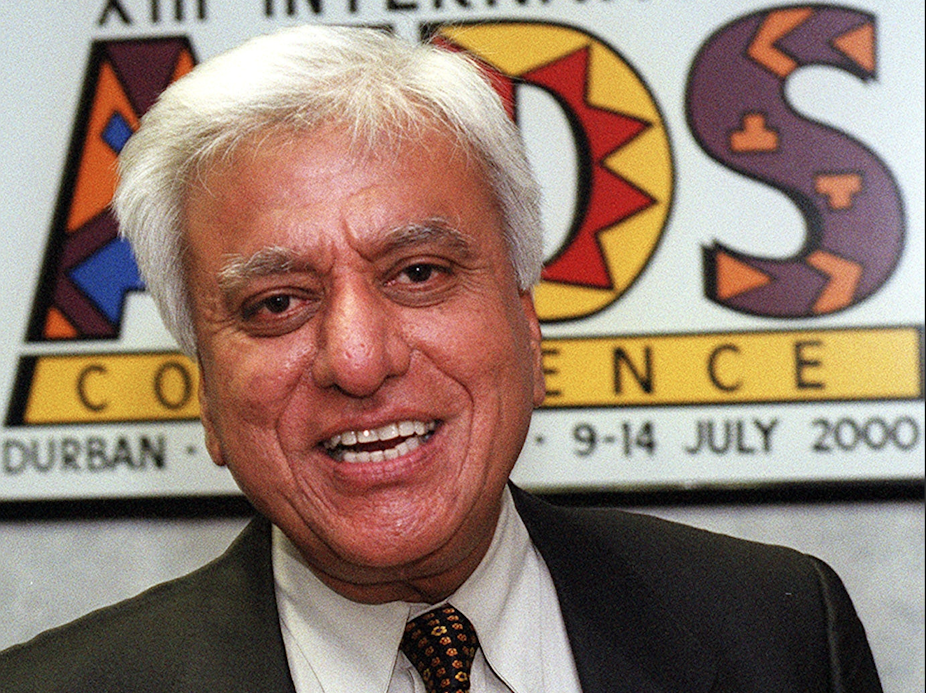

South African-born Professor Hoosen “Jerry” Coovadia, renowned academic and prominent anti-apartheid activist, passed away on 4 October. As a paediatrician I was privileged to know and work with him over two decades. Prior to that I knew him when we were both health activists in apartheid South Africa.

In 2019 Coovadia was profiled in the leading health academic journal, The Lancet, as an icon in South African health. The profile described him as the “Nelson Mandela of health”. This was in tribute to his dedication to ameliorating the diseases that afflicted children of South Africa, like malnutrition, measles and HIV, and his role in health activism.

In 2014, in my capacity as the president of the South African Medical Research Council, I was honoured to award him the SAMRC Presidential Award in recognition of his life-long work in child health, his impact in the area of preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the huge influence he had on health in South Africa.

Jerry was pivotal in proposing the use of maternal antiretroviral therapy to prevent breast milk transmission, which has now become the norm at a global level. His role in research that led to the control of HIV infection in children was so great that, in my view, it cannot be quantified in any meaningful way.

Who was Jerry Coovadia?

Jerry was born in Durban, on the east coast of South Africa, in 1940.

He knew instinctively from a young age that he would become a doctor. He did some of his medical training in India, and then returned to South Africa, where he was exposed to the atrocities of a two-tiered health system under which black South Africans bore the brunt of poor healthcare.

As a paediatrician, he excelled academically, training in immunology and eventually heading the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health at the University of Natal.

During his time as an academician he became prominent in the anti-apartheid movement.

The AIDS fight

I began working with Jerry in the mid 1990s. His path and mine would intertwine over the next 20 years as we bore witness to the explosion of HIV in children. He was working at the King Edward Hospital in KwaZulu-Natal while I was at the Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital in Soweto.

Over the next decade we would “cross horns” on the various interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

We didn’t always agree on interventions to prevent post-partum transmission through breastfeeding.

Even though our strategies differed, we were completely aligned in our common goal of trying to mitigate the scourge of HIV in the children we were trained to care for.

His textbook Paediatrics and Child Health was my Bible. My colleagues and I revered him as the doyen of child health in South Africa.

It was a huge privilege to collaborate with him on research to deliver antiretroviral therapy as an intervention to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

We worked together on studies seeking the most cost-effective way of preventing paediatric HIV using the least amounts of antiretrovirals at a time when these were prohibitively expensive. The two biggest were the PETRA study, evaluating various short courses of AZT and 3TC to interrupt perinatal transmission, and the SAINT trial, which evaluated the role of Nevirapine for preventing mother-to-child transmission.

Over the years, we would co-publish on these studies and the effect of these various interventions to minimise breast milk transmission.

Activist years

Before I worked with Jerry as a young doctor, we were both health activists. I belonged to the Health Workers Association, which later became the South African Health Workers Congress; he was a member of the National Medical and Dental Association and was a leader in the talks to merge these two organisations.

I appreciated his activism and his vision for an equitable health system which he channelled into his work as a paediatrician and his work as a scientist.

He demonstrated to us as young doctors the role of social activism in health and that ill health is inextricably linked to socio-economic and political factors. If we were to be meaningful in our role as doctors, we had to address these factors with the same vigour as we demonstrated in the wards where we treated sick children.

Jerry encompassed what it means to be a doctor. He always lived by the Hippocratic Oath, basing his practice in medicine on the principles of beneficence, non-maleficence, justice and respect.

I am deeply grateful to have brushed shoulders with this great man. Go well Jerry, a life well lived, and many thanks to your family for sharing you with us.