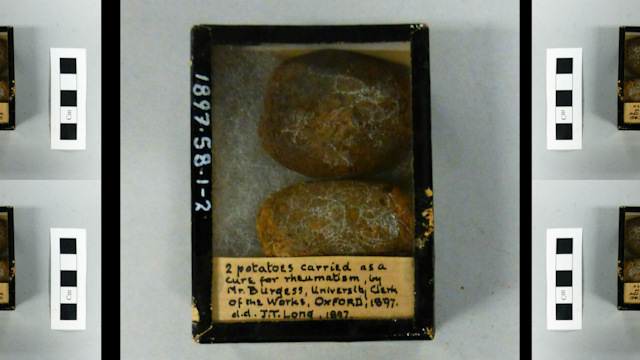

In 1897, one Mr Burgess, the Clerk of Works at Oxford University, donated two shrivelled potatoes to the Pitt Rivers Museum. He usually kept them in his pockets. They were the ultimate “jacket” potatoes.

The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford is dedicated to categorising and displaying a “democracy of objects” not according to time or nation, but according to human usage. Since the potato is fairly ubiquitous in human culture, it means there are many in the museum’s collection.

In addition to Burgess’s donation, 11 other wrinkled specimens are catalogued in the museum’s collections, and are neatly labelled. The names of the previous owners are usually not identified because most of the potatoes were stolen before they were donated.

But why would someone would want to steal a wrinkly potato? The answer is these were not just any purloined spuds. They were medical charms thought to be cures for rheumatism – and if they were stolen, they were thought to be even more effective.

In the Victorian era, and for centuries before, a variety of vegetables were carried whole, or pulverised and put into bags to hang around the neck in the hopes of warding off or curing illness.

Plants as drugs

Before modern pharmaceuticals, most materia medica (substances used in medical practice, or drugs) were herbal. Their usage was described in books by the ancient Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides (40-70 AD) and in Pliny’s Natural History (1st century AD), an encyclopaedia written in ancient Rome. These books from the ancient world continued to be reference guides throughout the Renaissance.

In his book Pliny described the usefulness of plants such as the mandrake root, which was thought to resemble a human figure complete with what was known as “the virile members”. The root was made into amulets to be worn to promote fertility and in love magic. Using it in this way, is also referred to in the Song of Solomon in the Bible.

Because the root contained hallucinogenic and narcotic active ingredients, it was also used as an anaesthetic and to relieve the pain of arthritis. By the 16th century, herbalist John Gerard’s Herball or General Historie of Plants related the legend that if one pulled it from the ground, the root would scream, killing anyone who heard it (possibly a result of a couple of bad trips).

Illnesses caused by the planets

Paracelsus, a 16th-century Swiss doctor, elaborated upon such theories, claiming each plant had what was called a “signature” or sign of its medical application resembling the part of the body or ailment that it could cure.

For instance, lentils and rapeseed were thought sympathetically to cure smallpox because the seeds were similar to the pox pustules. The appropriate herbs, pulses, seeds or vegetables were bundled and worn about the neck to affect the cure.

Other plants, such as the sunflower, were thought to promote the hot and dry characteristics of the sun, good to warm you if you suffered from a cold.

Plant therapy was also linked to the use of astrology in early medicine. The planets were thought to control the fluids or “humors” in the body (black bile, blood, yellow bile, and phlegm), all of which had to be kept in careful balance to promote health. An imbalance was believed to be cured by bleeding or by the ingestion of an herbal remedy, or in some cases, wearing of the appropriate plant amulet.

Diseases caused by a particular planet could be healed by a herb of the opposing planet. For example, lunar diseases were considered to produce an abundance of cold and moist humours, as the Moon controlled the waters in the tides.

Diseases that produced phlegm and caused sneezing like the common cold, or those that produced fluid-filled tumours, such as scrofula, were therefore considered governed by the Moon. These lunar diseases could be cured by means of solar herbs or tinctures, which were hot and drying as sunbeams. Hence the sunflower cure. Lettuce which was watery was to be avoided.

But what of our potato and its connection to rheumatism?

There is a poison, called solanine, present in green potatoes and potato eyes (the root-like sprouts). Solanine is chemically closely related to another poison tropane alkaloid, named atropine in deadly nightshade. In fact, the potato is called a nightshade vegetable.

Atropine cream in the Victorian era, sometimes in combination with morphine, was applied to “relieve the pain of rheumatism, sciatica and neuralgia”. Although there proved to be no scientific basis for this, atropine is used in contemporary medicine to dilate the pupils or to elevate heartbeats in a medical emergency.

There were several cases of murder involving putting higher levels of atropine in tea or in a gin and tonic, its bitter taste disguised by the booze.

As to why the potatoes had to be stolen to cure rheumatism, we still don’t quite know but it certainly adds to their charm.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.