of global trade. In 2022, 23,583 ships used this route. Any disruptions can have severe knock-on effects as these ships deliver goods from one country to another. Ultimately, this can even feed into the prices you pay for certain goods, as well as the time it takes to get things delivered from overseas.

Remember when the container vessel Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal for six days in 2021? It affected the shipping lane for weeks, playing havoc with global supply chains and disrupting global trade flow to the tune of billions. Previously, when the Suez Canal closed between 1967 and 1975 due to the six-day war between Israel and a group of Arab states, global trade was also negatively affected. Ships had to sale around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope instead – a much longer route.

While there is also a Northern Sea route that ships can take, it is not navigable in winter season and not yet commercially viable for many shipping companies. And so, the Suez Canal is the shortest and most suitable sea route between Asia and Europe.

Longer journeys will impact global supply chains

The sailing time between eastern Asia and western Europe can increase by about 25-35% when ships use the Cape route. For instance, a vessel travelling at 13.8 knots per hour (the current average speed of global container ships) between Shanghai, China and the Port of Felixstowe in the UK will see its sailing time increase from an average of 31 days to 41 days when sailing around the Cape.

It’s even worse for exporters shipping goods from say Italy to Dubai – the Cape route could take them 160% more time than the Suez route (12 days versus 32 days). These sailing times could be more for container vessels as they stop at other ports along their routes.

When it comes to comparing costs for the two routes though, the figures are not straight forward. Vessels passing through Suez Canal need to pay a toll. This can be as much as US$700,000 (£550,000) for a vessel carrying 20,000 containers (a typical large container vessel commonly used for east to west trades). But the Cape route could still cost 10% more, even with the canal transit fee, according to research published in 2022. The exact cost difference also depends on current fuel prices, as well as size and the type of vessel.

But it will be the reduced shipping capacity due to longer transit times, not the increased operating costs of shipowners, that will really weigh on global supply chains. This is because freight rates (the price companies pay to transport goods) depend on supply and demand.

It was a supply and demand imbalance that caused shipping costs to skyrocket during the COVID pandemic. Shipping supply was reduced because of disruptions, but demand increased because people were spending more on goods than services during lockdown. This time, the magnitude of freight rate increases is unlikely to be as large because there is no indication of a surge in demand for shipping services.

How shipping disruption affects you

If you live in the UK and have ordered new sofa from a manufacturer in China, you could expect a delay of at least ten days. The prices of certain products could also rise if freight levels increase significantly. An International Monetary Fund forecast shows a doubling of shipping costs could increase consumer price inflation by 0.7% percent.

However, sea freight activity generally has a marginal impact on most consumer prices – it only makes up 0.35% of prices for some types of clothing, for example. On the other hand, oil prices could spike if more energy companies follow BP and stop using Suez Canal, especially if this disruption persists over time. The price of Brent Crude – a global benchmark for oil – has already risen from US$73 on December 12 to about US$78 on December 18 2023.

Although you might not have to pay more for the products you buy, there is another cost of this situation, for people and the planet: increased carbon emissions. More than 3,000 extra nautical miles will be taken by vessels using Cape route, which could generate around 30-35% more carbon emissions than if these ships were sailing the Suez route. The shipping industry already creates 3% of global emissions.

Shipowners will be forced to keep diverting ships from the Red Sea if attacks on vessels continue. Of course, it remains to be seen when and how this problem will be solved. Until it is, uncertainty and change could continue to affect your pocket – and the planet.