Over the next couple of decades, the UK is set to spend billions dismantling and removing the infrastructure used to extract North Sea petroleum. Most people think oil and gas companies will pay for it, but actually the taxpayer will fund a large proportion.

This state support will work through a system of tax breaks that will cover either 50% or 75% of decommissioning costs depending on the field. With the total cost of dismantling the UK North Sea estimated at about £40 billion, the taxpayer will hand over a huge sum of money – about £1,000 per head. And should decommissioning costs rise, as many suspect they will, the risk to the taxpayer is obvious.

Decommissioning has started already, costing £800m in 2014 for instance. But before the UK spends the majority of the fortune required, I believe the government should stop this process in its tracks. Instead, it should invest the money into something more beneficial to the future – renewable energy.

How decommissioning works

The process for decommissioning a field after petroleum extraction has become uneconomic is regulated by the UK government. First, the licence holder would typically seal all wells to prevent the oil reservoir from leaking into the surrounding environment. This is a complex process that requires the setting of cement plugs.

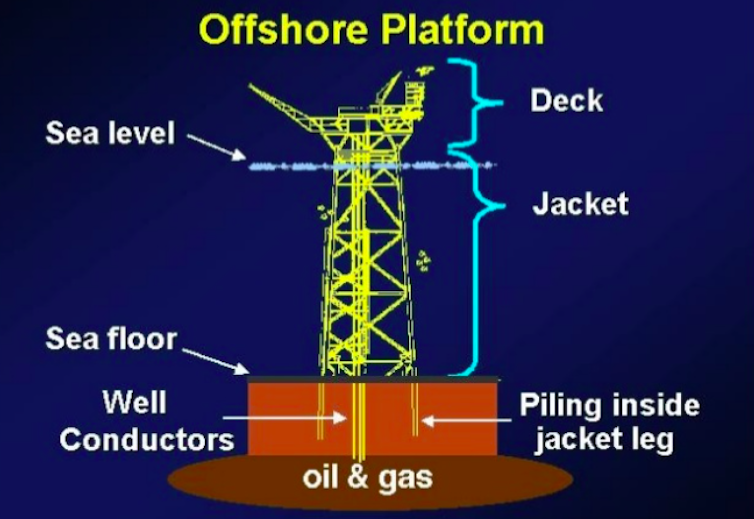

At the same time, the licence holder has to prepare the offshore facility for removal in two stages. It needs to first remove the topside, which consists of the equipment for oil and gas processing and drilling, then clean and section the equipment so that it can be lifted on to huge crane barges.

Then the licence holder needs to deal with the supporting structure, which is known as the jacket. This often consists of a huge steel frame attached to the seabed with steel piles. It has to be cut and then lifted onto a barge, as per the picture above, so that the entire operation can be taken onshore for dismantling and recycling. The onshore activities are less than 5% of the overall cost. Well plugging is about 50% of the overall cost.

Why are we doing this? Supposedly because of the environmental benefits of returning to a clean seabed. No one disputes that plugging the wells is necessary, but environmental scientists are actually not sure about the benefits of removing the topside and jackets. Some suggest that removal activities will cause more damage than good. This indicates to me that at the very least, the environmental case for decommissioning is not compelling.

If so, the taxpayer may well be providing a huge amount of money for little or no environmental benefit. It will also not create any follow-on employment or commercial activity once the decommissioning work is complete. Any money spent is dead – it generates nothing else for the nation in the longer term.

The sustainability case

From an industry viewpoint, the government’s policies for supporting decommissioning and removing infrastructure are good news. But if we look at this from the standpoint of the informed taxpayer, it is hard to see the current plans as a good deal – however well intentioned the government’s efforts are to ease industry’s transition.

This is why I would redirect the substantial capital spend required into renewable energy, be it wind or tidal or solar or whatever. The benefits for society, the environment and the economy will be substantially greater than those disputed benefits from a clean seabed.

We would have to demonstrate this with a comparative sustainability assessment of these two possible ways forward. This would have to define and compare the benefits in terms of people, profit and planet, taking into account the cost of decommissioning to the operator and taxpayer; the jobs and other socioeconomic impacts like fishing and marine transport; and the environmental footprint in terms of things like habitats, biodiversity and the impact of decommissioning.

This would produce clear differences. The renewables investment would generate substantially more sustainable jobs in areas like design, construction and operations and maintenance over the typical 25-year lifespan of a facility. Instead of just absorbing the tax-break funding, the renewable energy schemes would be generating profit and paying back to the Treasury the associated taxes during their operating lives.

The power generated by these schemes would of course be much more useful to society than the disputed benefits of a clean seabed, while there would be a big corresponding cut in carbon emissions. Given that the case for a change of policy looks so compelling, it is surprising that such a comparison never appears to have been undertaken.

If the oil and gas companies were paying the full costs of decommissioning, I would reach a different conclusion. On balance, those disputed seabed benefits would look worth having if taxpayer value was not in the equation.

But given the current arrangement, it seems wiser to let the licence holders benefit from not having to pay their share of decommissioning as a consequence of the greater good of benefiting the taxpayer. Though many service companies in the industry stand to win lucrative contracts from decommissioning and would lose out if it didn’t go ahead, this would also free up the resources of production companies for exploring and operating other fields.

If you are wondering whether the UK should alternatively scrap decommissioning and pocket the difference, it’s probably not an option. Many will recall the public and NGO outrage in the 1990s when Shell planned to abandon its Brent Spar platform.

You would defuse this kind of opposition by offering something better instead – the renewables option. Assuming the sustainability assessment stacked up, this would be a bold and courageous move by the government. It would do far more good for the UK than the £40 billion-plus outlay that is now around the corner.