The scene, a large smoke-filled room in Baghdad 40 years ago on July 22 1979. About a hundred unsuspecting Ba'athist party members sat listening to their newly installed president, Saddam Hussein, denouncing a conspiracy against him.

Suddenly a man was brought before the conference, bearing the marks of torture and the vacant expression of a broken mind and soul. Muhyi Adbek Hussein, one of the senior Ba’athist leaders, proceeded to confess his role in a plot to overthrow Saddam’s new regime and name his alleged co-conspirators. One by one, 50 names were called out, each man escorted from the room by uniformed guards.

It was a chilling sight. The remaining members, now visibly afraid, started chanting vociferous allegiance to Saddam in the hope of avoiding the fate of their colleagues. These survivors of his brutal crackdown were then handed guns, and ordered to execute their fellow Ba’athist colleagues, making them complicit in their leader’s crimes. Journalist Christopher Hitchens compared the shocking scene to the Night of the Long Knives in Nazi Germany, when Hitler ordered a similar purge of his own perceived opponents in 1934.

A totalitarian regime

Though this infamous party conference happened 40 years ago, it remains one of the most shocking episodes of violence in Iraq’s history, marking the beginning of Saddam’s 24 years of absolute power. There were comparisons with Joseph Stalin, due to the way he moulded the Iraqi political structure into a one-party system, ruled by a small elite comprising close friends and family. But his penchant for public violence would remain a notable difference.

Another discrepancy was reflected in the degree of control over each country’s economy. While Stalin managed to impose a fully centralised economy and forced industrialisation, Saddam opted for a mixed economy which allowed private possession of land and businesses.

Even though the authoritarian Iraqi government was liable for establishing the prices of goods as well as making decisions regarding oil, around 50% of the Iraqi GDP was privately generated, demonstrating the less totalitarian approach of the regime in this respect.

Political implications

The purge shaped Saddam’s image as a ruthless dictator who would not tolerate any form of dissent. His Ba’ath ideology of Arab unity, freedom and socialism, and the struggle against imperialism and Zionism was nothing but a sham political agenda. He soon instilled a climate of fear and perpetrated torture, kidnapping and mass murder, as well as crimes against humanity and war crimes prosecuted under the International Criminal Court.

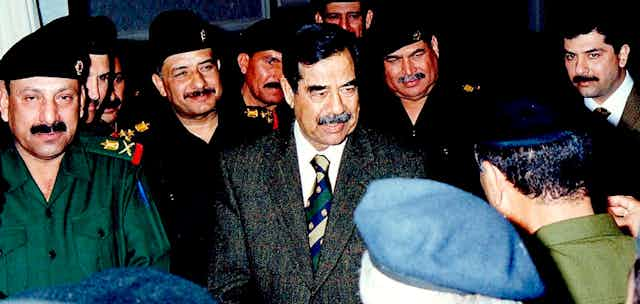

It also established Iraq as an emerging regional power, disrupting the Middle East’s political status quo. Soon Saddam would be known to his people by many names – the Anointed One, Glorious Leader, Chairman of the Revolutionary Council, Field Marshal of the Armies. He wore a general’s uniform, decorated with medals awarded by himself, even though he had never served in the army.

Envisaging Iraq as a great regional power Saddam frequently engaged in military conflicts, the first being the Iran-Iraq war which took place in the early 1980s. Iraq considered the war against Iran an opportunity to settle longstanding disputes over its borders, such as the annexation of the oil rich province Khuzestan.

Saddam Hussein also perceived Iran as a threat to the survival of his regime, as the neighbouring country was considered a great source of inspiration to the Shi’a revolutionaries of Iraq. Shi’a Muslims accounted for around 60% of Iraq’s 25m people, yet were ruled and oppressed by the Sunni minority regime led by Saddam. In contrast, Iran had a Shi’a majority with Shi’a rulers.

This led to close links between Iraqi Shi’a and Iran, whose new leader Ayatollah Khomeini hoped they would rise up and overthrow Saddam’s perilous regime. The war ended in a stalemate after eight years with both countries claiming victory. Saddam continued his quest for power and prestige by invading Kuwait in 1990. The invasion had major consequences, bringing immediate economic sanctions upon Iraq from the UN Security Council (UNSC) and the commencement of the UNSC Iraqi disarmament.

End of the Saddam era

The imposed economic sanctions lasted until the end of Saddam’s regime in 2003, dramatically weakening his position and the Ba’ath party’s grip on Iraq. Although his regime was in its last stages by the late 1990s, the US government chose to launch “a pre-emptive, self-defence war” against Iraq, aiming to overthrow him.

With the 2003 execution of Saddam, the chapter of one of the most authoritarian regimes in recent history was closed, ending the fiction – even as the noose placed around his neck – that he remained president of Iraq. The authoritarian despot had oppressed his country for quarter of a century, unleashing devastating regional wars and reducing his once promising, oil-rich nation to a stifled police state.

His insatiable desire for power made Saddam sacrifice his own people, inciting the ire of neighbouring states and the international community. Although Saddam and the Ba’athist Party used various methods of control, from indoctrination and surveillance to brutal repression, torture and mass killings, Saddam’s regime was never fully successful, demonstrated by the Shi’a uprisings in 1991 and the Kurdish struggle for independence.

Even though Saddam’s tyrannical rule came to an end 16 years ago, the new Iraqi democracy has barely kept a grip on power as decades of unresolved religious ethnic and social division have curdled into full-scale insurgency and sectarian bloodbath, killing hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.

The unity of post-Saddam Iraq’s geography is yet to be reflected in its fractious society. The memory of sectarian conflict is ever present, still claiming the lives of Iraqis every month. Today Iraq is a fragile state where the Shi’a abuse power, the Saudis destabilise the area to advance their own interests, and the Iranians pull the strings in Baghdad. Ultimately, post-Saddam hopes of freedoms and basic human rights have failed to materialise, that democratic, stable and fair society still elusive.