Once upon a time, in the ancient Near East, there was a beautiful queen.

Scribes wrote of her lovely form, her regal majesty and her fierce bravery. The people honored her in lavish celebrations marked by debauchery. She was linked to the morning star, and her name was “Ishtar” – or “Esther,” as she was called in Hebrew.

This is the story that inspires the Jewish holiday of Purim, which begins this year on the evening of March 23. Across the world, Jews retell the story of Queen Esther in lavish spectacles, called Purim spiels, that feature costumes, jokes, satire, noisemakers and food and wine.

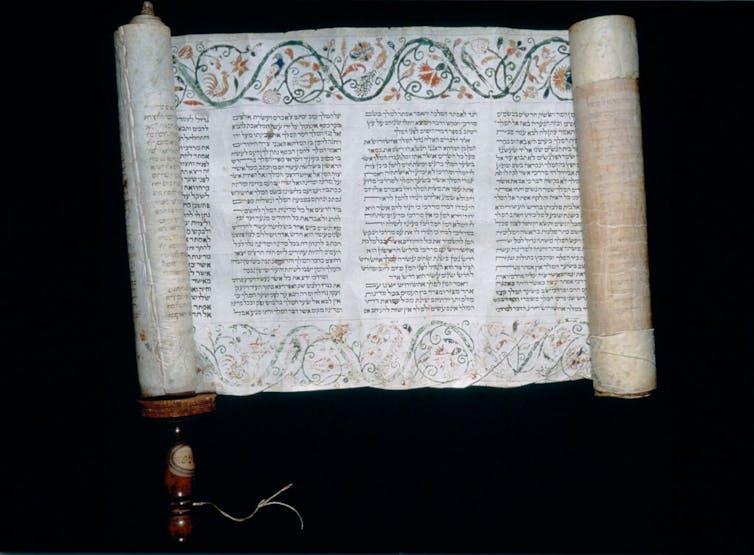

Purim is the only celebration in Judaism with an entire biblical book about its origins. The Book of Esther tells how she and her pious cousin, Mordecai, defeated the scheming Haman, a powerful royal adviser, thereby saving the Jewish people from annihilation.

Yet among researchers, the actual origins of the holiday – and of Esther herself – are still hotly contested. Few scholars interpret Esther’s story as a record of historical events, and they note a number of oddities surrounding the book. The text, sometimes called the Megillah, contains no mention of God, or of religious activities such as prayer or sacrifice; its narrative is colorful and suggestive.

When archaeologists began to dig up cuneiform texts in the 19th century, a further peculiarity emerged: Esther and her cousin Mordecai shared names with Ishtar and her cousin Marduk, two of the most prominent deities in ancient Mesopotamia. Ishtar, like Esther, was a divine queen associated with both eroticism and battle. Marduk, like Mordecai, overcame a deadly enemy and celebrated his triumph with a banquet. Moreover, the name Purim seems to derive from the Babylonian word “pûru” – a “lot” in both the senses of “portion” and “fortunetelling dice.”

Earlier scholars of those cuneiform texts concluded that the Book of Esther was retelling a Babylonian myth about Ishtar and Marduk. No such myth has been found to date, however, leading to an apparent historical dead end.

When I learned about these connections as a young biblical scholar, a modern parallel immediately came to mind: the genre of fan fiction.

Fanfic, then and now

In fan fiction, amateur writers create stories based on the characters and imaginative worlds of popular media.

Sites such as the Archive of Our Own, FanFiction.net and Wattpad host millions of “fics,” from short sketches to novel-length epics. The popularity of these stories has extended beyond the internet: “Fifty Shades of Grey” was a fic of the teen series “Twilight,” while the bestselling novel “The Love Hypothesis” began as a story about characters from “Star Wars.”

Fan fiction studies has become an established corner of academia: studying these texts, their creators and the factors that influence them.

I am not the first scholar to wonder whether ancient texts were the fan fiction of their time. Scholars and fans alike have noted the way that the Aeneid builds upon Homer’s compositions, for example, and John Milton’s epic “Paradise Lost” mines the tales of the Bible.

I believe it makes sense to think of Esther, too, as the ancient equivalent of today’s fan fiction: a tale of familiar characters, re-imagined and repurposed to reflect the identities of their creators.

To begin, Esther and Ishtar had more in common than just their name. In fact, everything in my first paragraph describes them both, from the raucous celebrations held in their names to their legendary beauty. The author of the Book of Esther seems to have been describing a character already familiar to readers, just like a modern fan fiction writer does.

This comparison is not hindered by the fact that the plot of Esther did not derive from a known Mesopotamian myth; plenty of “alternate universe” fics tell new stories in new settings, using the change of scenery to reveal new facets of their beloved characters.

Nor does the divide between Mesopotamian polytheism and Jewish monotheism pose a problem. For many authors, fanfic provides an opportunity to transform and critique its source text, adding elements that were glaringly absent from the original, such as queer relationships.

In short, thinking about the story of Esther as ancient “fanfic” could explain the striking parallels between her character and Ishtar. But the implications of this framework are more than simply academic. Calling Esther fan fiction can teach modern readers something about the celebration of Purim – and about storytelling itself.

Writing ourselves into stories

The first lesson is that, from ancient Jewish scribes to modern teenage girls, people have been rewriting other people’s stories to reflect their own reality and identities.

Today, a fanfic author might compose a saga about how a girl like her won hearts and saved lives in male-dominated Middle-earth, the world of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” series. Back in ancient Babylon, Jewish scribes might have re-imagined a popular goddess as a Jewish heroine. Transformative writing is empowering and defiant, then as now.

The second lesson is that carnival and queerness and joy are built into ancient scripture; they are no modern development. Ishtar was a gender-fluid queen who declared, “I am a woman (but) verily I am an exuberant man.” Her followers included “assinnu” and “kurgarru,” ranks of Mesopotamian priests who were famous for transgressing gender norms.

It should thus come as no surprise that Esther is a story that names and elevates a number of eunuch characters, ascribes feminine and nonbinary traits to the heroic Mordecai and imagines its heroine as sexual and daring. Purim’s long-standing tradition of cross-dressing and flamboyant costumes has a rich history.

Likewise, fan fiction is a deeply queer practice. A disproportionate number of stories address gender and sexuality, and its creators are themselves disproportionately LGBTQ+.

The third lesson is one that I strive to teach all my students: Scripture can be both relatable and startling when we look at it through fresh eyes.

The Bible instructs Jews to retell the story of Esther each Purim. But by creating themed Purim spiels each year, drawing on sources from Motown to Moana, Jewish congregations clothe the familiar plot in exciting new garb.

Thinking about biblical stories as fan fiction invites readers today to imagine the ancient scribes as “fans,” brimming with emotional reactions and strong opinions. The Bible is a diverse library of texts created in manifold times and contexts, and its authors were passionately invested in the stories they told and retold – just like modern amateur authors.

This Purim, I invite you to approach the Bible’s tales as the result of a dynamic process, a panoply of voices that each sought to influence their tradition by adding their own words to it. In the hands of fan fiction writers and Purim spiel creators, that process continues today.