The Redfern Park Speech, given by former Australian prime minister Paul Keating on December 10 1992, was a speech worth fighting for. It captured harsh truths about Australian history; it used those as a basis for building trust with Indigenous Australians; and it marked a turning-point for non-Indigenous understandings about Aboriginal reconciliation.

But a particular line of interest in the speech is the tension that has arisen between Keating and his former speechwriter Don Watson. This tension essentially dates to the publication of Watson’s memoir Recollections of a Bleeding Heart (discussed below).

Thinking about the dispute with reference to the manuscript – which I have been researching for a longer article in Overland – is an opportunity to reflect on the speech itself. It points to reasons why Watson and Keating have something worth arguing about – why the speech has acquired such lasting resonance in a country that often prefers to forget.

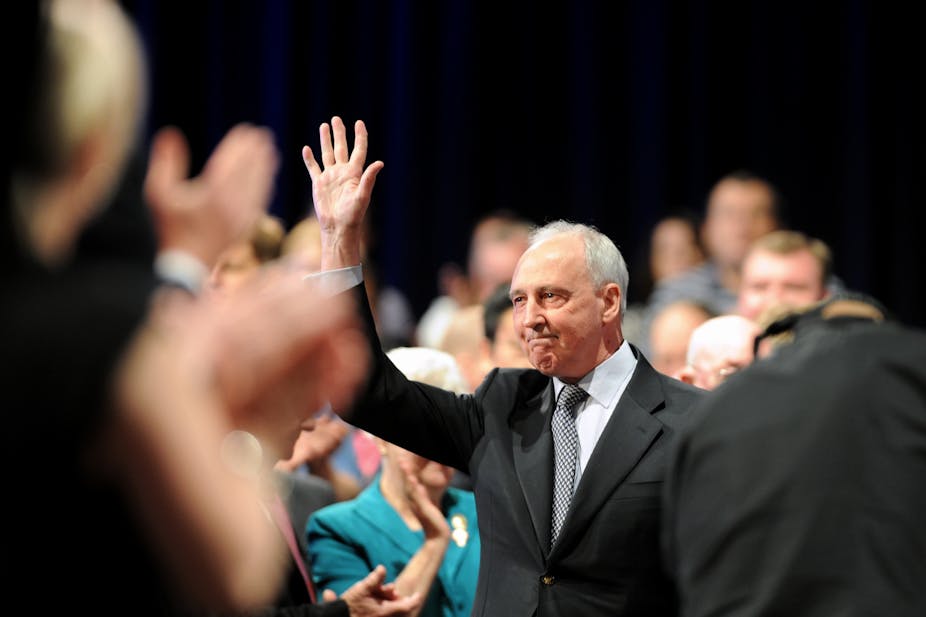

Keating proclaimed the Redfern Park Speech just over a year into his term as prime minister. He chose to do it in the inner-city Sydney suburb of Redfern, which for decades had been the focal point for Aboriginal cultures in Australia’s largest city.

As you might sense from audio and video (see videos below) of the speech, it was a rowdy audience.

Keating was speaking to the converted in one sense, but in another sense he was speaking to a certain unconvertible contingent – some of the Koori locals, whose experience was so bitter that nothing a white prime minister said could mollify them.

As he tried to, though, Keating named the parties to Aboriginal reconciliation in a way that has characterised the grammar of non-Indigenous discussion of it – by supporters, sceptics and apathetic citizens alike – ever since:

1) a “we” that incorporates all non-Indigenous citizens, no matter how recent or ancient their family histories of immigration to Australia.

2) a “they” that incorporates all Indigenous Australians.

In Australia’s public discourse since 1992, to switch pronouns and their entailments away from this frame of reference effectively signals a move away from discussing reconciliation as such.

The video recordings of this speech remind us that Keating’s performance was strikingly “writerly,” rather than performed for charismatic effect. That marks a significant contrast with his fluency, command, and sheer destructive glee as an improvising speaker – an aspect the recent Kerry O’Brien interview series brought out strongly.

When we look at the manuscript below, we see a document that Watson typed and printed out for the prime minister in landscape-oriented pages, using large type, sans serif, line-and-a-half spaced.

Numbers 1-22 are handwritten near the top of each page. The same hand, Keating’s, has scrawled changes to very few words.

Much more common, though, are annotations that mark up timing, emphasis, and phrase coherence. These non-verbal annotations show a speaker striving to interpret and make the most of his manuscript before delivery, but not so much to edit and alter it.

They are the sorts of annotations a musician might make in preparing a score. They suggest a powerful sense of fidelity to the manuscript.

In 2002 Watson published Recollections of a Bleeding Heart, an insider memoir on the running and then the decline and fall of Keating’s government. It offers a fairly detailed historical background to this manuscript.

Keating’s response to the book was hot anger. He quoted the Australian Labor Party’s most revered speechwriter, Graham Freudenberg, who he claims remarked to him: “Broke the contract mate.”

This Freudenberg quotation itself is of uncertain value as evidence. Whatever its status, Keating uses it to suggest either that former political staff should not reveal anything their former employers do not permit. That is, the ethical and professional compact should outlast the defined terms of the contract of employment.

Watson’s essential counterclaim seems to be that he still is a writer — of books. When he stops writing for someone in particular, he still keeps on writing.

But the sharpest point of Keating’s complaint was an intellectual property dispute. He insisted:

Watson was not the author of the [Redfern Park] speech. The sentiments of the speech, that is, the core of its authority and authorship, were mine.

So does that make Keating the author? Joel Deane and others agreed with this line, arguing the first rule of speechwriting is that “the words aren’t yours”.

Complicating the situation, Watson had already pleaded no contest. Prefacing a published collection of transcripts that includes this speech, Watson set out a very minimalist ethics of speechwriting:

There are no rules or guidelines, except the unwritten one: ownership resides in the speaker.

But is the speech’s authorship in that sense really the contest here? It seems that we have a contest about the wordsmithing, about the creative work.

As a study in rhetoric, the most interesting aspect of Keating’s remarks is the assertion that he was an integral part of the drafting team. He wants to be known as a fellow-techie, not merely some benign director who fed the running briefs to his staff – and certainly more than a show-pony performing the scripted lines.

There must be at least some truth to this view. To think it even matters, though, reveals how assumptions about creativity and conceptual design in political speeches rest with the writer not the performer.

Against such assumptions, speechwriters have traditionally received little attention from political history.

Ultimately, there is not enough evidence, nor any particular need, to find one or other party conclusively right or wrong on this matter of Keating versus Watson. The very existence of the dispute tells us more than its adjudication is ever likely to.

People who remember Keating fondly often cite his employment of Watson as evidence for their attitude. People who admire Watson generally count his work in Paul Keating’s office as evidence for theirs.

This speech typically features somewhere near the top of the list in both conversations.