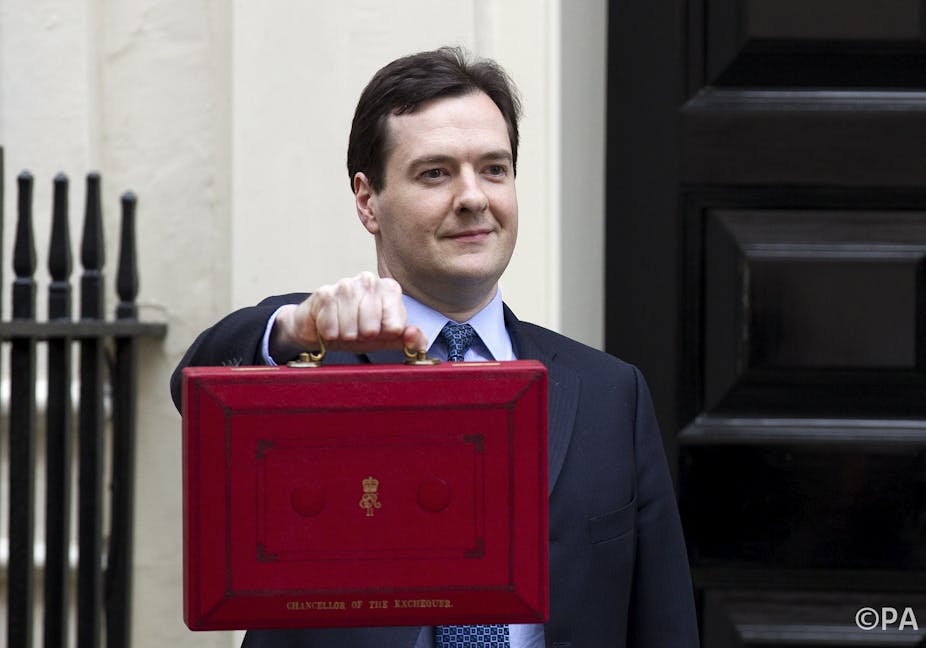

Who lives at Number Ten Downing Street? The answer is of course… George Osborne. While his official residence may be next door at Number Eleven, it is he and not David Cameron who lives in the flat above the Prime Minister’s place. Perhaps this should come as no surprise. After all, Osborne is routinely described as “that most political of chancellors”. Everything he does and says is dedicated, say friends and foes alike, not just to nursing the nation’s economy back to health but to ensuring that the Conservatives are returned to power at the general election next year.

But is Osborne really so very different to those who have occupied his post in the past? It’s not as if, prior to his doing it, the job tended to go to economists or accountants. Chancellors have always been politicians and they have therefore always been political. Yes, they have tried do their best by the British economy but they have been equally set on winning elections too. In any case, the two things are normally seen as synonymous: get the economy right and the voters will reward you and your party, right?

Wrong. Looking back over the decades since the World War II, it seems as though the key to success lies not so much in getting the economy right as getting the timing right. Chancellors, particularly those who write their memoirs, might like to give the impression that they were locked in battle with a prime minister whose only concern was to get his or her government through the next election and hang the consequences. But, more often than not, the arguments between Number Ten and Number Eleven are about how best to align the electoral and the business cycle rather than about what is necessarily best for the country.

True, concerns about one’s legacy play a part. Rab Butler’s election-winning generosity in 1955 and Reggie Maudling’s “dash for growth” nearly a decade later left both men nursing sore heads and a reputational hit which left the top job out of their reach.

The economist next door

Things also depend quite a lot on the prime minister a chancellor serves.

Those who know a lot – or think they know a lot – about economics are the trickiest. Maudling had replaced Selwyn Lloyd who had been continually under pressure from Macmillan (himself a former chancellor) to go for growth. Jim Callaghan, who replaced Maudling when Labour won in 1964, had to put up with a good deal of interference from Harold Wilson, an economist by profession. He got the party through the 1966 election largely by blaming the Tories for his dire inheritance only to experience the humiliation of devaluation in 1967. That it was Wilson’s humiliation too meant Roy Jenkins – probably a better match for Wilson intellectually anyway – had a much freer hand than his unfortunate predecessor. Not that it did him much good in the end; it was Callaghan, not Jenkins, who succeeded Wilson as prime minister in 1975.

Jenkins is often cited as the shining example of a chancellor who took tough decisions, overseeing what at the time anyway passed for a brutal package of spending cuts and insisting on an export- rather than a consumer-led recovery. His reputation among commentators (although not among his colleagues) was only enhanced when, in 1970, he supposedly refused to buy an election by delivering the usual pre-election giveaway budget.

The reality was rather different. For one thing, Jenkins was not expecting Wilson to call the election as early as he did, so the slow-burn, pro-growth measures he snuck into his budget did not have sufficient time to work. For another, his decision not to go hell-for-leather was essentially a bet that Labour would be given the credit for acting responsibly by a grateful electorate.

Trusting voters to reward actual rather than easy virtue is rarely a good idea – particularly if the economy upon which a chancellor is making his pitch seems stronger in the abstract than it does in the particular. This, as Osborne (a history buff) will no doubt be painfully aware, was very much the case for Jenkins. The statistics were, for the most part, impressive; but two years during which prices had seemed to be rising faster than earnings meant that far too many voters were still feeling the pain rather than looking forward to the gain.

That said, there are plenty of examples of chancellors who have ignored the proverbial lessons of history and ended up making the same mistakes, either losing elections or shredding their own reputations or, in some cases, both. Tony Barber allowed himself to be bullied by Ted Heath – as dominant a prime minister in his day as Wilson before him and Thatcher after him – into a Maudling-style dash for growth, only to be forced into choking off an unsustainable (and now eponymous) boom just as the prime minister gambled everything (and lost) on a snap election in February 1974.

Slamming on the brakes

Dennis Healey, Callaghan’s chancellor, got a grip on spending and inflation (with the help of the IMF). Until, that is, his boss surprised everyone (including him) by not going to the country in the autumn of 1978 – a move which required another round of pay restraint from the unions that Healey simply couldn’t deliver. And after Geoffrey Howe – surely the exception that proves the rule – did the business for both the economy and Margaret Thatcher in 1983, her second chancellor, Nigel Lawson, stepped far too heavily on the accelerator in 1987 and ended up having to slam on the brakes way too hard before resigning (supposedly in protest at prime ministerial interference).

Ken Clarke, will go down in history along with Roy Jenkins as a chancellor who did right by the economy but, by balancing the books and pursuing a sustainable rather than a consumer-led recovery, helped lose his party the election. Clarke, like Jenkins, calculated that some sort of dash for growth would have backfired politically as well as economically – and, given the Tories’ loss of credibility after the ERM debacle, he was probably right. Like Jenkins, he must have hoped - in vain, as it turned out - that he’d get at least a little gratitude from voters. Deep down, however, one suspects he knew that no amount of give-aways and goodies would be enough to beat Blair and Brown, and so decided that, if defeat were to come, it would be an honourable one.

The same perhaps was true of Alistair Darling. And unlike Clarke, he had to spend almost as much of his time fighting off the man next door as he did fighting off a domestic and global depression. Gordon Brown, after ten years as one of the most powerful and electorally successful chancellors this country has ever seen, simply wasn’t prepared to let go, but Darling somehow found the strength to stick to his guns. Had he not done so, and simply buckled in the face of Brown’s delusionary attempt to draw the old dividing lines between “Tory cuts” and “Labour investment”, his party may have gone down to an even bigger (and infinitely more dishonourable) defeat than it eventually did in 2010.

George Osborne, one suspects, is not a good loser – at least not while he feels he has a chance of winning. Clearly he still does. Even economists whose hearts beat on the right know that the growth he can finally boast about has been achieved by a combination of phenomenally cheap money, a below-the-radar relaxation of austerity and, worse, a reliance on the housing market and on consumption and household indebtedness that will store up trouble in the future.

But Osborne has several things going for him that some of his predecessors did not.

First, barring a complete breakdown of relations with the Lib Dems, he knows when the election will be, making the thorny issue of timing ever so slightly less thorny. Second, he is working alongside rather than for or (as was sometimes the case with Gordon Brown) against his boss – and his boss knows even less about the economy than he does. Third, as a politician who would one day like to occupy the downstairs as well as the upstairs of Number Ten, he knows chancellors who preside over an honourable defeat never recover to win the leadership of their party. The “Catch-22”, however, is that chancellors who take the less honourable route hardly ever do either.