Newly elected president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, has drawn comparisons worldwide to the US Republican Party presidential nominee Donald Trump: bold, outspoken, controversial, and strangely popular. Duterte has vowed to end the violent conflicts that have blighted the Philippines, stating he will open dialogues with the various insurgent groups involved within three to six months. He has also pledged to tackle corruption, illegal drugs, and criminality throughout the archipelago.

The Philippines has for years faced an insurgency in the southwest of the main southern island of Mindanao led by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) who seek independence for the Muslim Moro people from the predominantly Catholic Philippines. Filipino governments have also faced communist uprisings from the Communist Party of the Philippines and their armed wing, the New People’s Army, and the National Democratic Front. In recent years, jihadist groups declaring allegiance to the Islamic State have further complicated matters.

“Fixing Mindanao” and solving “the Moro problem”, tasks Duterte has set himself, will not be easy. But Duterte is the first president from Mindanao, and is not part of one of the political dynasties of his predecessors, based in the northern island of Luzon, where the capital is. This makes Duterte an unusual figure in Manila, but it also brings hope to many Filipinos.

The senate president and house speaker are also Mindanaoan, and while many key cabinet positions may go to Mindanaoan colleagues, Duterte has hinted that he will reserve four cabinet positions for leftist politicians, including those from the Communist Party now that they are willing to restart peace talks.

Regarding the Moro problem, Duterte has supported the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), part of the peace agreement hammered out with MILF which the previous administration failed to ratify, setting back the peace process.

Potential, but a patchy record in power

So what could Duterte’s ascent to power mean for peace in the Philippines? Arguably his Mindanaoan heritage gives him an understanding of the conflict there, as well as close relationships with many Muslims. But his statements have appeared contradictory: running on an anti-corruption and anti-elitism platform, he has also offered to pardon former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo who is currently under house arrest pending charges for electoral fraud.

While opening peace talks with the many different conflicting groups, he has also asserted that the “terrorist” Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) will be eliminated – a daring statement, as many have tried and failed before.

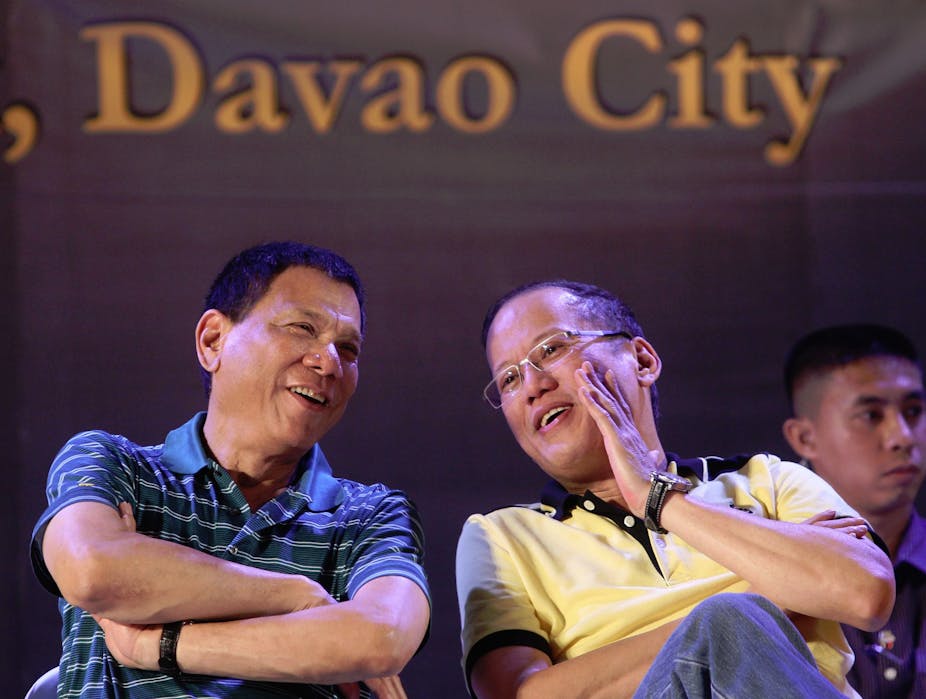

As mayor of Davao city, Duterte’s human rights record was poor, too, especially in view of his “cleansing” of criminals. This involved frequent extrajudicial killings, a policy Duterte famously promised to implement nationally.

And while Duterte vowed to pass the BBL during his presidential campaign, his views now seem to have moved instead towards implementing a federal state, which would inevitably see the MILF having to compete for power with others in the region, rather than becoming de facto rulers of their areas as under the BBL.

Maintaining an uneasy balance

Corruption in the Philippines is widespread and one of the main reasons that the protracted conflicts continue. Duterte has sworn to fight corruption, but while blaming political elites in Manila he is turning towards his own political cronies to take control of the peace process. Any change to the teams negotiating a peace may risk a loss of personal understanding and a return to square one. Having said that, if Mindanaoans play a greater role in negotiations this may avoid the mistakes of previous administrations which lacked an understanding of the region’s complex dynamics.

MILF welcomed Duterte as a presidential candidate, but his shift towards a federal state since has left them confused and frustrated. Including rival faction, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), in talks has irritated them further. Duterte is friendly with Nur Misuari, founding chair of the MNLF, but while this group signed a peace accord in 1996, factions have since taken up arms in an attempt to spoil the MILF peace agreement. Duterte is allegedly also close to the Maoist New People’s Army, which is also due to be brought to the negotiating table – but more parties to the peace process means less lucrative deals for the MILF than those they’d already negotiated.

So this is all highly ambitious, and will probably prove too great a challenge for Duterte. There are many sides to keep sweet, and waging war against “terrorists” and “criminals” – with all the risks to civilians that inevitably entails – while inviting the MNLF and the NPA to the negotiating table might well upset not only the peace agreement with the MILF, but also the established political elites in Manila and Mindanao.

To reach a peace agreement with all groups within a year seems unattainable. Despite positive rhetoric and steps in the right direction, Duterte faces many obstacles and has yet to address some of the root causes of the insurgencies: poverty, injustice, marginalisation, environmental degradation, and Moro identity.

One thing remains certain – without a clearer roadmap, lasting peace in the Philippines will remain elusive.