Despite the recent admission by the US president, Joe Biden, that the joint US-UK campaign of airstrikes against Iran-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen was not working, the two allies conducted their eighth round of bombardment against Houthi positions on January 22. A spokesman for the UK prime minister, Rishi Sunak, told journalists that the military action was accompanied by diplomacy aimed at “putting diplomatic pressure on Iran to cease their support of Houthi activity”.

The US-UK bombing campaign has come in response to repeated Houthi attacks on vessels in the Red Sea, which they claim aims to target Israeli vessels or sea traffic bound for Israel, in response to the Israeli military action against Hamas in Gaza.

All this comes at a precarious moment for the region. Hezbollah, the Lebanese “Party of God”, is increasing its presence on Lebanon’s southern border with Israel. Jordan has carried out airstrikes against suspected drug dealers in Syria. Tensions in Balochistan – on the border of Iran and Pakistan – are escalating. Iran and its allies in Iraq and Syria continue regular attacks against US bases in the region. And the relentless Israeli assault on Hamas in Gaza continues, at a massive cost – mainly to Palestinian civilians.

While some may look at the Middle East and reject any semblance of order in the region, the reality is rather different. Although the region has endured a tumultuous two decades since the 9/11 attacks on New York sparked the US-led “War on Terror” and the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, the underlying structures that regulate life largely remain in place. Broadly speaking, sovereign states remain intact – albeit with challenges to the territorial sovereignty of Iraq and Yemen – along with a strong authoritarian current, powerful armies, and the role of the US in the region.

October 7 changes the picture

Things have come a long way since the beginning of 2023, which had offered much hope for the gradual improvement of regional security. The year began with a normalisation agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran while, thanks to the signing of the Abraham Accords in 2020, there was also the prospect of normalisation of relations between the Saudis and the Israelis. The kingdom appeared to be keen to follow neighbours Bahrain and the UAE in establishing relations with Israel for the first time.

Meanwhile, continuing peace talks between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis gave hope of an end to the long civil war in Yemen. As a result, there was reason to (tentatively at least) hope for a new era of regional politics, driven by economic interests.

All that changed with the October 7 Hamas attacks in Israel and the Israeli response in Gaza, which appear – for now at least – to have scuppered any hope for warming relations between Israel and the Arab nations.

The ‘axis of resistance’

Iran’s regional relations

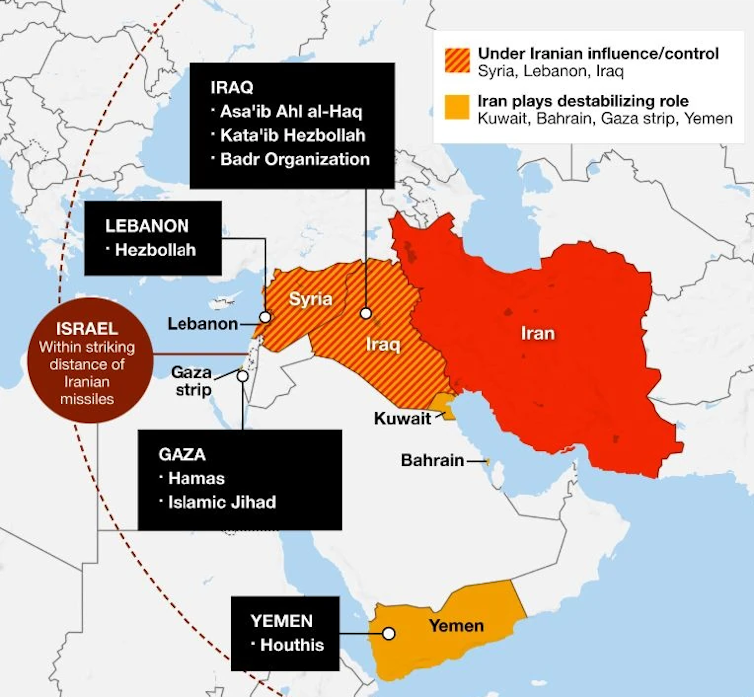

Unlike its Arab neighbours, the Islamic Republic of Iran has long articulated support for the Palestinian cause, drawing on ideas of martyrdom and resistance found within Shia Islam – of which Iran has long aimed to be recognised as the ideological head – to support this position. This ideological approach has helped Tehran cultivate relations with groups across the region who position themselves against Israel and the US.

The axis is directly at odds with the dominant ordering principles of Middle East politics. It operates as a transnational collective of violent non-state actors opposed to the US, Israel, and those Sunni Arab states who have relations with Washington and normalised with Israel.

Over the past two decades, Arab leaders have framed Iran as a malign actor in the Middle East, seeking to destabilise the region in pursuit of its own goals. Iran is positioned as nefarious puppetmaster, the patron of a proxy network whose constituent parts do its bidding.

The reality, however, is more complex. A closer look at the relationship between Iran and the Houthis reveals this complexity. Unlike Hezbollah, which was formed under direction from Iran in the early 1980s, the Houthi movement emerged as a result of sectarian conflict. Yemen’s Houthis come from a strong Zaydi tradition in north Yemen, which placed them in direct conflict with Saudi-backed Salafis who dominated the (internationally recognised) national government.

It is generally accepted that the Houthis procured weapons from Yemeni sources until the late 2000s, when Iran sensed an opportunity to increase its influence on the region at relatively little cost.

But since then, tensions between the Houthis and Iran have appeared around ethnic, linguistic and doctrinal differences. While both are Shia, the Houthis are Zaydi and Iran is Twelver. The difference, while subtle, is significant. While Iran has been a source of inspiration (and funding) to Houthi leaders, Zaydis do not follow ayatollahs for theological or political guidance. Significantly, they are also not beholden to Tehran for every move they make.

Much like with Iran’s relationship with Hezbollah, there are numerous instances of friction between the Houthis and the Islamic Republic, stemming from ethnic tensions, sectarian schisms and geopolitical aspirations.

Iranian pragmatism

It’s also important to realise that despite appearances and the way it is often portrayed in the west, Iran is a deeply pragmatic state, as shown in its attempts to normalise relations with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states in recent years. So, while Tehran and its allies have engaged in low-level skirmishes with the US and Israel, it has been careful to keep these acts of violence below a threshold that might lead to escalation.

That said, there’s no doubt this is a very dangerous time in the Middle East. As the situation in Gaza and the Red Sea deteriorates and against the backdrop of continuing skirmishes between the Israel Defense Forces and Hezbollah in Lebanon, the sheer number of moving parts in this picture means that the situation could easily spiral out of everyone’s control.

As recent history has shown us, despite the myriad challenges and spoilers on all sides, diplomacy can work. Now, more than ever, it must be given a chance.