Art and politics have long been bed-mates – perhaps most notoriously from a perspective of protest, but also through visionary modes as well. Art is a vehicle through which “what is” can be replaced by “what could be”, whether through an angry violent voice or an optimistically utopian one.

But more recently art has developed a more nebulous relationship to politics. This May, there are two artists running in the general election. One, known as Bob & Roberta Smith (Patrick Brill) has a clear message: he wants art and art education to be recognised and promoted as a valuable part of society. Artists in the constituency of Surrey Heath will no doubt vote for him for obvious reasons.

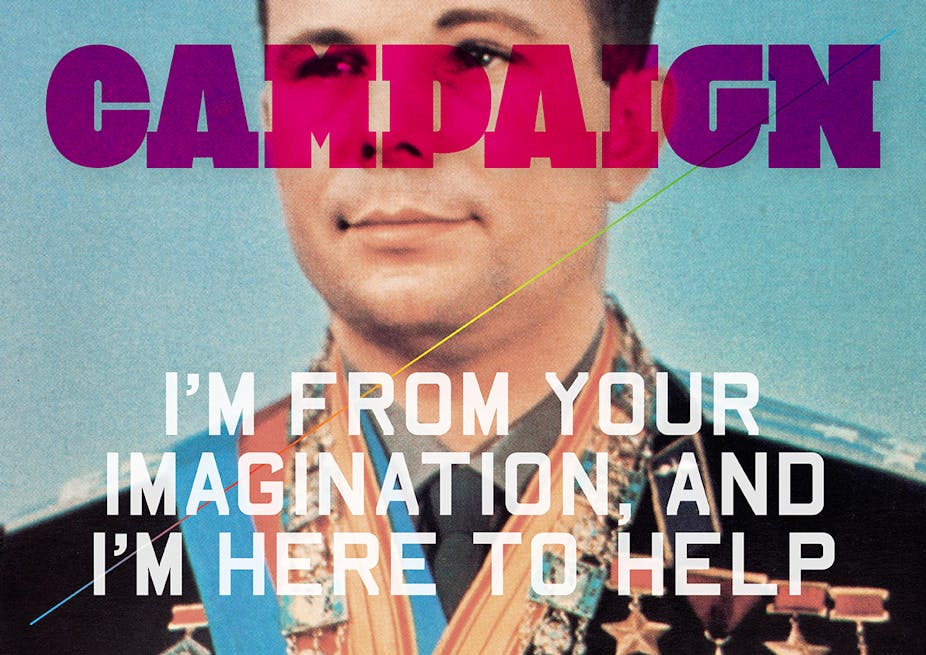

But the artist/architect Gordon Shrigley is also running in Hackney South and Shoreditch. And Shrigley, in his own words, has nothing to offer but offer itself.

So who would vote for a candidate that admits he has absolutely nothing to offer? What is enticing about a candidate with nothing to say? Is this about some gloomy comment being made about the state of our society? I caught up with Shrigley at Hackney’s The Laundry (his choice) and asked him why now is the moment for an artist to be running a content-less campaign.

Lois Rowe: Why now? Is there something about this moment that feels timely for an artist to be running?

Gordon Shrigley: Well it was a reaction to the amazing energy and creativity of all the different protest movements that came out of the banking crisis. Apart from the obvious ones like Occupy there were lots of sub-groups. There was a group coming out of Greenwich University that used to give lectures on economy in bank foyers on an ad hoc basis. There was so much going on. It was noticed by commentators at the time that a lot of alternative narratives being used were coming from the 19th century. So, you know, the sales of Das Kapital went through the roof. I speak as a former member of the Communist Party.

Rowe: And how did your reaction to those movements and their concerns lead to your current campaign?

Shrigley: Obviously I don’t have any policies because I’m not a politician. And also there is a history of the independent maniac standing up and thinking they have all the answers for the world and they either go and live in a shed and write some long manifesto and start blowing people up or they stand as some crack-pot in the election. And obviously there is a history of that which you could fall into, but that would be to limit the possibilities in a way. The idea with the campaign is to create a clearing where the possibility for new narratives is open. It creates a question really. Because the question is not really there. It is and it isn’t in a sense.

Rowe: Are you sincere about this desire to create or provoke new narratives or is the campaign ironic? The reason I ask is that for me there is a confusion for me around the agenda of the campaign. I know that Jonathon Jones took a swipe at it and said if you were to win it would mean one less Labour MP and one more expression of nihilism … And I can see where he’s getting that from because one of your campaign slogans is “I have seen the future and it doesn’t exist”.

Shrigley: I mean that in the sense that the future has not yet been written …

Rowe: Well that statement for me says “there is no future” … which is nihilistic.

Shrigley: That isn’t a problem. And I know people will read and misread things and that is part of the discourse.

Rowe: So you don’t really have a strategy or ambition towards actually having a seat per se. I mean, what would you do if you won? Would you be interested in getting more funding for the arts? That would make me vote for you because I could say here is someone who is going to stand our corner.

Shrigley: Patrick Brill is standing on a classic arts left-wing ticket. And I think that’s totally fine but I think it’s very archaic in a way. And I think it would be very shortsighted of me just to promote my own social group. In a way that would be a very simple way of deconstructing the whole thing. So I’m not standing for artists.

Rowe: So you’re standing for “the people”?

Shrigley: No, I’m standing for the potentiality of the space of the imagination that we all have … So let’s just say that I’m shot to fame on a whirlwind of whatever and I find myself in parliament. What would I do? I think I’d do exactly what I’ve done all the time. I think I’d just practice art. Because art – well good art – is the production of new possibilities, new ways of thinking. I think that would be what I would do.

I left the interview somewhat bewildered as to who will understand enough of the Shrigley manifesto to care about his political intentions. How will phrases like the “potentiality of the space of the imagination” appeal to potential voters? Surely it’s better to cast your vote on a candidate that promises something rather than the certainty of nothing at all?

For Shrigley it is the form of the campaign – the form which is his mere status as a contender occupying a place in which conversation can happen – that is of greater value than filling that space with agendas or policies. Like protests such as Occupy it is the facilitation of dialogue and the promotion of new possibilities that activate the work.

But who will vote for him? What would he do about the real problems in politics like immigration and education funding? I asked Shrigley directly what he would say to a mother asking him about childcare reforms and he said he would predict a reply along the lines of:

I don’t want to answer that question but have you thought about this … Your question is motivated by a structural narrative that we all fall into.

I don’t think dialogue gets much more political than that. The audience for Shrigley’s campaign therefore is questionable. I expect him to alienate the most patient of potential voters. He is interested in facilitating a space for new narratives. Good art – and I agree with him – does this. It provokes viewers to question assumptions and produces new possibilities. It provokes its audience to do so. But whether an artist can do so with an empty campaign? I’m not convinced.