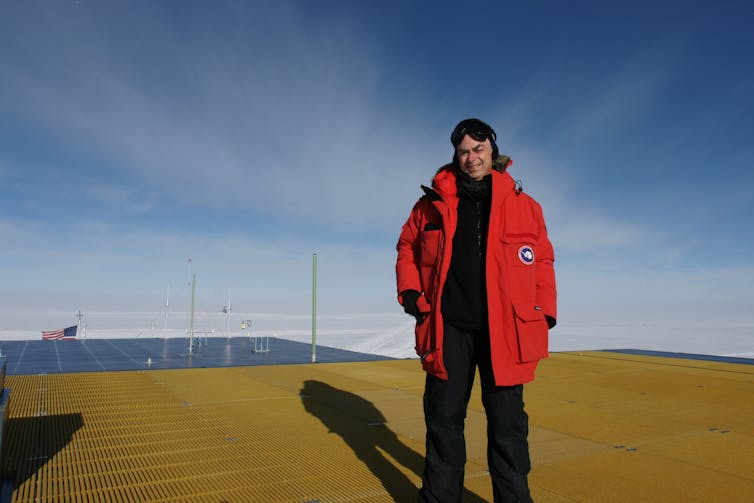

Professor Michael Ashley recently returned from Antarctica where he deployed a telescope to one of the most remote locations on Earth – a place known as Ridge A, 850km from the South Pole.

This is the seventh and final instalment of Professor Ashley’s Antarctica Diaries. To read the previous instalments, follow the links at the bottom of this article.

January 23 – Camp pull-out

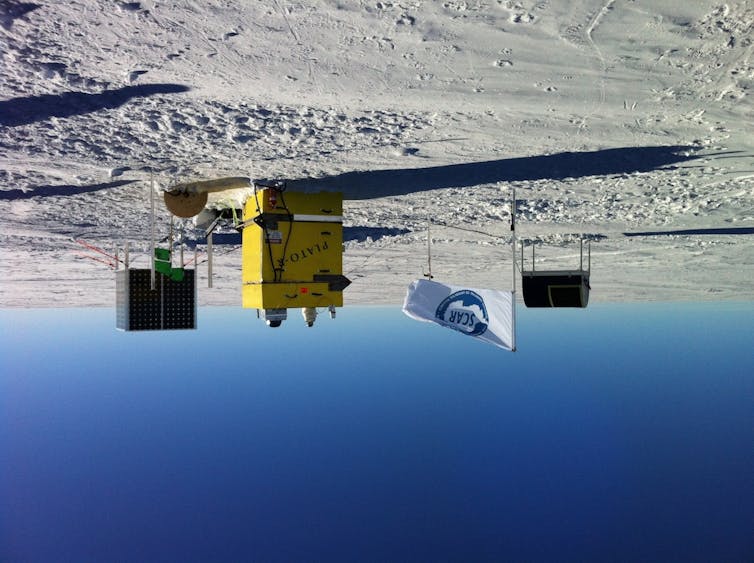

With the deployment of our PLATO-R telescope largely completed at Ridge A overnight, today is the planned pull-out day.

However, the weather puts a spanner in the works, with a prediction of insufficient visibility for a landing at the South Pole for the return flight. The decision is made to hold until the next weather update at 10am.

I inform the guys at Ridge A of the delay via email to the PLATO-R computer (I have stayed at the South Pole). An hour later, in an Iridium call from Campbell [a UNSW colleague], I detect an unmistakable eagerness to return to civilisation. In principle, weather delays could extend for many days, and leave the team living on freeze-dried food and spending most of their days in sleeping bags trying to stay warm.

Fortunately, the 10am forecast looks more favourable, and the Twin Otter crew here at the South Pale race off to ready the airplane for take-off. With almost no load, they will be able to fly non-stop to Ridge A, with an ETA of 2:20pm.

With the knowledge that “rescue” is imminent, the team completes last-minute checks of the experiment and then swings into action to pack up the campsite for a quick and efficient departure.

When Campbell tries to roll up his sleeping mat, it simply snaps into several pieces due to the cold (about -44ºC). Later, when the pilots try to load the bulky and misshapen sleeping mats into the plane, they are dismayed to find that chunks just break off in their hands. This is one useful lesson for future trips to Ridge A: standard sleeping mats, previously found to be adequate at -30ºC, fail catastrophically at -44º.

At 7:15pm I head out to the skiway to await the arrival of the Twin Otter bringing the team home. At 7:20pm the airplane appears as a dot just above the horizon, and at 7:25pm it has landed. I rush over to welcome the adventurers back to civilisation.

Our Canadian Twin Otter pilots have now almost completed their Antarctic season, and will be flying back to northern Canada shortly via Chile and the US.

January 24 – Leaving the South Pole

We all meet at 9am for breakfast to discuss the state of the experiment, and for me to listen to the stories of the deployment at Ridge A. I hear first-hand about the feeling the team had when the Twin Otter took off after dropping them at Ridge A.

It was certainly an unnerving moment to be isolated at almost the highest point on the Antarctic plateau, and having to rely entirely on the resources of the camp. Keeping warm was the main concern, with temperatures as low as -44ºC one has to be very mindful of conserving body heat. And, unlike at the Pole, there wasn’t a warm building the team could retreat to.

The main method everyone used to stay warm was to go on a vigorous hike up and down the skiway.

One obvious effect we hadn’t thought about was that the sun’s elevation changes during the day at Ridge A, resulting in temperature differences of about 10ºC between local “noon” and local “midnight”. The longitude of Ridge A is about the same as India, but our team were on New Zealand time – the time zone used at the Pole.

As a result, they were trying to work outside during the coldest part of the day. With more foresight we should have moved our sleeping schedule to the new time zone.

The extreme cold also had some interesting consequences at meal breaks. The piping-hot, hearty soups that our mountaineer guide Loomy made for dinner would begin to freeze rapidly from the outside in. The centre would remain warm (for at least a few minutes), while ice would start forming on the periphery. The metal spoon would be warm where it touched the soup, but the handle acted as such an efficient heatsink that the team’s fingers were in danger of frostbite.

Fortunately the tents were very effective, and the sleeping bags were toasty warm.

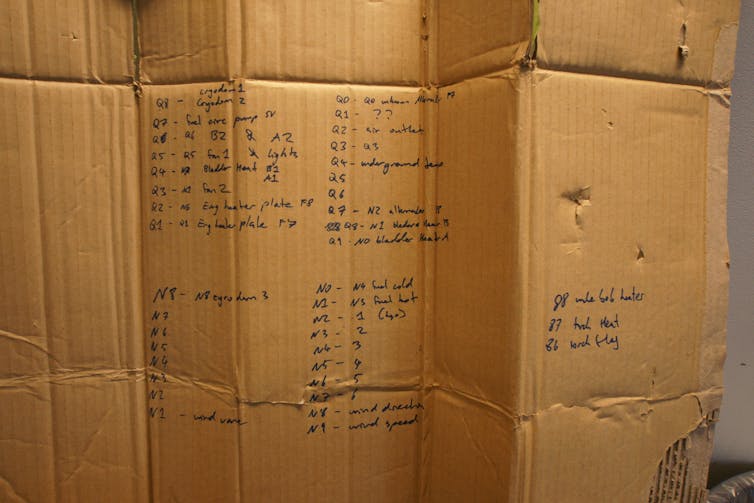

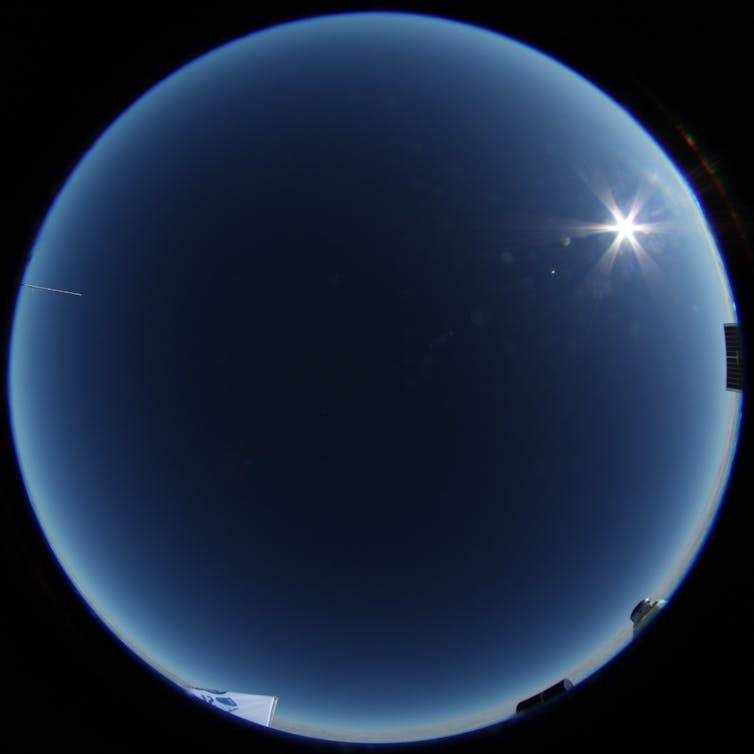

Everyone is very buoyed that PLATO-R is communicating via Iridium and working well. There is a general feeling of disbelief that we have actually pulled this off, and pretty much according to plan. The challenge now is to keep the observatory functioning throughout the winter, and to command the telescope to take data that will lead to a better understanding of star formation. With luck, we will be presenting data from HEAT [High Altitude Antarctic Telescope] at the International Astronomical Union Annual General Meeting in Beijing in August.

But before then there are two crucial time periods we have to be concerned with:

- the next days to weeks where we need to ensure nothing unexpected happens to PLATO-R that could cause us to lose control of it

- the period in a couple of months when the sun sets and we transition from solar power to diesel engines.

If the engines stop and the batteries cool below -25ºC, we won’t be able to restart the engines until October. With winter temperatures hitting -75ºC, we require careful thermal management.

To make it easier for me to control PLATO-R (and PLATO-A - my Chinese colleagues left Dome A this morning, and I’m now responsible for running this observatory too) I was very keen to leave the South Pole and get to somewhere with a decent internet connection.

With this in mind I requested to leave on the afternoon’s flight to McMurdo Station. I left the Pole at 4pm, left McMurdo at 12:30am, and arrived at Christchurch at 9am. Within 25 hours of leaving the South Pole I was back at home in warm, wet Sydney.

Quite a contrast.

Final words

That just about wraps up my Antarctic adventure for 2011-12. It all worked out about as well as I could have hoped. I am still somewhat stunned that in three days we managed to install a completely remote astronomical observatory at Ridge A, and we will now be observing stars being formed in the Galactic Plane for the rest of the year.

In a month or so you should be able to google “PLATO-R” and see our new website with the latest data and photos from the new observatory.

I hope these diaries have given you some insight into what it is like to be a scientist working in Antarctica. It is certainly a privileged position to be in, and I am very grateful for the opportunity.

For those that are interested, I will be giving a talk on the PLATO-R/HEAT deployment during UNSW’s Orientation Week. It is currently scheduled for 2pm on Thursday, February 23, in QUAD Room 1001 off the Basser Steps.

This is the final instalment in Michael Ashley’s Antarctica Diaries. Follow the links below to read the previous instalments: