As the summer comes to an end and a new academic year approaches, another wave of soon to be university students are eagerly awaiting the next stage in their educational journey.

For many of these students, it will have been a summer of firsts: first time on holiday with their friends, first time preparing to move away from home, and the first time voting in a general election.

This was an election that saw youth turnout reach a 25-year high and many young people were motivated to vote for the Labour Party – at least partly because of a promise to abolish university tuition fees and to reintroduce maintenance grants.

This spike in youth political mobilisation came as a surprise to some, but less so to those who work with young people. When fees were capped at £9,000, the most disadvantaged students were looking at graduating with as much as £57,000 in debt. While it is tempting to think that debt is a problem for the future, it seems to have an immediate and egregious impact on student mental health.

In 2015, an NUS survey found that 78% of students had experienced mental health issues in the preceding year. The outgoing welfare officer at my institution’s Students’ Union, Anna Mullaney, explained that students of her generation:

Live and breathe in the context of a complex and constant mental health crisis.

While fees are not the only factor to consider – the graduate job market, the cost of housing, and the evolving use of social media also loom large – students’ current and future financial situations are central to their concerns. And with some institutions set to raise their 2017 to 2018 fees to £9,250 and interest rates on student loans rising to 6.1%, we can only expect this trend to deepen.

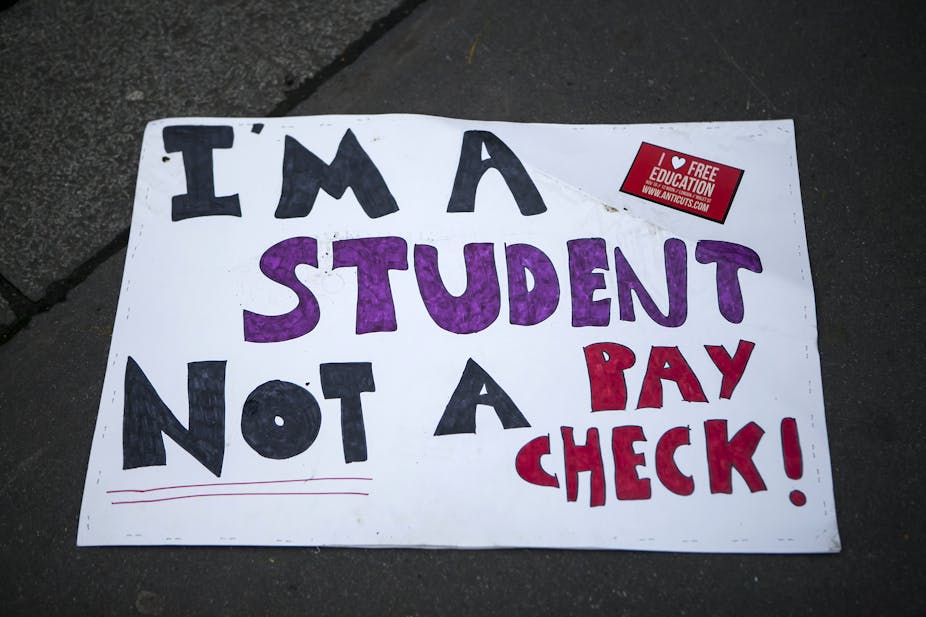

Yet, while the financial specifics negatively impact on student well-being, they form part of a multifaceted trend in higher education, namely, “marketisation”.

In 2016, then NUS vice-president for welfare, Shelly Asquith, warned:

[The] marketisation of education is having a huge impact on students’ mental health. The value of education has moved away from societal value to “value for money” and the emphasis on students competing against each other is causing isolation, stress and anxiety.

Whose benefit?

When fees were first introduced, it was pointed out that graduates earned comparatively more over a lifetime than non-graduates. The implication was that they should therefore carry some of the associated cost.

This focus on earnings is part of a wider trend where the “value” of undergraduate education is reduced to private gains made by graduates. This is typically in the form of higher earnings and higher rates of employment compared with non-graduates.

But what is missing in such talk is the sizeable public benefits derived from living in a society populated by more, rather than less people with university degrees. These public benefits include increased tax revenue, higher exports, higher productivity, lower public health costs and reduced crime rates.

Having more people involved in higher education also improves civic participation – through voting and volunteering – and it helps to generate higher levels of public trust and tolerance, as well as making cities more dynamic.

Public values

But it is not just graduates that yield public benefits, universities as institutions do so as well. Not only do they produce and communicate world-class research, universities connect localities to the wider economy and have the potential to help attract foreign investment and support specialised skills development.

From a cultural standpoint, universities act as international hubs, attracting students and staff from all over the globe. Moreover, they help to foster diplomatic goodwill towards the UK (which has become scarcer since Brexit) thanks to connections with international students and international partner organisations.

And, despite growing pressures to fully embrace market competition, many people working in public British universities remain committed to the idea that higher education can and should serve the needs of society. They aim to educate for a life of engaged citizenship and are attached to the notion that knowledge and understanding provide the only stable grounds for technological, cultural and political progress.

Common endeavour

But in spite of the deep changes to the sector over the past two decades, it is not too late to recover a sense of common endeavour. At its most general, this consists of fostering economic growth through innovation, evening out life chances and working towards solving major collective problems – such as, poverty, intolerance, violence, illiteracy, hunger, environmental degradation and disease.

But can universities be expected to be more publicly orientated when most of their financial support comes from tuition fees? I think not.

As a result, we might consider the urgent need to revise the current higher education funding arrangement to both reduce the strain on students’ mental health and refocus the connection between universities and their public goals. The health of Britain’s youth as well as the country’s future place in the world may well depend on it.