You’re probably familiar with the TV or movie plot device where a character is conked on the head, loses memory or identity and then gets conked again and memory is restored. Classic examples are in the 1951 Tom and Jerry Cartoon Nit-Witty Kitty and the movie “Clean Slate.”

This “double-conk” myth is so far off from neurological fact that it is laughable to scientists and physicians. It’s never a good idea to hit someone on the head as a cure for any type of concussion or brain injury. Yet surveys of the public find that around 40 percent believe that a second blow to the head can help someone recover forgotten memories.

I’m a clinical neuropsychologist and I study memory and memory disorders. In the classroom, I use movies to demonstrate how brain science and neuro-myths are depicted in popular film. Amnesia is a popular theme. In fact, there have been more amnesia movies made than for any other type of neurological disorder and many of them depict the myth of the “double-conk.”

So I wanted to find where this idea first came from. Did it just emerge from the mind of a creative Hollywood writer or filmmaker? I was surprised to find the origins of this particular myth go back to the early 19th century.

Back to the early 19th century

I went through troves of old movies and books, tracing the myth back to the silent movies of the early 20th century and late 19th-century fiction, including novels published in serialized form in newspapers.

In my research I also uncovered what I would call “pop psychology” newspaper stories about memory, many of which are wildly inaccurate, but reflected what was being written for the public. Then I tried to align the emergence of the double-conk story theme with both scientific and popular writings about brain and memory functioning from the 19th century.

To my surprise, I found what I believe may be the first “scientific” endorsement of a “double-conk” cure in the writings of French physician Francois Xavier Bichat, published after his death in 1802.

Bichat was a young up-and-coming anatomist who believed that the two brain hemispheres were identical in structure and function. In a healthy brain, he reasoned, the hemispheres are in balance with each other and therefore in symmetry. Therefore, if a person is hit on one side of the head, the brain can lose balance, causing confusion or mental derangement.

The cure, in Bichat’s opinion, was a blow to other side. He wrote that “observations so frequently repeated of an accidental blow upon one side of the head having restored the intellectual functions, which had long remained dormant in consequence of a blow received upon the other side.”

My suspicion is that Bichat’s endorsement of a double-conk cure is based on folklore idea because he doesn’t cite or explain any individual cases to support his claim, while implying that a second blow restoring function is a common occurrence. He then uses this example, without question, to support his ideas of brain symmetry and balance.

Bichat’s idea fit prevailing views of brain injury

To a modern scientist, it’s easy to wonder why anyone would think a double-conk cure is reasonable. We now know that hitting the brain, or even shaking it, can cause temporary or permanent structural damage to neurons.

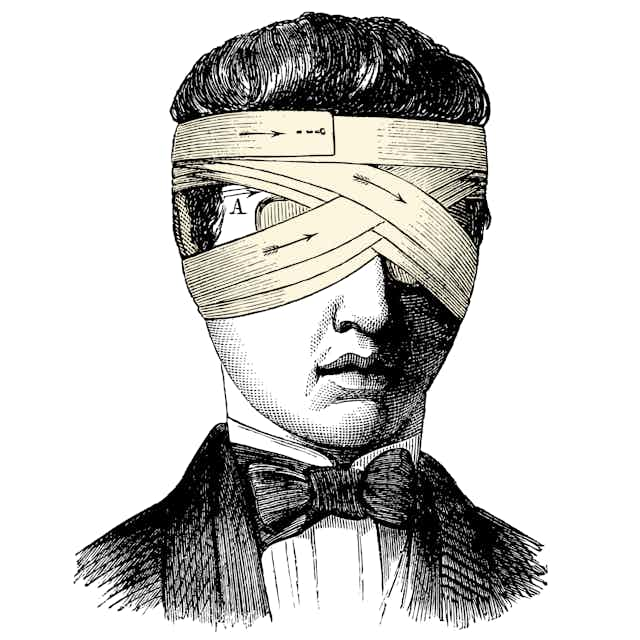

But, in the early 19th century the thinking was that concussion, or any brain injury, did not cause permanent structural or neuronal damage but a general “commotion” or “derangement” of the brain. It was generally thought that concussions, or any imbalance in the brain, could cause problems in thinking and memory, and could also lead to insanity. So Bichat’s proposal of brain symmetry and a second blow helping to “rearrange” the problems caused by a first blow fit into the prevailing view about concussions.

Later on Victorians also thought that any type of “nervous shock” caused a physical effect on the nervous system. Electricity could provide a nervous shock, as could terror, grief or a blow to the head. All physical or emotional shock was considered to have the same effect on the brain and nervous system.

Many problems were thought to be the result of an unbalanced brain. Indeed, several early and mid-19th-century practitioners believed shocks, whether physical or emotional, could be useful to bring someone out of coma, or a stupor. Hysteria, a catch-all diagnosis often given to women for a wide variety of “nervous” symptoms, was sometimes treated by slapping the patient.

Considering that many Victorians saw the brain as a machine it may have appeared reasonable to them to “knock some sense” back into someone. A shock to the system would get the cogs moving again and bring the brain back in balance, like someone hitting a machine on the side to get it working again.

What about amnesia?

So how did all of this become connected to amnesia? While Bichat wrote only generally about “intellectual” problems, it had been known since ancient times that traumatic brain injury could cause memory problems. However, there was another prevailing myth circulating at the time that memories could never be lost. This was also was reinforced by “pop psychology” writers of the 19th century.

Many of us have had the experience of a “memory jog,” or a cue that brings up a long forgotten memory. Perhaps because our own experiences serve as powerful evidence to us, this also reinforces the myth that all memories are forever stored in the brain and only need some sort of jolt to come back.

It’s hard to know exactly how the double-conk myth became intertwined with the myth of memory restoration, but forgetting and amnesia were also popular themes in Victorian novels. If memory could be restored with a shock, a second conk could provide that jolt.

It wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century that a few scientists studying memory began to fully realize that a blow to the head might destroy some memory abilities completely. A second blow wasn’t likely to jump start the brain, they realized, but create further damage.

But the double-conk myth was already in circulation by then. The fact that the myth was originally supported by some scientists and physicians probably lent it some credence even as evidence that it wasn’t true mounted. It’s hard to change a myth with a 50-year head start.