Assassination has never changed the history of the world.

The speaker was Benjamin Disraeli; the occasion, his address to parliament following the murder of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth in 1865.

Disraeli’s speech referenced Lincoln the private man over the Lincoln the statesmen, whose final hours were “homely” and “innocent,” befitting the popular image of the president known as Honest Abe. In so doing, Disraeli drew attention to the conundrum at the heart of assassination plots throughout history: to what extent, if any, does the individual statesmen represent the state?

The “costly sacrifices” and “violent deaths” of Caesar, Henri IV of France or William the Silent, the first head of state to be killed with a handgun, did not, Disraeli claimed, stop “the inevitable destiny of his country.”

Disraeli’s comment recalls the medieval concept of the king’s two bodies, in which the king’s corporeal body and the body politic exist as two separate entities: the monarch, essentially, is not the monarchy. “The King is dead! Long Live the King!” recognises the passing of the former whilst heralding the inexorability of the latter. According to this model it takes revolution, not assassination, to end a regime.

And yet assassination has been used as a political weapon since earliest times. Although the court tasters of old have been replaced with armed bodyguards and secret servicemen, the peril inherent in being a head of state has not gone away. From the removal of tyrants as a form of political succession in classical civilisation to the state-sanctioned “decapitation strikes” of the present day, the method and motivation may have changed, but assassination as political tactic remains a constant.

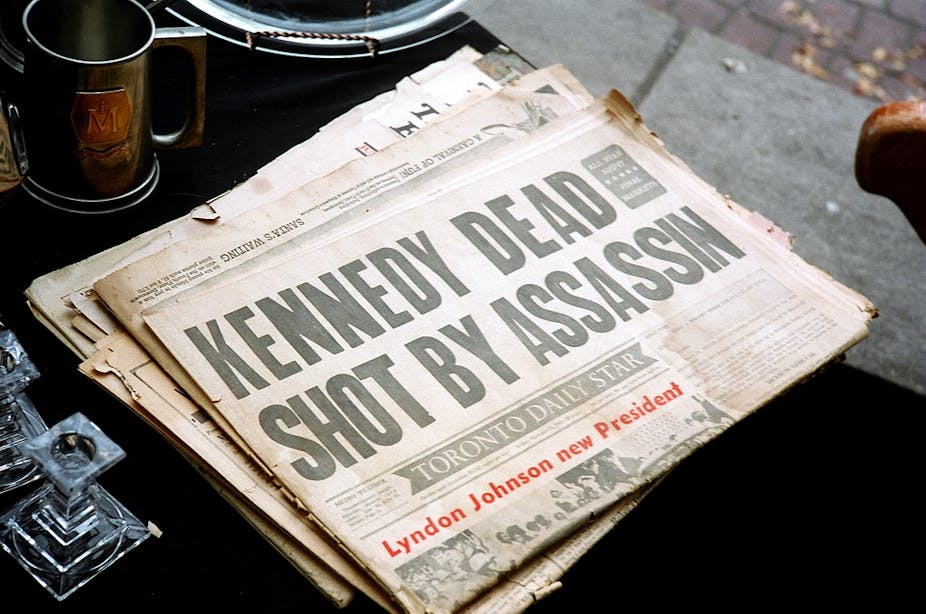

In the United States, Lincoln’s death was the first in a long history of assassination attempts against US presidents. Since the assassination of John F Kennedy in 1963, every US president except Johnson has had at least one attempt made on his life and the archetype of the “lone gunman” continues to haunt the American popular imagination, representing the dark side of the individualist frontier spirit and the right to bear arms.

The archetype of the assassin has undergone various permutations too, from naive idealist to principled political actor or unhinged anarchist; from hitman to religious fanatic. Their motivations, similarly, are various: political conviction, a desire to change history, power, money, or more recently, a quest for notoriety. That an ordinary individual, a little nobody, could fell the most powerful heads of state has haunted the imagination throughout history.

The original assassins, the 11th-century Hashishin who struck terror in the hearts of the Crusaders, were mythologised by Marco Polo as silent, ruthless killers who struck with almost supernatural speed. They, at least, were worthy, if terrifying, opponents. Henri IV’s assassin in 1610, on the other hand, the delusional and pitiful Ravaillac, stabbed the king in his own carriage in broad daylight and waited to be arrested. It was inconceivable to contemporaries that this pathetic, broken figure, whose public execution was orchestrated for “his soul to trickle away drop by drop” for maximum suffering, could have killed the beloved Henri.

Conspiracy theories

When torture did not result in confession about a larger conspiracy, the authorities concluded that Ravaillac must be under the influence of witchcraft. Further back still, Classical historians such as Plutarch, although in no doubt that Caesar’s death was a result of a conspiracy, nonetheless attributed cosmic significance to his demise, retrospectively identifying omens and portents foreshadowing and following the event. A comet filled the skies for seven days and the sun shone feebly for a year, he tells us, suggesting that the conspirators were merely players in a larger, pre-determined design.

Today’s conspiracy theories, without which it seems no contemporary assassination can be discussed, fulfil a similar function. They readdress the perceived power imbalance inherent in the idea of the little guy taking down the head of state. Said Jackie Kennedy of Lee Harvey Oswald’s role in JFK’s death: “He didn’t even have the satisfaction of being killed for civil rights … it had to be some silly little Communist.”

Now, 50 years on from the fatal shot in Dealey Plaza a widespread refusal to believe in the capabilities of “some silly little Communist” has led to a hydra-like body of conspiracy theories that has now taken on a life of its own, seeming only to grow more vigorous and complex the further the event recedes from the present.

Contradictions in the official version of events, issued prematurely and under duress, aroused suspicion from the outset, only briefly assuaged by the findings of the Warren Commission in 1964, which restored public confidence in the lone gunman theory to 87% of the population.

Post-Watergate, with faith in US authority at an all-time low, the conspiracy theories re-emerged and continue to gather momentum to this day, reverberating, seemingly infinitely, in the echo chamber that is the internet.

We do not yet know what conclusions will be drawn from the investigation into the suspected poisoning of Yassar Arafat.

Whatever the facts and final verdict of this highly charged investigation, they will reinforce what has by now become the default position of mistrust in official versions of events. Disraeli’s comment may once again be called into question.