Dutch professor of medicine Joep Lange and his partner Jacqueline van Tongeren were among the 298 people who perished in Malaysia Airlines flight 17 after it was struck down on the Russian-Ukraine border last night.

Lange was on route to Melbourne for the 20th International AIDS Conference, which starts on Sunday.

Professor Lange’s friend and colleague David Cooper reflects on their work together and Lange’s legacy.

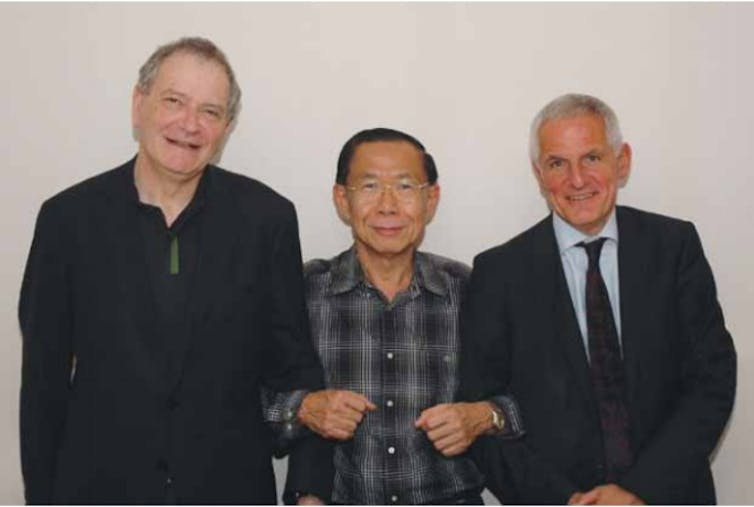

Large international meetings, such as AIDS2014, are the ideal venues for colleagues and collaborators to get together and swap ideas. During the early 1990s, I often met up with two old friends and colleagues, Professor Joep Lange, my counterpart at the National AIDS Therapy Evaluation Center (NATEC) in Amsterdam, and Professor Praphan Phanuphak, head of the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre (TRC-ARC) in Bangkok.

We were aware of the difficulty at that time in convincing pharmaceutical companies and other collaborators to support HIV-related clinical research in areas where HIV is most prevalent: low- to middle-income countries. These countries lacked the resources to pay for expensive treatments, as well as the consistently high-level expertise to achieve scientifically rigorous outcomes.

In November 1995, we three researchers agreed on the need for a multi-centre clinical trials organisation in Thailand, which had the additional benefits of a supportive government and a quality health system. The Netherlands-Australia-Thailand Research Collaboration, known as HIV-NAT, had begun, and soon became a model for HIV clinical research in developing countries.

HIV-NAT’s first research study, of 75 participants, started in September 1996. It was a study of the feasibility of dose reduction of two key antiretroviral therapies in combination, because of the lower average body weight of Thais. This pioneering study led to the notion of treatment optimisation to reduce costs of antiretroviral drugs.

Joep and I then lobbied the pharmaceutical industries to move their research efforts to Thailand, while Praphan brought on board the support of the Thai Ministry of Public Health. Experienced clinical trials physicians and biostatisticians from the Netherlands and Australia spent time up-skilling Thai health care workers in all aspects of clinical research.

The group’s first two studies at Chulalongkorn Hospital in Bangkok helped establish a future teaching model for sites around Thailand and the region. These two studies were pivotal to the future success of HIV-NAT, which has become a powerhouse of internationally recognised HIV research.

Another organisation Joep founded, PharmAccess Foundation, was among the first to initiate HIV treatment programs in sub-Saharan Africa. In turn, PharmAccess created the Health Insurance Fund, which gives subsidised health insurance to more than 100,000 people in Nigeria, Tanzania and Kenya.

PharmAccess also created the Medical Credit Fund, which enables loans to private basic health care providers to provide better care, SafeCare, which supports basic health care providers to upgrade, and the Investment Fund for Health Care in Africa, which invests in health care strengthening.

Sadly these days the roll-out of therapy has stalled through lack of international funding. We desperately need to double the number of people on treatment to bring the epidemic under control. What a great legacy it would be to his work if we could achieve that.

On a personal note, Joep was a great reader; he always had a book in his hands and was very quickly across anything new. He loved quirky writing and particularly loved the Portuguese Nobel laureate in literature, Jose Saramago.

He was also an art hound. He once took me to the modern art museum in Amsterdam, the Stedelijk, where he loved the Maleviches (Cubist art in the Russian tradition) and their commentary on life in communist Russia.

Joep was the very first person to say that if you could get a cold Coke in any village anywhere in sub Saharan Africa, there was no reason why you couldn’t distribute antiretroviral therapy to everyone who needed it.

He had been amazingly effective at recruiting Dutch socially responsible companies such as Royal Dutch Shell and Heineken to fund his work, setting up pilot programs to get people onto treatment in low and middle income countries. His ideas were always ahead of his time.

I am privileged to have been Joep’s colleague for more than two decades. His contribution to HIV research and treatment, and his determination to ensure access to those treatments for people in Africa and Asia, cannot be underestimated.

Joep was a special person, a brave researcher, an invaluable collaborator, a great friend and colleague, and an international figure. Joep’s partner Jacqueline van Tongeren died with him on flight MH17. He leaves behind four daughters and a son. We are all the poorer for his loss.