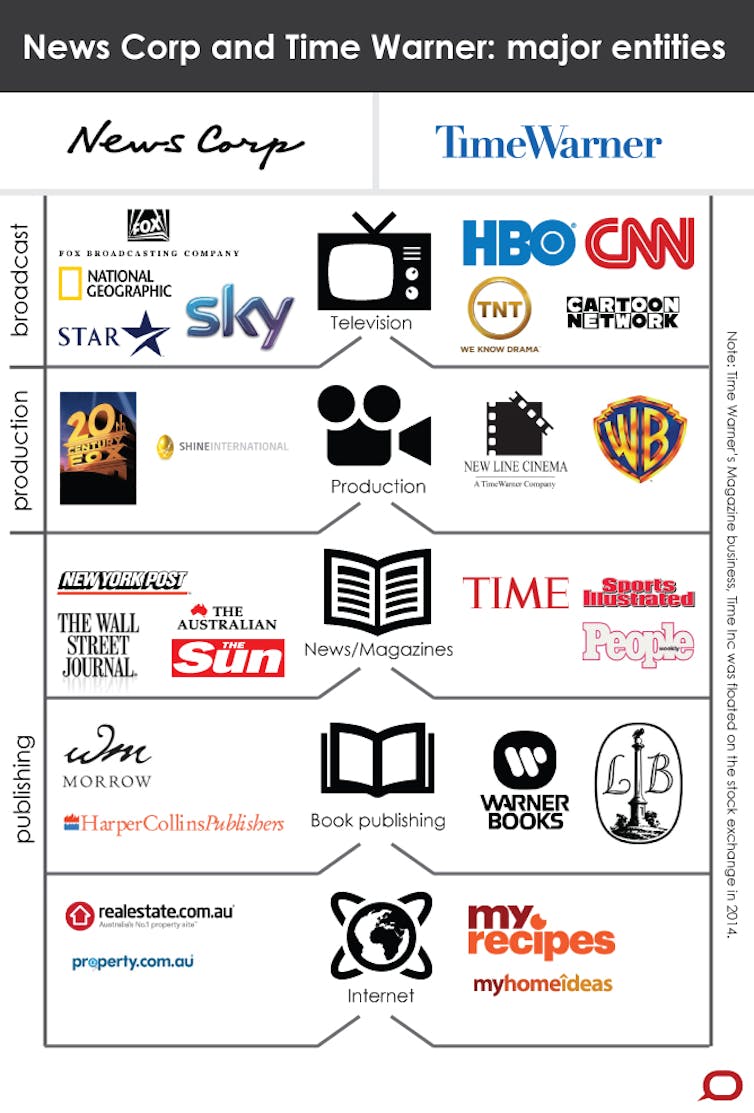

At age 83 Australian-born tycoon Rupert Murdoch is as restless as ever. He is anxious to add the behemoth Time Warner, owner of everything from HBO to Cartoon Network to Superman, to his already bulging portfolio. Over an infamous career, Murdoch has not only bought up TV stations and newspapers like The Times of London and the Wall Street Journal, but a panoply of properties such as publisher HarperCollins and the Myspace social network.

In the United States, Murdoch has been best known as a kind of nefarious puppeteer-cum-plutocrat, who uses his control of Fox News and the Wall Street Journal editorial page as a megaphone to advance a right-wing political agenda. However, Murdoch’s pursuit of Time Warner raises much broader questions about the fate of free and open media in an age of rapidly multiplying formats and platforms, but increasing consolidation of media ownership.

Indeed, the media scene in the United States and around the world today is Janus-faced. On one hand, technologies such as blogging, tweeting, and online video appear to offer the promise of democratisation, giving the street protester in Cairo or Kiev and the Wikileaks whistleblower access to a world audience. On the other hand, control of the most important and influential media outlets continues to concentrate in fewer and fewer hands.

We’ve actually been on this road for some time, as Murdoch’s storied career of acquisitions suggests. Way back in 1983, media scholar Ben Bagdikian warned control of American media was in danger of falling under suffocating, centralised control:

“If mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers continue at the present rate, one massive firm will be in virtual control of all major media by the 1990s.”

Bagdikian was writing in a time not unlike our own, when merger mania on Wall Street allowed a smaller and smaller coterie of big corporations to buy up an ever-bigger chunk of media real estate in the United States.

In the 1980s it was electronics firm Sony buying up CBS Records and Columbia Pictures; today it is Comcast buying rival Time Warner Cable and now Murdoch seeking TWC’s former corporate parent.

Of course, Bagdikian conceded that total control of media under one owner was unlikely, given the vicissitudes of politics and the American economy. So do we have anything to fear from such consolidation of ownership in our biggest and most influential media?

A history of constant change

The history of media in the United States has, in fact, seesawed back and forth between diversity and consolidation, from the democratic era of the nineteenth century, when nearly every town had several lively, mostly partisan newspapers, to the twentieth century, when most cities had one big paper.

As one format became ossified and staid, another new technology opened up new possibilities. For instance, in the 1950s and 1960s television viewers had only three big broadcast networks to choose from, but the rise of cable in the 1970s brought new options, such as CNN and HBO.

This history of dynamic tension in the media should provide no cause for complacency, though. Bagdikian’s dark predictions have, by and large, come true. Though not all American media have been consolidated under one, Big-Brother-like megacorporation, a mere four record labels control most of the world market in music, and eight companies dominate American broadcast and cable television. Similar concentration prevails in book publishing as well.

One could argue that focusing on such consolidation in a handful of older industries misses the point: a few movie studios or book publishers may dominate their respective fields, but that ignores the fact that new competitors using new platforms still create meaningful diversity. Consider new media upstarts like Talking Points Memo, which offers an alternative to traditional journalism and news reporting, or the challenge of new television content from Netflix or Amazon.

So many blogs, so little power

However, the diversity of options in new media may turn out to be a fig leaf, a distraction from the bigger and more important story of concentrating power in the media. There may be a billion blogs, but if you need to go through Comcast (your cable provider) to read them, the mega corporation has a great deal more power than the lowly, Cheeto-munching blogger — especially if the United States abandons its policy of “net neutrality,” a step that would allow the wealthier and more powerful privileged access to their content with faster internet speeds.

Indeed, if a handful of companies like Comcast and News Corp can gain control over both content (movie studios, record labels) and the infrastructure (cable), then we could face an alarming situation in which an illusion of diversity — anyone can tweet their opinion or record and upload a track to BandCamp — obscures the fact that a radically small number of corporate decision makers wield all the real power.

The interests of consumers are also at stake. As the United States embarked on its program of deregulating airlines, banks, and the media since the late 1970s, it simultaneously took an increasingly lenient view of antitrust issues. While deregulation initially created new options in the 1980s — new airlines, new telephone services and providers — it also led to considerable consolidation in these industries.

Unsurprisingly, the merger of airlines such as Delta and Northwest (in 2008) and Southwest and Airtran (in 2011) has resulted in higher prices for consumers. Not facing the pressure of competition, airlines feel free to raise fares — not unlike the situation with cable companies, which often enjoy local monopolies in the United States.

Bill Clinton once famously said that trying to control the internet is “like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall” — it can’t be done. His aphorism was from a more innocent age, when the democratising power of the internet was fresh and, mostly, untested. Governments such as China’s have made it clear that the restless and woolly beast of the internet can, in fact, be brought to heel.

Indeed, Murdoch’s move with Time Warner is just the latest gambit of the corporate world — along with rivals such as Google, Comcast, and Amazon — to bring new media under control and assure the safety of monopolistic profits into the foreseeable future. Consumers, citizens, and regulators ought to beware.