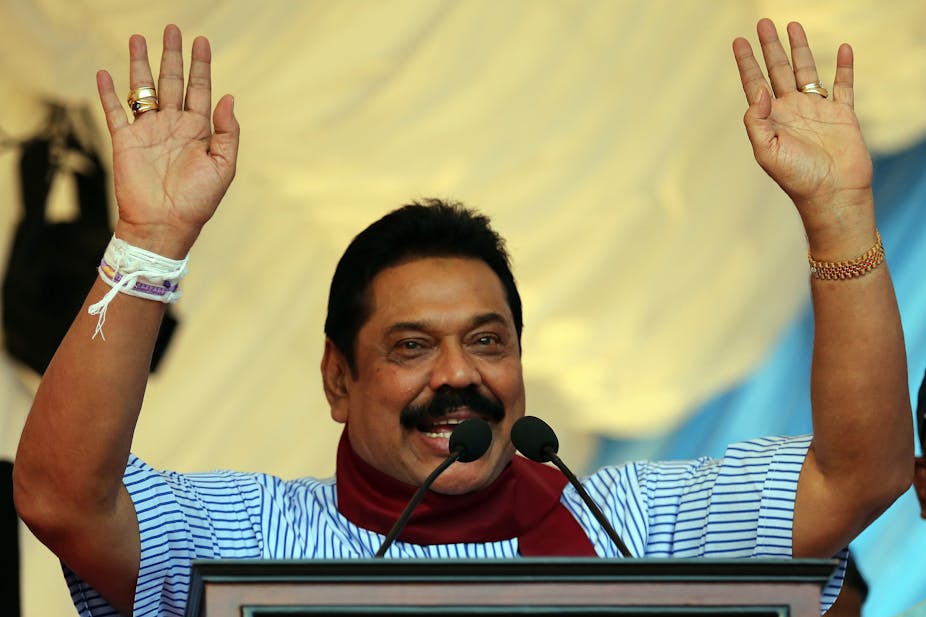

Sri Lanka’s president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, has been defeated in the country’s historic presidential elections. Sri Lankans are shocked at the scale and manner of Rajapaksa’s defeat, which has brought his tenure to an abrupt halt after nine highly controversial years.

When Rajapaksa called the election nearly two years early, he did so with the expectation that he would win comfortably. While he was concerned that support for his ruling coalition was rapidly waning, he took comfort in the knowledge that the opposition United National Party (UNP) remained divided, and seemed incapable of fielding a candidate who could rival the president’s appeal to the Sinahala majority.

Until the night of January 8, few were confident of an opposition victory. That was reflected in the prematurely printed headlines of daily newspapers: the January 9 edition of the state-owned English-language newspaper, The Daily News, boldly pronounced that “there is hardly any doubt about the fact that the incumbent … is almost guaranteed a comfortable victory.”

Rajapaksa’s personal popularity has declined steadily in recent years due to growing concerns about corruption and nepotism, mounting frustration and alienation from minority groups, and a failure to address everyday economic issues such as the high cost of living. His reign saw the defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) rebels in 2009, and impressive post-war economic growth rates.

But it was also marked by a growing concentration of power in the hands of the president and his close family members and the undermining of Sri Lanka’s democratic institutions.

Another way

The pivotal moment in the election came when Maithripala Sirisena, Rajapaksa’s health minister, put himself forward to stand as the common opposition candidate in November, giving the president’s opponents an unexpected boost.

The now-victorious Sirisena appeals to the same core nationalist voters as Rajapaksa, but he was also able to draw support from a grand coalition united by opposition to the Rajapaksa regime.

Sirisena was backed by parties and prominent figures spanning the political spectrum, including Chandrika Kumaratunga, a former president, the UNP, several smaller parties (including the hardline Buddhist JHU), and leaders from the Tamil and Muslim minorities. His campaign was also accompanied by a series of crossovers from government ministers and MPs.

Reversing the slide

On the face of it, the election marks a major turning point in Sri Lanka’s political history. This is the first time an incumbent president has been defeated at the polls and had Rajapaksa won as expected, he would have become Sri Lanka’s first three-term president. He abolished the two-term limit in 2010 and took control of the constitutional council, which had independent responsibility for making key appointments in the civil service and government commissions. His presidency also saw widespread suppression of government critics, human rights violations, and the erosion of the judiciary’s independence.

Sirisena said he was unable to stand with a leader who had plundered the country, government, and national wealth, and he stood on a promise to reverse the slide towards authoritarianism by abolishing the executive presidency and restoring constitutional checks on the president’s power.

Although the campaign was not free from violence – a local monitoring body, the Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV), documented a total of 420 incidents of the course of the campaign – fears of an escalation on polling day proved unfounded. Similarly, predictions that the president might use the state machinery to deliver a fraudulent result also turned out to be wide of the mark.

The scale of the swing towards Sirisena seems to have ruled out any major foul play and convinced Rajapaksa that a dignified retreat from power was the most judicious option.

Trouble ahead

While many in Sri Lanka are rejoicing at Sirisena’s victory, major difficulties lie ahead. The new president will quickly embark on an ambitious 100-day reform agenda which plans to conclude with the dissolution of parliament in April. He will also face the huge challenge of holding together his unwieldy coalition for long enough to push through ambitious constitutional reforms. If and when a new parliamentary system is introduced, these problems will only intensify.

Sirisena’s allies remain sharply divided on a range of issues, not least those that continue to face the minority Tamil and Muslim communities. The new president has neglected minority demands in the campaign, ruling out any further devolution to Tamil and Muslim-majority provinces and vowing to prevent any international investigation into alleged war crimes committed by leading government figures during the final stages of the civil war in 2009, which cost the lives of tens of thousands – especially in its bloody final phase, when Sirisena himself was acting defence minister.

The Tamil National Alliance, the leading Tamil party, reluctantly backed Sirisena in the hopes of opening political space, resisting Rajapaksa’s call for them to side with “the known devil”. While the focus of the election has been on the future of the Rajapaksa regime, other core issues such as the long-term economic challenges facing the country have been largely neglected.

There are high hopes that his departure will kick-start a revival of Sri Lanka’s long-standing democratic traditions, but the chances of renewed political instability and uncertainty remain high.