Anyone in Australia who has struggled with the political repercussions of a federal minority government should spare a thought for the Danes: they operate in a parliamentary system where minority government and multi-party coalitions are the norm.

The Danish political drama, Borgen, which debuts at 9:35pm on SBS1 tonight, follows the career and personal life of Birgitte Nyborg, leader of the (fictious) centrist Moderate Party.

The critically acclaimed show explores the inner workings of the statsminister’s (equivalent to the prime minister) office.

Viewers are provided with insight into Nyborg’s negotiations with multiple parties as she tries to form Denmark’s first female-led government, following her party’s better than expected election result.

Over the course of the first two seasons we see Nyborg evolve from an earnest, somewhat peripheral MP, to a strong leader forced to make sacrifices in terms of her family, friends, and even ideals, in order to ensure the continuation of her government and the delivery of key policies.

Spin doctor Kasper Juul also plays a central role. He gets the government’s message out, ensures that Nyborg looks good, and interacts with the press, including his former girlfriend Katrine Fønsmark (a TV political journalist) who conducts Leigh Sales-style interviews with politicians.

Another interesting character is Neils Erik Lund, Nyborg’s permanent secretary, who, as a state bureaucrat, has to tread carefully to remain impartial on party political matters. As the series progresses so does Lund’s behaviour towards Nyborg, other members of Cabinet, and Juul.

While Borgen has it fair share of sex, scandal and intrigue (although nowhere near the level seen in US TV), what makes it fascinating is the insight it provides into the Danish political process, including the role of the press.

By exploring the importance of getting the right message out, the difference positive press can make to a politician, and issues of privacy, especially regarding politicians’ family members, Borgen provides a somewhat unique view of everyday political processes.

Consensus style parliamentary systems

Viewers will notice a number of differences between the Danish and Australian political systems.

Political scientists divide parliamentary systems into two basic types: majoritarian, where it is normal for a single party - or two-party coalition - to win government in their own right; and consensus systems, which among other differences employ proportional representation (PR) to elect their MPs. This generally results in governments being formed by multi-party coalitions.

PR is commonly used in pluralist societies, where it is necessary to provide representation to minority groups. It is very popular in Western Europe.

Australians use a form of PR called the Single Transferable Vote, to elect the federal Senate (and most state upper houses). STV is the ability we have to vote “below the line”, where voters can choose not to vote for a party, but to preference all of the candidates seeking election. If you vote “above the line”, it is an example of Closed List PR.

Denmark uses an Open List form of PR, where voters can either vote for a party, or preference a candidate.

One of the repercussions of PR is that for the system to work, multi-member districts are required. This means that countries employing PR in their lower house don’t have local members in the same way we do.

Consensus systems are also quite different in their set up. They generally employ a hemicycle seating arrangement, rather than the confrontational government and opposition benches we see in the British Parliament at Westminster. The Australian House of Representatives is a hybrid, where the government and opposition sit opposite each other, but the seats curve around the back of the chamber, and crossbenchers sit near the middle of the curve.

There are currently 12 parties holding seats in the Danish parliament, and the minority government consists of a coalition of three parties, led by the Social Democrats.

Negotiating among multiple parties to form government can be difficult. An extreme example was recently seen in Belgium, which was without a government for over 500 days in 2010-11.

Things to look out for

One thing you’ll notice in Borgen is how little time the show spends in the parliamentary chamber. Australia is quite unusual with its almost daily question time during parliamentary sessions. Like the UK, Denmark holds question time only once a week, on a Wednesday.

Denmark has a unicameral (single house) parliament, the Folketinget, with 179 seats. 90 seats are required to form a majority government.

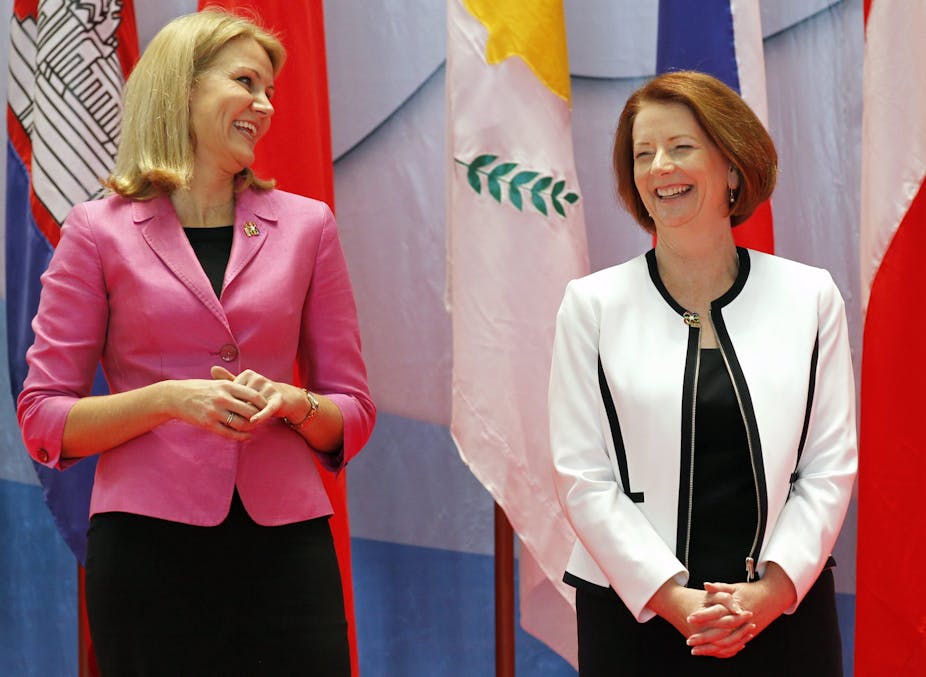

Generally minority governments rule, unless MPs form a majority against it. This is similar to a vote of confidence in the House of Representatives, where if enough of the crossbenchers withdrew their support of the Gillard government, the government would fail.

Because of its multi-party coalition government, in order to develop and pass legislation, a consensus must be gained among the ruling parties. Government MPs face a balancing act where they have to stay true to the ideals of their party, particularly if they went to the electorate with a particular platform, and yet ensure essential legislation (such as the budget) is passed. This pressure is particularly intense for members of cabinet.

Failure to successfully pass legislation can lead to a coalition collapsing, and either a new government being formed with a different set of parties, or elections being necessary. This is the reason why Italy had so many governments between 1945 and the 1990s. While the [Christian Democracy](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_Democracy_(Italy) party led almost all of the governments throughout 1944-1992, their coalition partners were on a revolving door.

Within Denmark, this pressure makes the PM’s opening speech a major test for any government. The speech, given during the first sitting of the sessional year, outlines the current state of Denmark and the government’s planned measures. A general debate, which can last for a number of days, takes place on the basis of this outline. Failure to gain the support of a majority of MPs for the plan can lead to the downfall of the government.

To help guarantee the longevity of proposed reforms, the government may try to form an informal “grand coalition” involving both government and non-government parties agreeing to support key legislation. Nyborg’s attempt to operate outside traditional bloc-voting lines in the second season is one of the highlights of Borgen.

The Danish parliament uses an electronic form of voting. Votes can either be a basic count, or an actual roll-call vote where the response of individual members is recorded publicly.

Ministers can be appointed to the cabinet from outside the legislature as a result of their expertise in a particular field. Non-elected ministers are not entitled to vote during parliamentary sessions.

Voting in elections is not compulsory in Denmark, but there is a high level of voter turnout, at around 85%.

Finally, the show provides an interesting insight into Denmark’s workplace relations legislation. It appears that being prime minister doesn’t guarantee you the right to a competent assistant or the ability to demand a new one!

Must watch TV

Despite all of the differences between our two political systems, one of the best features of Borgen is its selection of timely policy issues that resonate equally well in Australia.

The attempt of Nyborg to hold true to her beliefs and yet run an effective government makes Borgen compelling viewing.