Australian interests are intimately tied with those of Indonesia, and yet Australia continues to grapple with how to meet its needs for advanced level literacy in this relationship.

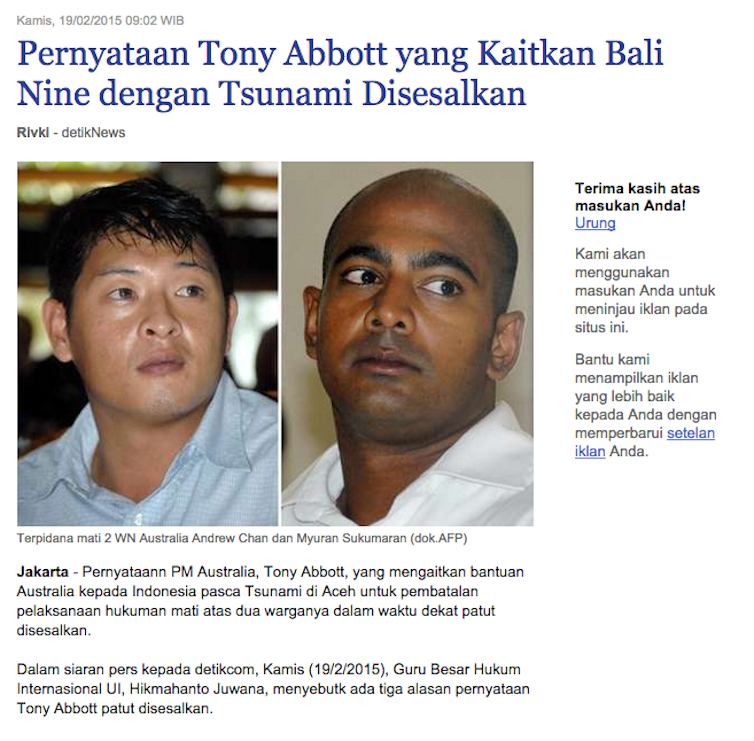

The most recent example is the flurry of diplomacy and media coverage in both Australia and Indonesia around Tony Abbott’s linking of humanitarian aid for victims of the 2004 tsunami and attempts to get clemency for two Australians on death row, Myuran Sukumaran and Andrew Chan.

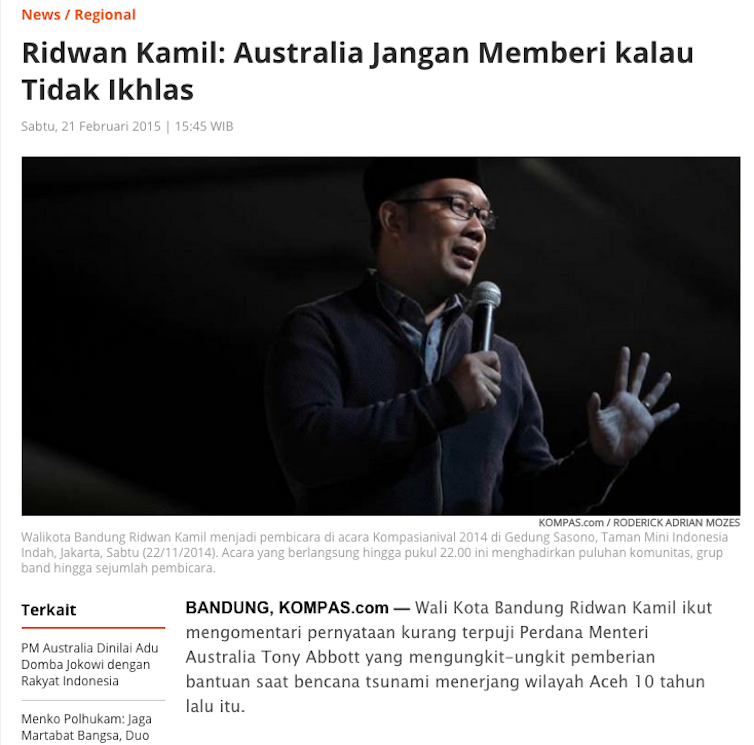

The #Coin4Australia Twitter campaign was launched in response to Abbott’s comments, urging everyday Indonesians to repay Australia for the aid the country had received.

I’d like to offer a way of understanding some of the issues exposed here by focusing on the meaning of bits of language in Indonesian society and the way they are interpreted. To do this I will focus on:

- a key word: ikhlas

- a compound: gotong-royong

- a phrase: minta maaf

Ikhlas

For many Indonesians, especially those brought up in a setting where many family, friends and neighbours are Muslims, the word ikhlas is pervasive. It is about the value of giving without expecting something in return in the material world.

The person giving does so with the hope that, when they die, Allah will look upon this type of behaviour favourably. It is sinful at worst, and very bad form at best, to remind someone of an ihklas gift that was given in the past.

City and country children will often attend informal religious school at the local mosque, where this value is taught before children are of primary-school age. This word and the values associated with it are endlessly repeated throughout one’s life in neighbourhood meetings, in Friday sermons, in weekly Qur'an recital and interpretation sessions, in the frequent sermons that are given in the evening during the fasting month and, much more commonly, in everyday conversations.

During my years in Indonesia conducting linguistic anthropological fieldwork I have regularly heard siblings and friends teasingly ask when offered a gift: “Ini ikhlas ya?” (“You’re giving me this freely without expecting me to give you something in return?)

It is thus no wonder multiple headlines appeared in the Indonesian press shortly after Tony Abbott’s comments that seemingly reminded Indonesians about a gift, in the form of humanitarian aid, that was originally interpreted as being ikhlas in 2004-2005. In short, it did not fit the model that many Indonesians are familiar with.

Minta maaf – asking for forgiveness

Yesterday the media reported that the prime minister had spoken with Indonesian President Joko Widodo about Chan and Sukumaran.

Without wishing to speculate, it is easy to imagine that the prime minister might have received some advice on the importance of minta maaf, "asking for forgiveness”.

Asking for forgiveness is another pervasive practice, at least in the areas of Indonesia with which I’m most familiar, Semarang in Central Java and Cirebon in West Java. Like ikhlas, minta maaf has its base in Islamic beliefs and is taught, modelled, and repeated throughout the lifespan in similar ways to ikhlas.

This idea goes something like this: everyone does the wrong thing every day, but you get plenty of chances to ask for forgiveness for your sins. You can pray five times a day, do extra prayers, give to the poor, do the fast, undertake the haj pilgrimage to Mecca, and so on.

At the end of the Ramadan the final act after morning prayer is to visit relatives and neighbours (in order of age and/ or status) and ask forgiveness for all the wrongs done, whether done on purpose or by mistake.

It is normal to give forgiveness and extremely bad form and a sin not to, even if asking and giving forgiveness relates to some truly horrible things. Recent reports in the Indonesian media seem to have interpreted the content of the prime minister’s recent phonecall as an apology for linking humanitarian aid with clemency, and this can only be a helpful development.

Gotong-royong

Being able to ask for forgiveness is part of being able to get along (gotong-royong). Again this value is taught in the family from a very early age, as pointed out by the anthropologist, Hildred Geertz in her 1961 book The Javanese Family.

Geertz writes about gotong-royong in terms of the Javanese term rukun, which has a similar meaning. Two long-term scholars of Indonesia, Shigeo Nishimura and Niels Mulder, have pointed out that from 1968 onwards these terms became part of the Indonesian education system through the citizenship education curriculum.

During my own fieldwork in the mid-1990s this concept was an extremely important part of everyday neighbourhood life in urban Indonesia. In the extremely diverse neighbourhood where I worked, new neighbours were constantly taught the value of getting along in neighbourhood meetings and in everyday conversation.

Again, if we can assume Abbott’s phonecall will continue to be interpreted as a call for forgiveness, this can only be good in terms of relations between the two countries.

What happens now?

Indonesia is extremely diverse and thus the understandings I have tried to sketch here won’t apply across Indonesia. In addition, there are issues over and above linguistics to consider presently.

Professor Tim Lindsey’s recent Conversation article on Indonesian domestic politics and how it relates to the ongoing discussions over clemency for the two Australian inmates facing imminent execution makes a very strong point:

the basic problem for Jokowi [President Joko Widodo] is that he seems stuck with two inconsistent populist policies. He is committed to the executions as a “shock therapy” solution to what he says is a rising drugs “emergency”, while promising to continue saving Indonesian offenders facing death overseas.

And, in the same article:

Despite the obvious contradictions in his position, Jokowi is unlikely to be willing – or politically able – to abolish the death penalty now.

Like many others, I can only hope this prediction proves wrong.