Hundreds of thousands of untested rape kits, also known as sexual assault kits (SAKs), languish in evidence storage facilities across the U.S. This backlog denies justice to victims and allows rapists the opportunity to continue to harm others.

Based on research from Case Western Reserve University on Cuyahoga County’s (Ohio) backlogged rape kits, there’s strong evidence to suggest that testing these kits can prevent future rapes. This can happen only when kits are forensically tested for DNA and cases are reopened and prosecuted.

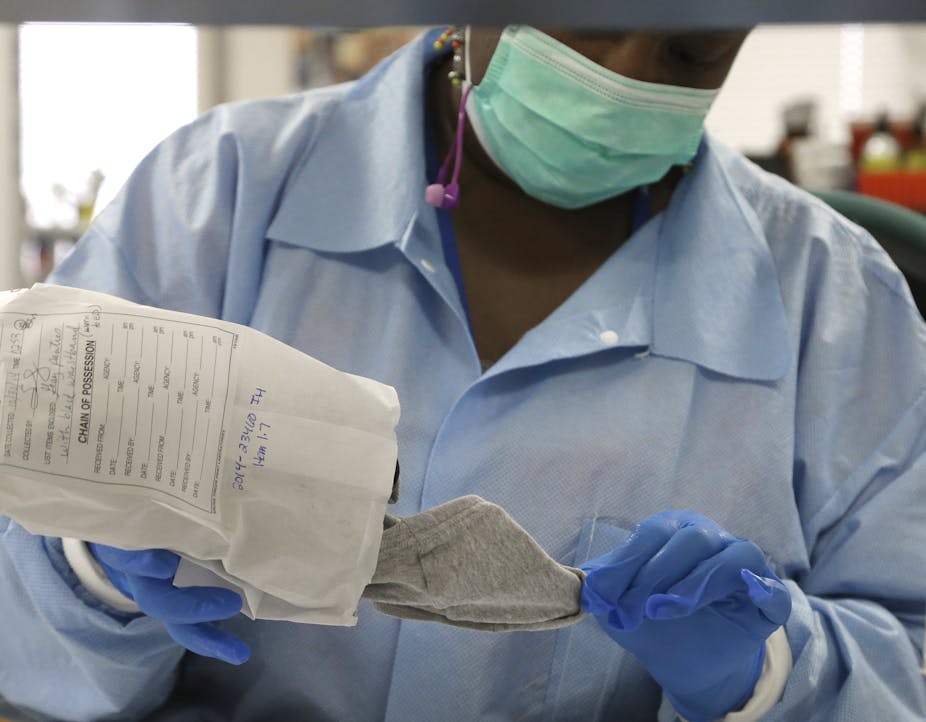

A rape kit is a set of items used by medical professionals for collecting and preserving evidence from victims of sexual assault for investigation and prosecution. Rape kit examinations are usually collected in a hospital, take four to six hours to complete, and involve a medical professional photographing, swabbing and examining the victim’s entire body for evidence.

However, just because evidence was preserved does not necessarily mean that evidence was tested. Until recently, most jurisdictions across the country have not been submitting or testing all rape kits. This has resulted in a backlog of untested kits, estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands.

When kits are not tested, the survivors are often denied justice. After having been traumatized by the rapist, they are also traumatized by a system that forgot about them. As Natasha Alexenko, a survivor whose kit was tested as part of New York City’s backlog and founder of Natasha’s Justice Project, states, “I’m a survivor of a sexual assault and a survivor of the backlog.”

On the other hand, the testing of kits sends a supportive message to the victims that we believe them and that the criminal justice system will overcome the stereotypes and myths that have historically influenced how rape cases are handled. Testing the backlog of rape kits is just the first step in a commitment to reforming and reducing gender bias in the criminal justice system.

Testing does more than soothe the victims and reduce gender bias, however.

Based on our research in Cuyahoga County, we found that untested rape kits also represent a missed opportunity to identify an unknown offender, confirm the identify of a known offender, connect an offender to previously unsolved crimes, even possibly exonerate innocent suspects, as well as populate the federal DNA database.

More than 200 convictions in Cuyahoga County

In the early 2000s, New York City and Los Angeles identified and tested almost 17,000 and 12,669 never tested kits, respectively.

Other jurisdictions followed, including Houston, Texas; Wayne County, Michigan (Detroit); Memphis, Tennessee; and Cuyahoga County, Ohio (Cleveland) by inventorying and submitting their backlogged kits. The results were staggering. There were more than 6,600 in Houston; over 11,000 in Wayne County; over 12,000 in Memphis; and nearly 5,000 in Cuyahoga County.

The research from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) is based on this last jurisdiction, Cuyahoga County. As of the end of September 2016, the Cuyahoga County prosecutor’s office, through its SAK task force, has tested almost all of its 5,000 kits, completed 2,332 follow-up investigations and indicted 527 defendants.

Of the 236 defendants whose cases have reached a final disposition and not been dismissed, 219, or 93 percent, have been convicted. Most of these convictions came from 20-plus years of rape cases, with the testing playing an important role in obtaining convictions in cases where DNA was available. Another 3,498 investigations are currently being conducted.

Key findings on serial rapists

A team of researchers, myself included, from CWRU’s Begun Center for Violence Prevention Research and Education were given access to the SAK Task Force’s case files. We published our findings from the pilot study in a series of research briefs available online which we will summarize here.

These findings have already begun to help reshape what we thought we knew about sexual assault and serial sex offenders. They also help improve the way that sexual assaults are currently investigated and prosecuted.

The most important finding is that the number of identified serial rapists is far more common than previous research suggested. More than a quarter of the Task Force’s indicted defendants are serial rapists – with one of these defendants linked to 17 backlogged kits. In CWRU’s research study, over half of all offenders are serial rapists, although their sample disproportionately comprises serial rapists because the prosecutor’s office gives higher priority to investigating and prosecuting serial sex offenders.

Serial rapists have traditionally been thought of as being a certain type of sexual offender. However, given the number of serial rapists and the ability to observe criminal behavior over 20-plus years, these research findings suggest that it is very likely that a rapist has either previously raped or will rape in the future.

Thus, the takeaway is that we need to investigate each rape as possibly perpetrated by a serial rapist. In doing so, we might reduce future rapes.

Another important finding from this research is the number of serial rapists who raped both strangers and nonstrangers. For the serial rapists with more than one backlogged rape kit in Cuyahoga County in the sample of cases, researchers found that one-third raped both strangers and nonstrangers. This finding supports the task force’s current practice of opening an investigation for all tested rape kits.

As of August 2016, the task force has identified 57 serial rapists who have raped both strangers and nonstrangers. Of these, a sizable number were identified because their DNA from a tested kit in a stranger rape matched the DNA from a tested kit in a nonstranger rape with a named suspect.

For a number of reasons, data from backlogged kits are providing new insights into serial offenders. First, testing allows offenders to be linked to additional crimes via DNA – crimes that might have never been connected.

Second, most of what we know about serial rapists is based on convicted rapists, yet rape convictions are more of the exception than the rule. With unsubmitted kits, crimes are being linked at a much earlier stage in the process – when victims have a rape kit collected. Last, examining a large number of older, unsubmitted kits allows us to examine rapists over decades.

Testing unsubmitted SAKs saves money

CWRU’s research finds that testing rape kits not only makes communities safer but has saved Cuyahoga County a net total of US$38.7 million dollars, or $8,893 per tested kit – so far. This savings does not come from the testing but from following up with investigations and prosecutions – in order words, getting offenders off the street thereby preventing future rapes.

What’s more, the cost of testing rape kits pales in comparison to the costs to victims. A kit costs $950 to test, and a rape costs victims, on average, more than $200,000 in pain and suffering, earnings lost to injury, medical expenditures and decreased quality of life.

In fact, the cost of testing and investigating Cuyahoga County’s kits is approximately $9.6 million while tangible and intangible cost to the victim is $885.5 million.

Thus, even if testing rape kits doesn’t appeal to one’s better nature of providing justice for victims and a safer community, this cost study shows that these efforts can save money and prevent future rapes.

A change in law will help

Moving forward, we must learn from past mistakes. Testing reform has already begun in Ohio. Effective March 2015, Ohio Senate Bill 316 mandates jurisdictions submit all kits for testing.

But testing is only the first step. CWRU’s research findings highlight the importance of investigating and prosecuting for identifying serial rapists and preventing future rapes. However, this requires law enforcement to be properly resourced to fully respond to rapes and trained in victim-centered approaches.

Of course testing and following up on kits is the right thing to do for the victims. The experience of collecting a rape kit is invasive and especially so right after a victim has been traumatically assaulted. These victims did what they have been asked to do to preserve evidence. But that evidence just sat, untested. We hope our findings will show how better processes around testing will better honor victims, result in prosecutions, and prevent future rapes.