The hung parliament is almost done. Surely we won’t see its return to the chambers. If Kevin Rudd wanted to reassemble the parliament before the election, he would need half a dozen cattle dogs to round up all the MPs on his side and enough crossbenches, especially those not standing again.

But then again, we are dealing with Rudd! So nothing can be taken for granted.

The 43rd parliament has been one of the most dramatic roller coaster rides of modern federal politics.

It has got a bad name from its many critics, seen as raucous, often on the brink of falling apart, and full of the worst sort of wheeling and dealing. It has, on this view, contributed to public cynicism about politics. It has not brought the “gentler, kinder” approach that some looked for; it was certainly a “new paradigm” but not always a good one.

Its defenders however, including the government and key crossbenchers, point to its legislative achievements, its survival, and the opportunity it has provided for the House of Representatives to act more like a true “parliament” where outcomes are more fluid, rather than the usual blunt-edge majority rule.

It’s time for an audit, and in this context, worth taking in also the experience of the previous hung parliament seven decades ago, before drawing some observations and lessons from the present one, including how our leaders have let us down.

Earle Page, after whom this lecture is named, was a member of that hung parliament of 1940-43, during his marathon parliamentary career, which stretched from 1919 to 1961.

Page, one of the founders of the Country Party (now the Nationals) and its leader from 1921 to 1939, was in the tradition of strong figures thrown up by a party that always has had only minority federal representation but often punched above its weight.

Page was tough and controversial. After Joe Lyons’ sudden death in April 1939 Page became Prime Minister for 19 days. He spent much of that time trying to entice former PM Stanley Melbourne Bruce to return to Australia to lead the government, in an attempt to head off Robert Menzies, whom he hated.

This effort was in vain, and on the day Page resigned his commission he launched an extraordinary parliamentary attack on Menzies, which divided the Country party and ultimately led to Page’s quitting the leadership.

Menzies became PM and took the government to the September 1940 election, which produced the hung parliament.

It took 17 days to resolve matters after the 2010 election, but five weeks in 1940.

Page became minister for commerce. But after Menzies had lost the support of his followers and had to resign in favour of Country Party leader Arthur Fadden, Page was sent as Australia’s special envoy to the British war cabinet.

It’s notable that those with Country Party or Nationals links have been at the crossbench centre of both the early 1940s and the present hung parliaments. It is not too much of a stretch to see this perhaps as reflecting the slightly different positioning historically of the rural party from the main conservative force.

One of the two independents who brought down the Fadden government in October 1941 was Alexander Wilson, who entered parliament in 1937 for Wimmera as representative of the Victorian United Country Party, beating the sitting member, from the Australian Country Party.

In the present parliament, more than half of the eight MPs who have sat on the crossbench for all or some of the three years have had links to the Nationals.

Tony Windsor, MP for New England, was once a party member (though not while he was a state or federal MP); he left after failing to win a state preselection. Rob Oakeshott started out as a National Party MP in the NSW parliament before becoming an independent there and later in Canberra.

Bob Katter represented the National Party in the Queensland parliament and federally before turning independent and eventually forming his own Katter Australian Party.

Tony Crook, from the WA Nationals sat on the crossbench in this parliament for a time before going to the Nationals party room. As well, Peter Slipper, who defected from the Coalition to become Speaker and then joined the crossbench when he had to quit that position, started his parliamentary career in the National party, later becoming a Liberal.

In those dramatic, exciting agonising 17 days in which the crossbenchers decided whether Julia Gillard or Tony Abbott should be prime minister, Windsor and Oakeshott went Labor’s way, allowing (with Tasmanian independent Andrew Wilkie) Gillard to form government, while Katter and Crook favoured the Coalition.

Rodney Cavalier, one-time NSW ALP minister who writes extensively about Labor, assessed the 1940s parliament in an article published in September 2010. Its essential message was reassuring - that a hung parliament had worked.

“Two governments fell during the course of this parliament”, he wrote - they were the Menzies one due to internal dissent and the Fadden government on the floor of the House. “The parliament passed 208 acts. Much of the work of government was pursued via regulations … The Senate was hostile to Labor … yet Labor suffered few defeats and none that mattered.”

Cavalier also pointed out that the hung parliament passed the Statute of Westminster, asserting Australia as a sovereign nation, and legislation for uniform taxation, giving the federal government a monopoly of income tax collection.

“Out of those arrangements, the Commonwealth has gained ever more power over the public policy of our nation,” he wrote.

Contemporary Australia “lives in the shadow of the 1940 parliament more than any other”.

In the 1940-43 parliament, the most damaging party infighting was on the conservative side, which led to the downfall of Menzies. The Fadden government, which survived only 40 days was shaky from the start. Fadden didn’t move into the Lodge; a colleague was on the money in advising him he’d “scarcely have enough time to wear a track from the back door to the shithouse before you’ll be out”.

In 2010-13, it was Labor that was at war internally, culminating in a Shakespearean act of revenge and restoration, when Julia Gillard was deposed by Kevin Rudd.

Gillard negotiated with crossbenchers, including the Greens, in order to keep Labor in power. Menzies, admittedly in the very different situation of wartime, tried to persuade John Curtin into an “all-party administration”, but Labor would not buy the idea.

The vote that brought down the conservative government and installed Labor in 1941 was not an ordinary no-confidence motion, but an amendment to reduce the budget by one pound.

This was not a blocking of the budget as in 1975 but a way of putting the future of the government on the line, recognised as such beforehand by both sides of politics and the two crossbenchers.

There were threats by the Abbott opposition during the current parliament of moving a no confidence motion against the government. But none materialised because the numbers were never there.

Both the 1940s parliament and this one lasted the full distance. In the present case, the government, and some of the crossbenchers, laud this as an achievement in itself. In this parliament, there has been a single change of government, involving the one side.

In the 2010-13 parliament the budget was never threatened, though some budget measures had to be negotiated through the House and/or the Senate. (Labor never controlled the Senate in this period.)

The hung parliament has brought heightened tension to federal politics over the past three years. It is important to note, however, that it has not raised questions about the fundamentals of the system in the way the governor-general’s sacking of a government did in 1975.

The opposition has questioned the government’s legitimacy because of the composition of the parliament. Manager of opposition business Christopher Pyne said at the weekend: “I do think it’s been a troublesome and unhappy parliament. There’s never been a sense on the opposition’s side that the government has been a legitimate one because they’ve been propped up by two independents who are in conservative seats. So I think for three years there’s been a sense that ‘we was robbed’”.

But a hung parliament works by virtue of informal or formal arrangements with crossbenchers, and the notion of owning seats is also a bit dodgy – Windsor, for example had been MP for New England since 2001. In the 1940s one of the crossbenchers who brought down the government was in a conservative seat and had recently been a member of the United Australia Party.

The Gillard government was no more “illegitimate” than, say, John Howard’s government after the 1998 election when he won a majority of seats but not a majority of votes. Sometimes the democratic system throws up quirks and we accept them as part of it.

It seems to me that the experience of this hung parliament has been that an untidy and unusual (at least federally) arrangement has worked in an ultimately orderly way.

Of course those, like Tony Windsor, familiar with state hung parliaments, regard this as a perfectly natural order of things.

People sometimes talk of the tyranny of the majority in a democratic system. When the House of Representatives is working normally, that indeed is what we get there.

In the Senate, it is usually (not always) another matter. The government of the day is often hostage to a minority.

The hung parliament extended the power of the minority to the House too.

Crossbenchers gave support in return for concessions, which varied from a promise to act on carbon pricing, to regional programs, parliamentary reform, and a pledge to run full term and much else. One thing going in favour of Julia Gillard was that the crossbenchers believed she was more likely than Tony Abbott to shy away from an early election.

At a theoretical level, critics say it is bad when a handful of people representing very few electors are able to determine whether major pieces of legislation pass or fail.

Further, those holding the balance of power extract concessions, general or for their electorates, as they negotiate on various items. This can produce undesirable distortions -why should the voters of New England do better just because its member is a crucial number compared with, say, those in Riverina or Mallee?

Supporters of the hung parliament argue that when a government has to negotiate with crossbenchers, that can lead to better legislation. And Windsor has talked up how regional Australians have been given a voice.

Parliament has a much more active role, rather than the House being a rubber stamp. The government is kept on its toes. Having the parliament “hung” is another check and balance in the system, so the argument goes.

The current parliament has actually achieved a lot. In formal terms, according to Parliamentary Library figures, it passed 561 acts from government bills, up from just over 400 in the previous parliament.

More than one fifth (22.1%) of these were opposed, much higher than the proportion in any recent federal parliament (looking at the last six parliaments, including this one, the next highest proportion of acts which had been opposed was just over 9%). The high proportion opposed tells us something of the fractiousness of the parliament, where the Abbott opposition has been particularly aggressive.

Of course the overall number of pieces of legislation passed doesn’t mean a great deal because much of it is pedestrian or non-controversial.

But the parliament did agree to a good deal of important legislation.

This included the carbon price package; the Gonski school funding arrangements (which has a provision for states not signed up to opt in); the disability insurance scheme (together with an increase in the Medicare levy to pay for it); a means test on the health insurance rebate; paid parental leave; a plan for the Murray Darling Basin; plain packaging for cigarettes; and the establishment of a Parliamentary Budget Office, which is available to cost policies on request.

Some of these bills got through with opposition support; others had to be negotiated with crossbenchers. While the government had deals with key crossbenchers to guarantee supply and confidence, legislation was usually a bill-by-bill proposition (except in the case of the carbon plan where there was an elaborate cross party process to draw up the blueprint).

The power of the crossbenchers has made this parliament a bonanza for private members. About a quarter of House of Representatives time has been used for private members business (in 2011-13). Some 357 private members bills and motions have been introduced and debated; 150 have been voted on and 113 supported, according to figures supplied by the Leader of the House’s office.

In comparison, in 2005 under the Howard government no private members motions were voted on.

Six private members bills have passed this Parliament. Wilkie got through legislation to protect journalists’ right to keep sources confidential. An Oakeshott bill allows the auditor-general more power to review people working for or subcontracting to the government. An Adam Bandt bill gave more rights to firefighters diagnosed with site cancers. Another Greens Bill, from Rachel Siewart, dealt with petrol sniffing. A bill by former Greens leader Bob Brown made harder federal intervention in ACT affairs. There was also an administrative bill from Senate president John Hogg.

One crucial private members bill, from Oakeshott, and supported by the government, that would have validated the Malaysia people swap after the High Court ruled it out passed the House but came to grief in the Senate.

The government’s practice during the hung parliament was not to proceed with legislation that was headed for defeat. For example, this year the government pulled a package of bills on media reform when it could not get a deal with the crossbenchers in the House.

What do the cross benchers think of the parliament? I spoke to or received responses from Oakeshott Windsor, Wilkie, Katter, Crook (who was a crossbencher for a period), and Bandt. (Slipper and Thomson, who were on the crossbench because of unusual circumstances and can be seen in a different category to the others, proved elusive.)

Unsurprisingly, the crossbenchers’ assessments are affected by whether or not they were major power wielders.

Those underpinning the government have done particularly well for their electorates.

Tony Windsor names the rollout of broadband and the development of the local hospital, among his local bonanza. Andrew Wilkie (who refused Abbott’s offer of $1 billion for a hospital) points to health and hospital money and reversing “decades of underinvestment” because his seat had been considered a safe one. Oakeshott says his electorate has done well.

Crook reports that he had only “little wins”, though significant, including funding for a respite centre. They were “to keep me in the room”, he said. He always knew that, being outside the key power loop, he’d have a hard row to hoe, but “I got sick and tired of the government knocking on my door and bringing nothing with them”.

While on the crossbench, he voted with the government on eight bills (including four in a health package) and his vote was critical for passing the special levy to finance reconstruction after the Queensland floods. After joining the Nationals party room he crossed the floor to vote with the government on a bill to advance deregulation of wheat marketing.

On the hung parliament’s major achievements, the disability insurance scheme is frequently mentioned, even though there was bipartisan agreement on that without the crossbench having a particular role.

Indeed Oakeshott says that the great lesson for him out of this parliament has been that “bipartisanship is the best and politically the only way to achieve long-standing reform”.

He admits that he’s had disproportionate power. “Because others stayed true to their party first, they’ve handed me more influence than any one MP should have”, he says, adding, “If they are going to hand it to me, I’ll take it and use it – and I have”.

It is often argued that the net negative of the hung parliament has been that it has frayed the national political psyche.

This shouldn’t be exaggerated. And it is not just the parliament’s fault that people are feeling particularly out of sorts with their politicians. The quality and quantity of media has a lot to answer for as well.

But the fact that the hung parliament meant an election was always a heart beat or two away, and that the situation was complicated by the scandal surrounding Labor MP Craig Thomson, adding to the uncertainty, meant that the political battle was on high-octane fuel all the time.

Add to this the aggressive style of the Abbott opposition and the more feral nature of politics in the social media age, with a lot of highly personal attacks in the blogosphere on Julia Gillard, and it is no wonder that by the end many voters are crying “enough”.

Windsor, speaking in his valedictory, referred to the “negative vibes that have been developed out in the community” about the hung parliament. He sees it as a failure of people to understand what it is. “In some ways they do not fully comprehend what a hung parliament is, and still look at it through the prism of the two party system. It is not that”.

Views vary on the crossbench about on whether the hung parliament contributed to the community’s disillusionment.

Katter says: “No - the disillusionment was there well and truly before the hung parliament. A hung parliament in other words is a multiparty democracy which is experienced everywhere else in the world. The two party system is primitive”.

Bandt puts the negatives down to the politics rather than the hung parliament itself. “Tony Abbott has successfully prosecuted an argument about instability and gridlock attributed to the minority government despite support for the government being very stable … The main contributor to this has been Labor’s leadership division rather than the hung parliament”.

Wilkie sums it up neatly. Regrettably this parliament has contributed to disillusionment, he says “though the very real public disillusionment is I think more to do with the people who populate the hung parliament. The parliament itself has proved to be remarkably stable, reformist and productive.”

My own view is that if we look at this parliament and that of the 1940s the key problem has been less the hung parliament as such than the issue of leadership.

Curtin as PM had more authority than either Menzies or Fadden. A restored Rudd has more authority than Gillard.

In the early stages of the ‘40s parliament the internal troubles on the conservative side contributed to an impression and reality of disorder.

In the current parliament Gillard’s lack of authority shaped perceptions negatively. If Gillard had recovered after the election and her poll standing had risen, the narrative of the parliament might have been seen in a different light.

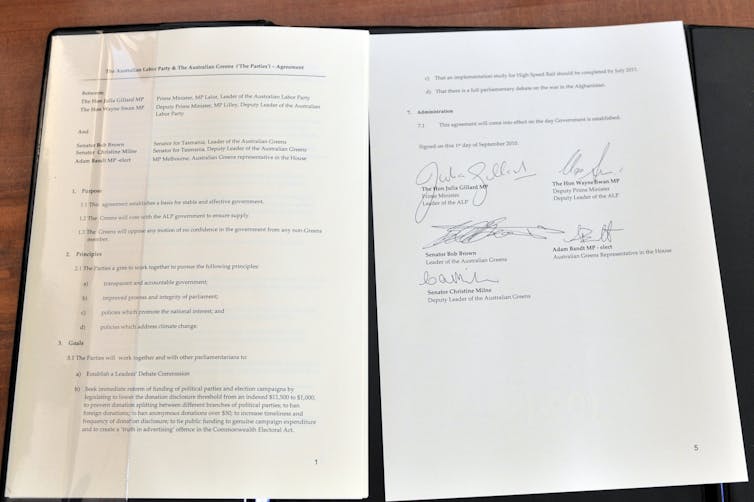

Gillard made a strategic mistake in entering a formal alliance with the Greens. It is hard to see where else the Greens had to go so arguably she did not need to go so far. The price of her agreement was breaking her word on the carbon tax, which turned into a disaster for her.

In his just-published book Hearts & Minds: A Blueprint for Modern Labor Chris Bowen, now the Treasurer, contrasts Curtin refusal of Menzies’ offer of a national government with the deal with the Greens. “Curtin was right and his dictum should be adopted again now”, Bowen writes, saying that in future Labor should govern alone or not at all.

Bowen writes: “It’s one thing to accept the support of some independents to form a government (as Curtin did in 1941). It is quite another to make concessions and compromises with a political party with a quite different philosophy in order to form a government. I think that the Australian people question what a political party really stands for when such agreements are made”.

By the end of the hung parliament the agreements underpinning Labor in power had broken or frayed although the edifice propping it up was still intact.

Wilkie scrapped his agreement when Gillard backed away from her commitment to deliver gambling reform, although there was no serious prospect of his joining any attempt to bring the government down.

The Greens also backed away from their alliance, and have become fierce critics of the government on aspects of carbon policy.

The Greens had got all they could from the government and needed to differentiate themselves in the run up to the election. And the government now is heading off in its own direction, bringing forward the ETS, to the fury of the Greens.

In speculation ahead of Kevin Rudd’s return there was talk of whether the key crossbenchers, notably Windsor and Oakeshott, would try to take him down. Their agreements were with Gillard, not with Labor as such.

In the end, this became a non-issue.

Rudd’s restoration came on the penultimate day of the House of Representatives sitting. It was the day Windsor and Oakeshott announced they would not recontest their seats.

Suddenly the key crossbenchers and their deals with Gillard (which included consultations on election timing) seemed totally irrelevant.

Crossbenchers of the future will no longer be courted – they can expect only small pickings.

Before Windsor withdraw as candidate for New England, the Nationals candidate, senator Barnaby Joyce was campaigning on the line that the seat needed someone with a place at the table – that with a majority government an independent would have no sway.

It remains to be seen how many of the parliamentary reforms that were negotiated at the start will survive when majority government returns. Some will; others will be pared back for the convenience of the government of the day.

One big question is whether the temperature will return to more normal levels when (assuming it’s not if) we return after the election to majority government.

Somehow I doubt it. The hung parliament will go – surely lightning could not strike twice in our time - but the hyper media cycle is unlikely to. We probably have established a new normal

And what of those crossbenchers, who’ve had the limelight? Windsor, Oakeshott and Crook are bowing out. Thomson and Slipper will be defeated if they recontest. Bandt will struggle in his seat of Melbourne; Wilkie is currently rated a reasonable change in Denison. The interest will be in Katter – not whether he holds his seat, which is expected, but whether his party might have a share of the balance of power in the Senate.

Let me end by drawing some observations and lessons from watching this parliament.

It led to Julia Gillard doing things that compromised her integrity and worked to her disadvantage. The entanglement with the Greens resulted in the broken promise on carbon. Then she stood by Craig Thomson when, if she had had a majority, he would have been pushed out of caucus much earlier. Thirdly, if the parliament had not been hung, the Labor-Peter Slipper deal for him to become Speaker would not have happened. So, as well as making government more difficult and complex for Gillard, the hung parliament brought out a whatever-it-takes streak in her character.

The hung parliament played to Abbott’s aggressive and bovver boy side. The close numbers and Gillard’s unpopularity meant he could just create a storm for much of the term, rather than having to act like an alternative PM. This served him all right when he was facing the former PM, but has left him poorly equipped now that he is confronted with Kevin Rudd; he is looking flat-footed and out- manoeuvred.

The uncertainty of the hung parliament played into the hands of Rudd’s bid to make a return to the leadership. Everything was always on a knife edge, making destabilisation easier and more effective.

This parliament gave the Greens their greatest opportunity. They were able to force Gillard into earlier action on carbon that she would have taken under the consensus path she promised at the election, and they influenced the form of the scheme. But by the end of the parliament, the Greens had taken a knock. In this week’s Nielsen poll their vote was 9%. Their problem is partly having lost Bob Brown, but also a reaction against the perception that the tail wagged the dog too vigously.

The hung parliament has been a high point in the power of independents but this too has produced a reaction. Politics is often about excess. When John Howard won the Senate, he went for broke with WorkChoices, to his ultimate cost. It is good for minorities and individuals to have voices but too much voice distorts the system.

The hung parliament has been more efficient and effective than many predicted, but it has left politics with an even worse name than it had before in voterland, where the description “toxic” is often applied. It may not have been as bad as people thought, but their perception can be as important as the reality.

This parliament has thrown up an important question about political leadership – that is how a good leader balances partisanship and bipartisanship. No leader wants to give their opponent an advantage. But making everything partisan fans public cynicism and damages the body politic. The line is always going to be difficult to draw, but it hasn’t been well drawn in this parliament.

What is the ideal Parliament? In my view, one where there’s a majority government with a margin that is workable but modest enough to keep arrogance in check. And with a Senate that respects clear government mandates on big issues but is an active watch dog.

Having said that, let me make one confession. We journalists will miss the hung parliament. It’s had more than a touch of excitement about it, from beginning to end.

This is the text of Michelle Grattan’s Earle Page lecture, delivered at the University of New England.