The release of the Panama papers is yet to reach its endgame, but there are some clear truths we can take from it. People or businesses who don’t pay their taxes – whether deliberately or through ignorance – undermine state revenues. They also distort competition by putting the non-compliant at an advantage, and they increase inequality as it is the better off who more often tend to escape their obligations.

When governments look around for easy savings or boosts to revenue, they might baulk at raising taxes but there is a good economic reason for improving how existing taxes are collected. The measures put into play by European leaders since the leak from Latin American law firm Mossack Fonseca have accentuated both the importance of cooperation, as well as the potential value to nations from innovative action.

The last few weeks have reignited efforts by politicians to enhance tax compliance and make it a central policy concern in many countries. And as government departments struggle to get a grip, every now and then, the idea of privatising the collection system itself is mooted.

The tax gap

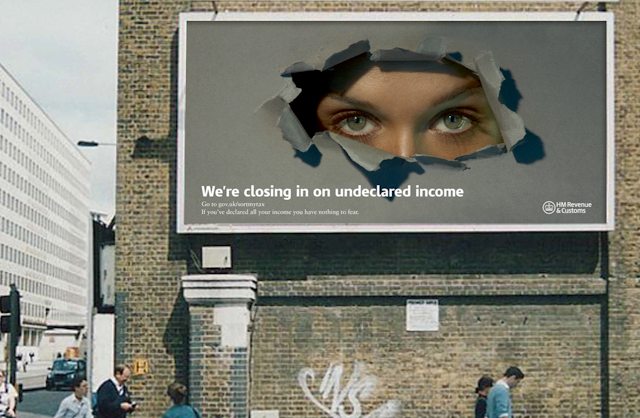

Much like other government departments, tax administrations in many countries have faced public demands for more efficient service delivery and greater accountability. Driving much of this is the existence of the “tax gap” – the difference between actual tax collected and the potential collection level if we all paid exactly what we owe. The more weak and inefficient a country’s tax administration system, naturally, the bigger the “tax gap” is.

Offshore avoidance and evasion is hard to factor in, but even so the numbers are significant. For the UK in the financial year 2013-2014, the “tax gap” was estimated by the HMRC to be £34 billion, which is roughly 6.4% of total tax liabilities. The self-employment tax gap alone over 2010-2012 was at 19.3%.

For other countries, with less efficient tax administrations, the tax gap is certain to be higher. In South Africa it is estimated at 15-30% of tax revenues. If the extent of corruption is a good proxy for the “tax gap” the picture is significantly more troublesome in sub-Saharan Africa.

It’s easy to see, then, why reform of tax administrations has become central to the policy agenda. Since the economic crisis, countries have struggled to tackle public deficits, restore stability and address high administrative and compliance costs. The focus of efforts by government agencies has been on the modernisation of the departments which collect revenue and their independence from other government agencies.

Business case

This has clear echoes of a more corporate approach. It is all about making tax collection work through flexibility in the management of budget and human resources. So tax officials get well-identified objectives (including the appropriate design of tax enforcement policies), performance standards (appropriately supported by the required resources) and incentivising mechanisms (including performance rewards).

Tax administrations which are run pretty much independently of the government, the argument goes, will increase performance by these means. It should also maintain accountability and transparency. But why not go the whole way? If a revenue administration is inefficient, perhaps efficiency could improve if some or all of their activities are outsourced to the private sector, under monitoring by the government. Is outsourcing of collection a more efficient social institution than a tax administration run by a government?

Recent examples of outsourcing arrangements across a number of functions suggest some resurgence of interest in the concept. No doubt, there is appeal in allowing administratively inefficient governments to minimise the cost of collection of tax revenues, thereby providing much-needed savings which, in principle, can be passed on to consumers.

Different countries outsource different functions, but some common categories emerge. The provision of IT infrastructure has been farmed out in Australia, New Zealand and the UK; the collection and processing of tax payments has taken place through banks and post offices in Argentina, Australia, New Zealand, Greece, Sweden and the US. Less common is outsourcing of data processing operations (in Brazil, Denmark, Ireland and Mexico) and enforced collection of tax debts (in Australia, Ireland, Italy, Singapore and the UK).

Market stalls

There is a good reason that some areas are favoured over others from an economics point of view. Efficiency of markets depends on the voluntary participation of the parties in a transaction (sellers and buyers), but with tax collection, as Al Capone might testify, this is not always the case. Indeed, the presence of evasion suggests otherwise: tax transactions (being compulsory, unrequited and non-repayable) are not voluntary. Importantly, too, the process of tax collection requires the safeguarding of taxpayers’ rights and protection, in particular from overzealous tax collectors.

This requires monitoring, a function that only the state can perform – and one that requires considerable resources. Importantly, too, conflicts of interest might also arise, as collection requires private agents to have access to confidentially sensitive information on taxpayers that can be used to obtain an unfair advantage. It is, therefore, difficult to argue that one can rely on the market to generate an efficient outcome in collection.

Can we, therefore, rely on outsourcing to improve efficiency, while maintaining fairness in tax collection activities? While outsourcing might be appealing, the scope for privatising the core functions of tax administration looks limited. Secondary functions or low-scale collection of lower tax debts, might be feasible. Some early steps towards this are taken in some countries.

In Australia, for instance, handing collectable debt to external collection agencies was trialled in 2006 and implemented a year later. Early results show some promise. They indicate that there is indeed some scope to improve efficiency through outsourcing certain aspects of the tax system, but it would be a brave, and possibly foolish, government which ignored the market obstacles which mean a wholesale privatisation is fraught with dangers and contradictions.