Australia currently has a trade deficit, where what we import outweighs what we export. Amid the ongoing debate on the benefits of globalised trade and jobs, a Trump style border adjustment tax could be one solution.

It’s commonly assumed that rising imports are a drag on the economy, as they subtract from the GDP equation. The counterargument is that imports can improve firm productivity and export competitiveness.

In January, Australia’s trade surplus surprisingly shrunk by 61% on December’s, because exports went down 3% and imports jumped 4%.

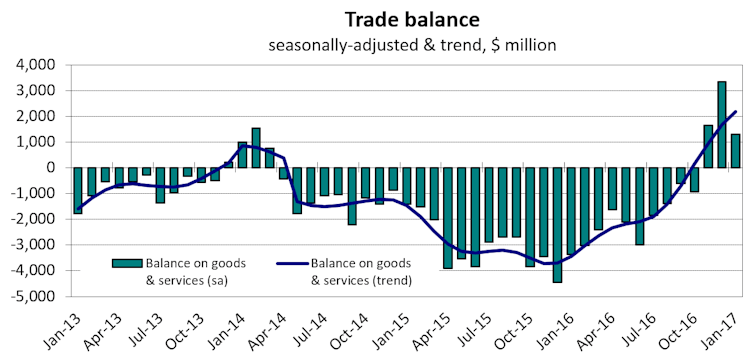

This is bringing Australia’s trade balance back to normal, into negative territory. In fact, in the past four years, our seasonally adjusted trade balance was positive for only seven months.

The border adjustment tax, a current proposal from the Trump administration, has been dubbed “Trump’s virtual wall”. It’s based on a simple idea to impose a flat tax rate on imports, and to grant corresponding tax rebates on exports.

The idea of using border tax instruments to improve trade competitiveness dates back to John Maynard Keynes’ Macmillan Report to the British Parliament in 1931.

Following Trump’s plan, a recent wave of academic papers on international taxation and monetary issues, as well as public policy have revived Keynes’ trade perspective on border adjustment tax.

How it would work

Border adjustment measures are normally used under a value added tax, like the GST, which applies to all consumption. It also excludes any goods or services that are produced domestically, but consumed abroad.

Trump’s blueprint tax reform proposes converting the current corporate income tax into what is called a “destination-based cash flow tax”. The key point of this new tax is that it would combine the fiscal calculation of cash flow (like with income tax) and border adjustment (as what happens with the GST).

As its name implies, with border adjustment a destination-based cash flow tax shifts taxation from the country of production to the country of sale.

On the surface, implementing the cash flow border adjustment tax is a no-brainer for countries with a trade deficit. It raises government revenue and boosts jobs in the export-driven industries, which tend to concentrate in the embattled manufacturing sector.

For instance, if Australia slapped a blanket 20% cash flow border adjustment tax in the last financial year, which registered a trade deficit of about A$37 billion, the Treasury would have raised A$7.4 billion at the net of tax breaks for exports.

In a relatively high-tax jurisdiction such as Australia, a border adjustment tax on cash flow would be an efficient way to raise revenue from trade between international firms. It would reduce the incentive of multinational corporations to shift profits and jobs to lower-tax jurisdictions.

However, some economists estimate that border adjustment provisions eventually result in stronger currencies and higher interest rates. So the cash flow border adjustment tax would only work on the assumption that boosted exports would promptly and fully offset higher interest and exchange rates, as well as possible trade retaliations.

It’s also uncertain this type of tax would be fully compliant with the rules of the World Trade Organization, which normally allows for border adjustments only through indirect taxes (for example on transactions, such as sales and payroll), and not so indisputably through direct taxes on individuals or businesses.

Technically speaking, border adjustment tax measures do not distort trade, as long as the import tax and export rebate offset each other. These measures also don’t discriminate between industrial sectors or trading partners.

The Australian government should closely monitor whether the cash flow border adjustment tax works in the US, without too much disruption in monetary levels and global value chains. Australia shares similar economic characteristics with the US economy in respect to relatively high corporate tax rates, a substantial trade deficit, and declining employment levels in the manufacturing sector. So the tax could work here.