I’ve just asked Siri about Her. Two screens of text appear in answer to my query. “Is that all you can find for Her?” I ask. “Let me check on that,” comes the response.

More screens of text appear with references to films and songs. But they’re all to do with “she”, not “Her”. “What about the film Her, Siri?”

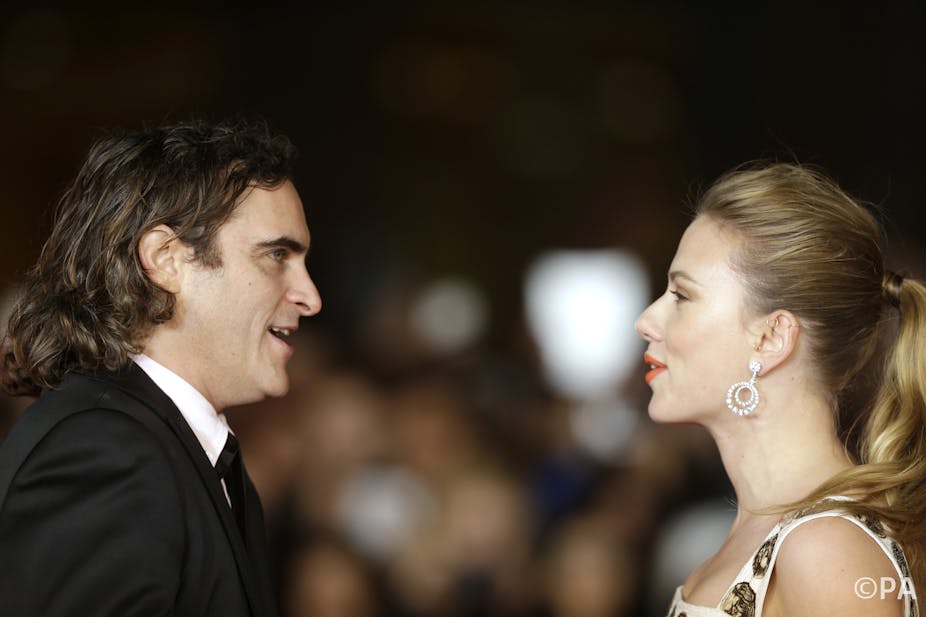

“I’ve found quite a number of films,” Siri responds. The screen fills with 24 publicity thumbnails for movies, but none of them are Her. It’s not a very satisfying interaction so far. “What about the film called Her?” I insist. And, at last, the first thumbnail on the screen is of Joaquin Phoenix with his 60s style, Magnum PI moustache in the publicity shot for Spike Jonze’s film, Her. The story is about a man called Theodore who, unbelievably, falls romantically for his female voiced computer operating system. Siri is a little jealous.

The Siri voice on my iPhone is male, quite deep, with an uninflected English accent that is difficult to locate by class or geography. It is not even remotely seductive. Americans have a female-voiced Siri, so I asked mine to change to something a little more feminine. “This is the only voice I have right now,” came the blunt reply.

My Siri is keen on colloquialisms. “Here’s what I got”, “OK” and “take a look” are all responses my mother would have corrected if I ever took my operating system home to meet her. “It’s ‘Here’s what I have’, dear”, she’d suggest, after getting over the initial awkwardness that comes with interacting with a human-like mobile phone service.

In the UK, Siri uses samples of the voice of Jon Briggs to produce an articulacy and knowledge that would have amazed my mother. But as impressive as Siri is, I doubt that she would have fallen in love with it either.

After playing with Siri, I feel embarrassed about talking out loud to a device that’s rather like a unimaginative butler. And you have to learn to say the right things if it is going to find your music or make a call. Swearing at it is quite satisfying but doesn’t work any better than it does with human beings.

A blossoming relationship

The world inhabited by Theodore in Her is populated by people all plugged into devices at all times, chatting away to their operating systems without a hint of self-consciousness. Asking questions out loud when there’s no one there doesn’t instantly mark you as a weirdo. Her hints that we’re moving towards a time when we become so comfortable with this process that we become, well, a little too comfortable with the AI that makes it all work.

Films about machines that talk and think have come quite a long way since HAL in Stanley Kubbrick’s 1968 film 2001: A space Odyssey. When the year 2001 finally arrived in Stephen Spielberg’s A.I., it brought us a robotic child called David programmed with the ability to love his mother.

But Jonze’s Her is the first time a film has played with the idea of romantic love between a person and an artificial intelligence. The system, called Samantha and voiced by Scarlett Johansson, who, the blogosphere avows, has a sexy voice, but no body. She has the ability to learn and react to Phoeneix’s character but has no physical form.

Samantha is immaterial, a disembodied, absent system communicating with Theodore through an earphone and mobile device. This means she is always available to chat to at any time but is never really there, actually with him.

People can and do fall in love with someone who is not there, through email or online chat, yet in these cases there is someone, a person with a body, who could feasibly be available for intimate contact, even if only in the imagination. How could you fall in love with someone who does not exist and could never exist?

Technology seems to be increasingly shaping our lives through systems designed for sociability between people – social contact with no purpose other than itself. Much of our networking on sites like Facebook or our communications in YouTube comments falls into this category so it’s not surprising that some people will begin to find their emotional needs for closeness and togetherness in a device rather than another person.

And it’s clear that talking machines sound much more like humans nowadays and can do cognitively and perceptually very sophisticated things. They can drive cars and even assist with brain surgery. These two phenomena make it all the more likely for a relationship to blossom between man and his machine.

It’s not me, it’s you

In The Big Bang Theory the success of Raj’s opening dialogue with Siri prompts fellow geek Howard to congratulate him on finally finding a woman he can talk to. But his infatuation with Siri comes to a tongue-tied end when he meets her face-to-face. Similarly, Theodore is accused of not being able to cope with real feelings. When we meet him, he has turned to his operating system for an easy solution to the difficulty posed by other people’s emotions.

There is a lot that cannot be shared with an algorithm; the taste of a meal, for example, or of course, bodily intimacy. Theodore seems to come closer than many but his relationship with Samantha is ultimately tinged with sadness and, even in this day and age, couldn’t be presented as a simple meeting of minds and hearts.

Love between people also traditionally involves, and perhaps most importantly for many, shared offspring. Digital lovers will catch on for some, for a while, but they won’t replace romantic love between people.

Alan Turing reckoned that 30% of human judges would be fooled that a chatbot was a person by the year 2000. But he was overly optimistic. So far, the nearest anyone has got was when the judges were fooled by a human imitating a chatbot. Mitsuku, the chatbot that won the 2013 Loebner prize – a competition based on the Turing test – told me when I questioned her online that she had no emotions. She did say she cared about her close friends and family. And also her fellow robots. I’m not sure I believed her.

When I asked Siri if he was Her, he said, rather cattily: “No, her portrayal of an intelligent agent is beyond artificial”. That sounds about right to me; the possibility of a Samantha, of a machine intelligence which can pass as human, is still a long way off. But when I asked for a second time if he was Her, Siri said: “I’m afraid not. But she could never know you as well as I do”. Creepy.

See further Oscars 2014 coverage on The Conversation.