Students at the University of York are challenging what they see as the closed worlds of nanotechnology and healthcare by crowdsourcing funds to produce a new type of treatment for cancer using magnetic nanoparticles.

Atif Syed and Zakareya Hussein, students in the department of electronics and nanotechnology engineering, are using US-based funding site Microryza to find $3,000 to develop a pharmaceutical patch that delivers tiny nanoparticles into the body via hair follicles.

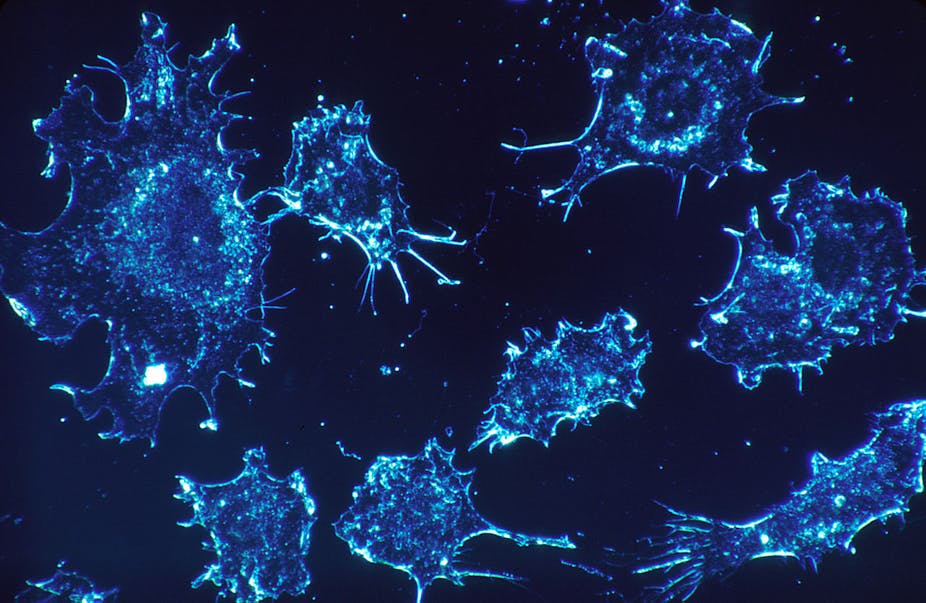

The plan is then to use an external magnetic field such as an MRI scanner to direct the nanoparticles towards cancerous cells. The nanoparticles would be warmed up to a temperature that destroys the cancerous cells before being naturally expelled from the body.

A second use for the proposed nanject patch is as an alternative to traditional injections for delivering medicines into the bloodstream without the use of a needle.

With two weeks to go before the end of their fundraising, Hussein and Syed have so far pulled in 29 donations and have raised more than $1,000 towards their target fund.

The investments have come from some scientists but also the wider public. Among the donors is a lawyer working in New York who is currently undergoing chemotherapy and wanted to support the search for alternatives.

The pair say they are keen to learn from the model of open source software that thrives in the computer industry and apply it to nanotechnology and medicine.

“There is a big need for having openness in the field of nanotechnology so we thought that by going through crowdfunding, we would have a larger audience to reach out to,” Syed explained.

They also believe younger researchers are increasingly seeking to work in this way after decades of dominance by large pharmaceutical companies. Now the patents on many pharmaceutical mega-brands are running out, an opportunity to develop new healthcare products in a different way is emerging.

“A lot of nanotechnology is behind closed doors because people want to patent their products and charge a fortune for them,” Hussein said. “In the same way, medicine is a billion dollar industry. A lot of people who go into medicine are thinking about money to some degree. What we’re thinking about is having enough money to do our research.”

If successfully funded, all the results of the nanject project will be made openly available. This process will start even while the project is still running, with some findings being published along the way. Once the project is complete, the resulting paper will be published with an open licence, so that the findings can be used by anyone but not patented.

Hussein and Syed have even created their own nanoparticles from scratch for the project rather than buying them off the shelf. “Microsoft is commercial but the internet runs on Linux,” Hussein said. “Often if we do things from scratch you can do it better than what is already available. Because we are truly passionate about it we are not going to try to fast track it to success.”

Microryza is one of a growing number of niche websites that aims to help scientists source funding for research projects. The appeal of such sites, compared with more mainstream operations such as Kickstarter, says Hussein, is that they focus on backing potentially high-risk projects.

Dr Marc Ventresca, a lecturer in innovation strategy at the University of Oxford, says more and more students are turning to sites like Microryza. “The crowdfunding sites are a current and important experiment in the broader debate on the fate of very early stage invention funding.” This is particularly important, he says, given the crisis taking place in venture capital for innovation in the US and UK, which is preventing innovative projects from taking off.

Crowdfunding is still in its infancy and some have raised concerns that using this model for science bypasses the safety net of peer review, which helps to ensure the quality of projects funded through more traditional routes.

But Dr David Hone, a lecturer at Queen Mary, University of London, who used Microryza to crowdfund a project on cannibalism in Giant Tyrannosaurs, warns this shouldn’t detract from the potential of such sites to bring in cash for small, short-term projects. “There is of course a risk that poor quality material will be funded or people won’t go through with the work as promised, but then even in mainstream funding some projects go unfinished or lost if people leave them, or circumstances conspire, so it’s not like it’s only an issue for crowdsourcing”.

Each scientist seeking funding has their credentials checked and will generally produce a paper at the end of their project that would be peer reviewed. “In science there is more of a guaranteed product,” he said. “It may be a disaster but you can always get a paper out of it. A negative result is still a result. If you invest in a computer game on the promise that it will be a blockbuster and it fails, then its just a failure. You may as well have just thrown the money in the bin. That’s not going to happen in science.”