On 30 March 2011, a truly unprecedented event took place at a provincial court in Loja, Equator, located some 270 miles from the capital of Quito. The Vilcabamba River, a plaintiff in a trial there, convinced the tribunal that its own rights were being undermined by a road development project. The project was then halted due because it would have jeopardised the river’s flow.

I was fortunate to be able to both attend this trial and examine what has been termed “legal animism” in two pioneering countries in the field, Ecuador and Bolivia.

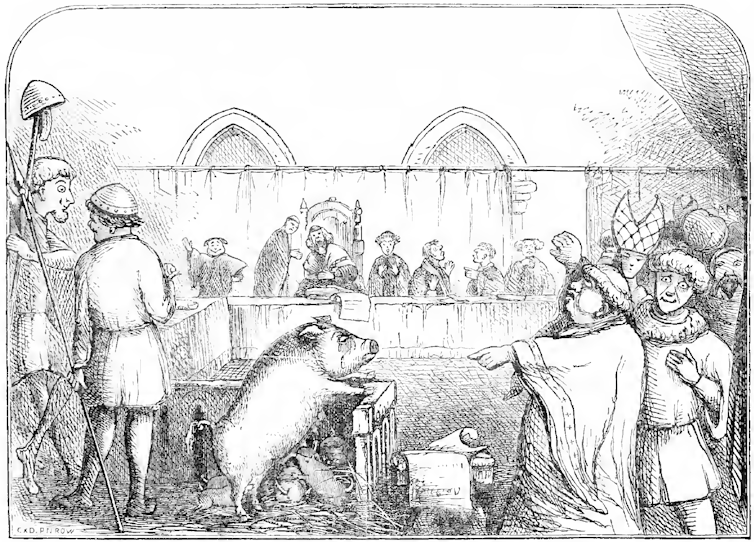

Today, nations from Uganda to New Zealand are following suit by opening up their criminal justice systems to this type of jurisprudence that enables a natural entity, be it an ecosystem or indeed nature itself, to become a legal person and thus have rights. These innovations are raising hopes among some environmental activists, but they also remind us of the law’s malleability. From animals being called to stand trial in the Middle Ages to the Indian lawyer who sued a god, we have sculpted our laws in creative ways throughout the eras. Indeed, no one finds it odd nowadays that a business is considered a legal person.

When two worldviews collide

By delving into the origin and development of the innovations in Ecuador and Bolivia, we can also observe how legal animism plays out in all its various guises, possibilities and limits. This is what I intend to do in this article.

South America may have blazed the trail, but the expression “legal animism” actually appeared for the first time in the writings of French legal researcher Marie-Angèle Hermitte. Right off the bat, this compound term connotes a meeting of two worlds and two philosophical traditions. In one corner, we have the animist worldview, which some Western schools of thought have portrayed as their antithesis; in the other, a system that forms the bedrock of European modernity.

In Ecuador and in Bolivia, we can find a common undercurrent of influences or frictions that pervades these two colliding worldviews. All at once, influences from North American environmental lawyers meld with the use of the divine Earth Mother figure present in Andean cosmogony.

Constituent Assembly: the moment when the natural world became redefined

Another commonality between these two nations is the rather specific context of the constituent assembly. In 2006 and 2007, respectively, Bolivia and Ecuador essentially wiped the slate clean by introducing assemblies tasked with drafting new constitutions. In doing so, they each witnessed a watershed moment of redefining their entire national identity.

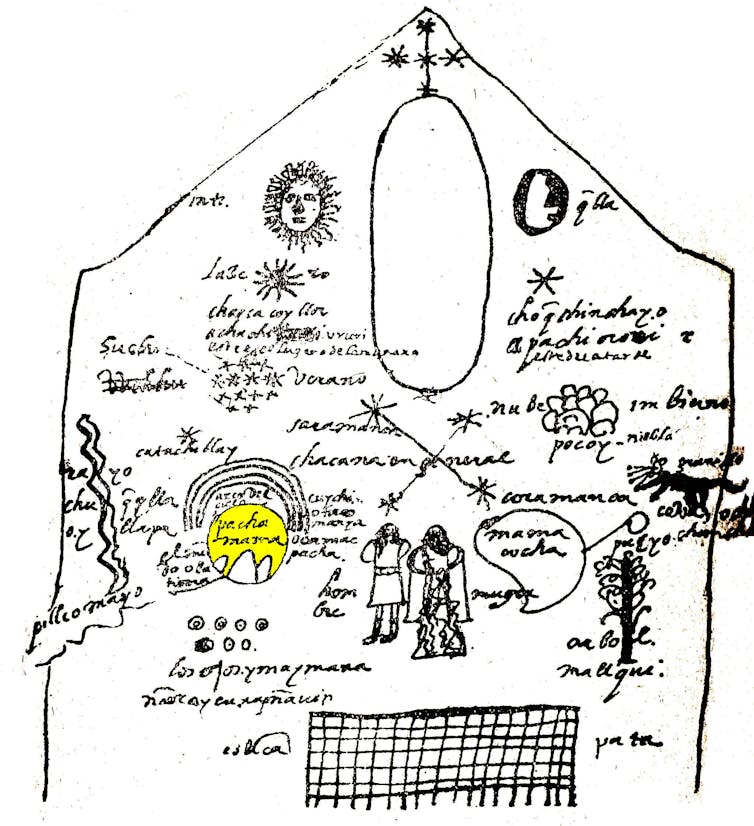

Supported or even long awaited by Native communities in both countries, these changes led to a rising prominence of the figure of Pachamama, the embodiment of Mother Earth in Andean myth. Also evoking a meeting of two worlds, this name is a portmanteau of pacha, the Quechua and Aymara word for “world”, and mama, the Spanish word for “mother”. Out of these circumstances soon came a wave of aspirations to endow nature with a legal status.

In Ecuador, legal animism was brought into the constituent assembly by intellectuals aligned with new theories of the law. They’re influenced by the concepts of US legal expert Christopher Stone, who proposed, as early as 1972, that trees should have rights. To ground these ideas within the constitutional context, the advocates relied on reinterpretations of the country’s Indigenous knowledge. In fact, 80% of Ecuadorians are mixed-race European and Native, but virtually the entire population identifies as Christian. It was out of these disparate influences that Article 71 of the Constitution was born. It stipulates:

“Nature, or Pachamama where life is reproduced and occurs, has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes. All persons, communities, peoples and nations can call upon public authorities to enforce the rights of nature.”

Article 72 evokes the right for an ecosystem to be restored, while Article 73 cites the requirement to enforce the precautionary principle for activities that might lead to the extinction of species, the destruction of ecosystems and the permanent alteration of natural cycles.

The figure of Pachamama

In Bolivia, constituents found themselves debating Pachamama’s specific attributes. On one side were residents from the highlands, who honour this deity each day; on the other were people from the lowlands and the south of the country, who had an altogether much more nebulous notion.

Pachamama’s scope of enforcement was also the subject of fierce discussion. If Mother Earth is omnipresent, must all living things be included in her definition? What are her limits? I had the chance to attend a debate that sought to ascertain whether, if Pachamama were considered a legal person, it would be possible – or indeed desirable – to sue a mosquito for biting a human.

These discussions culminated in a conceptualisation of Pachamama as an open-ended, collective entity; a Mother Earth across all planes of existence who should therefore be protected as such. This was to avoid the endless back-and-forth of determining what could or could not be included in her definition. Thus regarded as the mother of all things, her definition extends to every entity in the world. In the new constitution of 22 January 2010, no fewer than 10 articles mention Mother Earth based on these terms:

“Mother Earth is a dynamic living system comprising an indivisible community of all living systems and living organisms, interrelated, interdependent and complementary, which share a common destiny. Mother Earth is considered sacred, from the worldviews of nations and indigenous peoples.” (Article 3)

Articles 5 and 6 set out the legal framework of Mother Earth as a “collective public interest”, affirming that all Bolivians can exercise the rights of Mother Earth, provided that they also respect individual and collective rights.

Article 7 then goes on to list the seven rights of Mother Earth, which are the right to life, to the diversity of life, to water, to clean air, to equilibrium, to restoration and to pollution-free living.

This article is brought to you in partnership with “Your Planet”, an AFP audio podcast. A creation to explore initiatives in favour of ecological transition, all over the planet. Subscribe

The permutations and limits of nature’s newfound rights

With this new relationship to nature being enshrined in the two constitutions, what real-world consequences and applications have followed on from the legal tools that they have inspired? Again, Bolivia and Ecuador differ somewhat.

The Ecuadorian constituents’ desire to offer practical legal tools quickly gave way to legal actions, the first of which was the case of the Vilcabamba River. This trial was spurred by environmental activists who back in 2011 were already well versed in the law’s new potential, but we have since seen other proceedings led by a diverse cross-section of Ecuadorian society.

The tools proposed by the new constitution soon outstripped the limits expected of them by ecological struggles across the world. In this respect, it was presumed that it would be tricky to isolate responsibility for cases concerning the environment. For instance, how could a project, organisation or person be held accountable for environmental damages if those damages were suffered beyond the borders of the offending country? The Ecuadorian justice system has managed to extricate itself from these issues by invoking the precautionary principle and universal jurisdiction.

In November 2010, citizens from Ecuador, as well as India, Colombia and Nigeria, pressed charges against British Petroleum before the Constitutional Court of Ecuador. After the company caused a colossal oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the plaintiffs demanded that it release information on the ecological disaster and its impact, and that it repair the damages caused. These citizens were not direct victims of the oil spill and were therefore not suing on behalf of their own rights, but of those of the ocean. Although the complaint was heard, the judges ultimately decided to dodge the issue, citing another constitutional framework that imposed a notion and scope of territoriality on legal cases.

By comparison, the Bolivian constituent assembly has done little in the way of offering simple recourse to the law for defending the rights of nature. Nevertheless, the drafting of the new constitution centred on the figure of Pachamama has not been a futile exercise.

In particular, there has been some disillusionment regarding the gap between the ambitious ideals built upon the rights of Mother Earth and the reality of ongoing projects to exploit natural resources. This has put the government in a difficult position. It declares Mother Earth as sacred on the one hand, but on the other, it has also been entrusted with managing business as usual – or even developing it further – across all economic sectors.

This disparity has a fuelled a certain anger, with the figure of Pachamama being used as a cornerstone of several struggles. Among them is the movement to stop the construction of a road leading to the region of TIPNIS, a natural reserve of the Bolivian Amazon. Against the “developmentalist” arguments of the Bolivian government, farmers’ organisations, Natives and civic committees alike have cited the rights of Mother Earth as guaranteed in the nation’s constitution.

Backed by citizen support, particularly during two marches toward the capital, this movement saw an initial victory when a law was passed to establish the national park as an “intangible zone” and when plans to build the motorway were scrapped in October 2011. However, this was reversed in 2017. President Evo Morales, for his part, lost considerable support from Native populations throughout this case.

Backtracking and side-tracking in all directions

What can we learn? Such legal innovations may well have sparked a number of legal and political actions, but the law cannot do everything. It remains, above all, subject to the whims of political situations, as malleable for environmental struggles as it is for the demands of extractivism.

It can be common for backtracking to occur. In Australia in 2019, the Aṉangu Aboriginal population decided to ban tours of Uluru despite the substantial financial boon that these visits represented. This was because mass tourism to this sacred site was exacerbating erosion and groundwater pollution.

In recent years, Ecuador and Bolivia have stayed true to their reputation as breeding grounds of legal innovation. For instance, the Bolivian Mother Earth Authority, headed by Benecio Quispe, considered potentially expanding the law to include rights for objects.

Confronted with the global problem of waste management, the Mother Earth Authority opened up discussions with chiefs of Native communities and trade union leaders on the subject of legal rights for manufactured objects and goods. These included the right to a maximum lifespan, care, repair, non-abandonment and so forth. While this avenue ultimately led to nothing, it once more demonstrated the ability of legal tools to help redefine our relationship with ecosystems and the modern world.

This article is part of a project between The Conversation France and AFP Audio, supported financially by the European Journalism Centre, as part of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation “Solutions Journalism Accelerator” initiative. AFP and The Conversation France have maintained their editorial independence at every stage of the project.