Writing on the domestic history of the United States in the twentieth century has been dominated by work on the great reform movements of the era - Populism, Progressivism, and the New Deal.

What is striking is that what was arguably the most significant reform movement of them all – Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society – has received relatively scant attention.

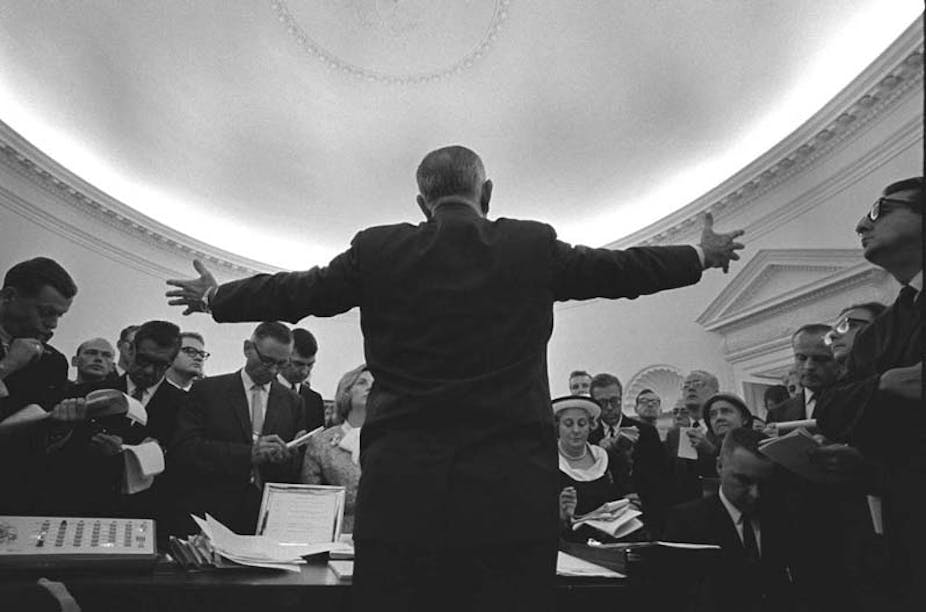

That is unfortunate in no small part because passage of Lyndon Johnson’s domestic program is a lesson in “when politics worked.”

Significant impact

Some of the Great Society programs were more successful than others, but no reasonable observer can question their impact.

Between 1963 and 1970, when Lyndon Johnson left office, the portion of Americans living below the poverty line dropped from 22.2 percent to 12.6 percent. Medicare since 1969 has provided health care to 79 million Americans who would otherwise not have received it and in the process desegregated Southern health facilities. (There are questions about its financial sustainability, however).

And what would have become of the nation, particularly the American south, without the civil rights acts of the 1960s? Failure to provide African-Americans with full citizenship and some degree of opportunity would have led to a national crisis that would have made Vietnam and Watergate pale by comparison.

What is exceptional about the thousand pieces of legislation that Congress passed during the Johnson presidency was that they were not enacted during a period of great moral outrage by the middle class at malefactors of great wealth, a period that spawned populism. They did not come about because of fears that the country was about to be overwhelmed by alien immigrant cultures, fears which helped spawn a progressive movement. Nor were they passed in the midst of a crushing depression that threatened the very foundations of capitalism, a crisis from which emerged FDR’s New Deal policies.

The Great Society has its own history

The two obvious power sources for the reforms of the 1960s were the civil rights movement and the cold war.

The violence directed against blacks, especially children, during the 1963 protest marches in Birmingham seemed to dramatically, if temporarily, alter racial perceptions and to mobilize the consciousnesses of white middle class Americans.

In the wake of the launching of Sputnik in 1957, the nation underwent a long season of soul searching. If the United States was not to be gobbled up by the communist superpowers, JFK and others argued, it must prove the superiority of liberal capitalism over Marxism-Leninism.

But there were other factors as well.

The youth rebellion of the 1960s which spawned the free speech movement and the Students for a Democratic Society offered up a new, searing critique of American society. Joining with left-leaning faculty and public intellectuals, Tom Hayden and his cohort denounced Jim Crow, the military-industrial complex, and the complacency of New Deal liberalism.

Finally there was Lyndon Johnson himself.

LBJ’s grandfather had been a populist, and he and his family lived through progressivism and The New Deal, fully embracing their objectives.

Having represented conservative and business interests while a US senator from Texas, Johnson threw caution to the winds when he became president and promised to create that more perfect union that reformers past and present had been calling for.

Time for a reevaluation

The reasons why the Great Society has been ignored by historians and deplored by public intellectuals are fairly obvious.

Vietnam has been an albatross which the historical LBJ has been unable to shed. Most academics of my generation were fervently committed to the anti-war movement and have never been willing to forgive the Texan for thrusting the republic more deeply into the Vietnam quagmire.

For FDR, US participation in World War II enhanced his moral credibility and in the process the reputation of the New Deal. For LBJ escalation of the conflict in Vietnam bankrupted him morally casting a dark shadow over the Great Society.

During the 1980s, LBJ and the Great Society became the perfect whipping boy for Ronald Reagan and the New Right and there was no one to defend them.

Then, there is the enduring cultural and political power of Camelot.

The Kennedys detested LBJ as a usurper, a man who through no merit of his own became president and reaped the harvest that [JFK had sowed.](http://www.amazon.com/LBJ-Architect-American-Randall-Woods/dp/0674026993

At a speech delivered to the 18th annual convention of the Americans for Democratic Action in the spring of 1965, Arthur Schlesinger attributed the concept of the Great Society entirely to (Kennedy appointee and then Johnson speechwriter) “New Frontiersman” Richard Goodwin.

The implication, then, is that all of LBJ’s men - Jack Valenti, Horace Busby, and George Reedy - were against the idea. Schlesinger went on to hail the triumph of Goodwin’s proposals as “a clear victory of the liberal cause of American politics over the messianic conservative complex of the Texas mafia.”

Nothing could have been further from the truth.

Johnson’s advisers, like Johnson himself, were dedicated reformers committed to the notion that the primary purpose of government is to secure social and economic justice for all.

It is, finally, the case that LBJ and Martin Luther King were uneasy allies. Some civil rights veterans see accolades heaped on Johnson as somehow diminishing King. The makers of the newly released motion picture Selma demonize Johnson, attributing, for example, the FBI wiretapping of King to LBJ rather than to Jack and Bobby Kennedy who actually authorized it.

But perhaps things are changing. My generation is passing from the scene and a group of young talented historians in this country and the United Kingdom are stepping forward to give the Great Society the attention it deserves.

Foreign scholars, critical of Vietnam though they might be, do not have the psychological and emotional investment in the antiwar movement that US academics have had.

Perhaps in the process, they will restore some balance to the nation’s political dialog.

At a Great Society conference at Hunter College in 2011, no less a critic of the Vietnam War than George McGovern pronounced LBJ to be, next to FDR, the greatest president of the twentieth century.