Leer en español.

Venezuela, the South American country convulsed by economic and humanitarian catastrophe, has defaulted on some of its debt after missing an interest payment due in October.

Even as investors meet in Caracas to discuss restructuring US$60 billion in foreign debt, the country is in urgent need of international financial assistance.

Yet few nations are rushing in to aid the ailing country. Under the authoritarian regime of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela is isolated in Latin America, and the United States, Canada and the European Union have all imposed sanctions against Venezuelan officials. Maduro has at times suggested he would not even accept humanitarian aid.

Still, no indebted nation is totally alone in this world. As a financial analyst, I know there are always international players who see opportunity in the problems of others. And for Venezuela, my home country, all hope of a bailout rests with China, Russia and the International Monetary Fund.

Will they do anything to help?

Venezuela’s debt: By the numbers

Before exploring a possible Venezuela rescue, it is useful to understand how the country’s debt became such a burden.

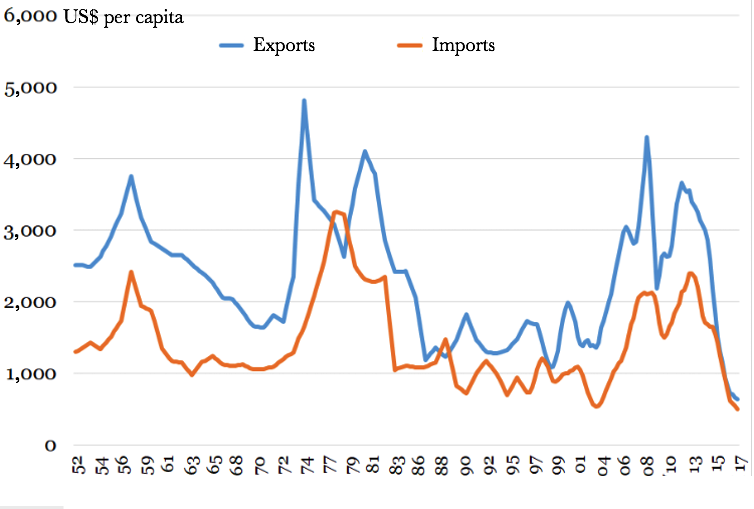

In 1998, the year before the late Hugo Chávez came into power, Venezuela was rich. It produced roughly 60 barrels of oil per inhabitant per year. By late 2017, my projections – based on data compiled from Venezuela’s National Statistics Institute and BP’s World Energy Report 2017 – show that production will have dropped to 20 barrels per capita. That’s a 66 percent drop in 20 years.

Even as output steadily shrank, Chávez benefitted from relatively high oil prices, which allowed him to boost revenue from petroleum exports. And as oil sales rose, so did government expenditures, as well as imports of food and other goods.

Eventually, excess spending took a toll on Venezuela’s international reserves. Rather than cut expenditures and imports, the Chávez regime piled up foreign debt.

Then, in late 2014, international oil prices began to plunge. Today, estimates indicate that Venezuela’s public sector debt tops $184.5 billion, including $60 billion in foreign debt, though the Venezuelan Central Bank claims it’s much lower.

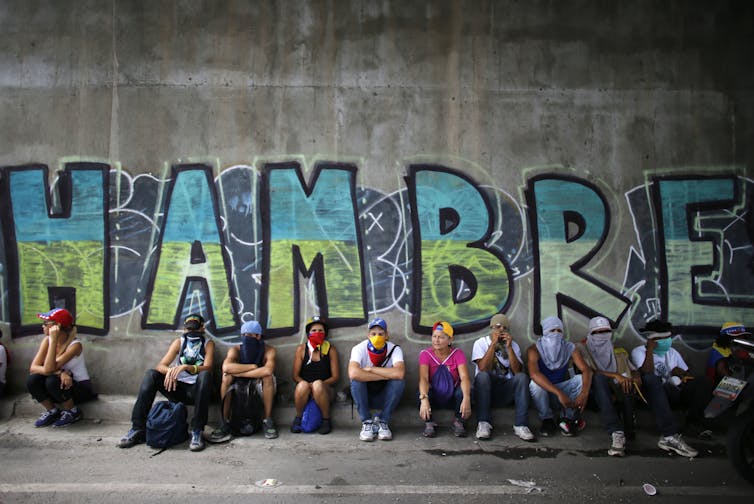

To service this debt, the government must pay $16 billion to $20 billion a year through at least 2022. Shouldering that huge expense has meant slashing imports, causing food and medicine shortages. As a result, almost 54 percent of Venezuelan children are malnourished.

To ensure its citizens’ basic well-being, Venezuela must be able to import, on average, $1,000 a year per inhabitant – or roughly $33 billion a year. My data show it’s currently bringing in about half that.

No Chinese largess

As an oil producer, Venezuela’s desperation rouses geopolitical interests.

Venezuela owes $28.1 billion to China and $9.1 billion to Russia, its main creditors. In recent years, both countries have been eager to prop up the Maduro regime, with little concern for its authoritarian tendencies.

China, at least publicly, has remained decidedly mum on Venezuela’s political crisis. According to a spokesperson from the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs in October, Beijing “believe[s] that the government of this country is able to appropriately handle its domestic affairs within the law, maintaining stability and prosperity.”

So far, though, Chinese financial institutions have not further opened their coffers. They have, however, granted Venezuela a grace period of at least 18 months to pay off the debt it owes them. This modest concession gives the government a bit of breathing room.

China has also allowed Venezuela to use shipments of crude to pay off some of its debt, revealing China’s main interest in Venezuela: its oil.

But, in my view, Venezuela shouldn’t count on Beijing for significant additional financial help. For China to issue new loans, insiders have told me, Maduro’s government would have to show clear signs of fiscal discipline. Nothing indicates it is capable of that.

I believe a more likely next step is that Venezuela will bring in much-needed cash by selling off existing stakes in oil companies and resource-extraction ventures it co-owns with China.

Putin to the rescue?

Russia has been somewhat more generous with Venezuela, and its geopolitical interests here are clear.

The Kremlin benefits from having a trustworthy ally on this side of the world – especially one that is avowedly anti-U.S. and ranked as the 11th-largest oil producer worldwide.

Plus, Russia already has many oil interests in the country, including joint exploration projects with Petróleos de Venezuela, the state-owned oil company.

Indeed, Russia and its state-funded oil venture, Rosneft, have already helped the country avoid default at least twice, providing Caracas with $10 billion in financial assistance. In an Oct. 29 New York Times article, oil expert Francisco Monaldi said Russia is “the only country that can toss Venezuela a lifeline.”

In my opinion, even its public declarations defending Venezuela’s politics are more incisive than China’s. Russia’s Foreign Ministry has called international sanctions against Venezuela “unacceptable.”

Still, thus far, Russia has agreed only to restructure its bilateral debt with Venezuela. While the terms weren’t disclosed, I don’t believe anything like a real bailout is on offer.

Last resource

This could lead Venezuela to its last resort: the International Monetary Fund. In my opinion, this global lender would be the most appropriate source of a bailout.

Neither China nor Russia is willing or able to offer the huge sum Venezuela needs to stay afloat, at least $30 billion. Nor is any country likely to match the super-low 2 percent interest rate that the IMF offers to emerging economies in crisis.

Bondholders typically look askance at this type of financial assistance. Countries receiving support from the IMF and other multilateral lenders are generally “advised to renegotiate foreign debt,” which can leave investors with empty pockets.

And today, Venezuela has no official relationship with the organization. The Chávez administration loved to disparage the IMF, saying it should “close down” or “vanish.”

Even so, there are signs that the IMF is sketching out a possible rescue plan for the country. Bank officials have expressed concern with both Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis and the possible spinoff effects of its economic collapse on other Latin American economies.

Since the multilateral organization is unlikely to bail out the current regime – which has previously rebuked its possible intervention – the IMF probably hopes to work with some future transition government that’s more democratic and open to international aid. If so, help may be a long time coming.