By the 1870s, photography was a ubiquitous presence in the colonial life of Aotearoa New Zealand. For Māori, however, it was also a colonising tool – part of the colonial practices of land alienation, war and propaganda that affected them so deeply.

This complex Māori engagement with photography features in A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa, an exhibition that opens today in Auckland.

A collaboration between Tāmaki Paenga Hira–Auckland War Memorial Museum, the Alexander Turnbull Library and Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena, the exhibition and associated book from Auckland University Press showcase the photographic riches of three nationally significant collecting institutions.

Starting with the arrival of photography in Aotearoa in the 1840s, the book and exhibition chart technological developments and cover a wide range of photographic genres, from studio portrait to amateur photography.

These photographic beginnings were deeply embedded in the making of the settler state. Its invention coincided precisely with the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, which ushered in formal British colonisation.

And it was also in the region where Te Tiriti was signed that Captain Lucas of the French barque Justine is believed to have experimented with making daguerreotypes in 1840-41.

Because of these links, photography’s technological development and its different uses can’t be understood without reference to the political, cultural and economic contexts of colonisation.

The settler lens

Photographs are complicit in colonialism because they were used to document the impacts of migration, settlement and land transformation. For example, they illustrate the advance of settlement and the subjugation of Māori after the Waikato War (1863-64).

Imperial officers such as William Temple, who was active in military campaigns to advance European settlement, photographed two icons of colonisation: roads and military camps.

An Irish-born soldier, Temple followed the Great South Road on foot and with his camera as the route advanced towards the border of Kiingitanga territory. One of his photographs (above) demonstrates the impacts of the Great South Road on the local environment.

Read more: Frozen in time: old paintings and new photographs reveal some NZ glaciers may soon be extinct

Photography’s commercial interests also aligned with colonial propaganda, especially as landscape photography grew in popularity from the 1870s. Historian Jarrod Hore has demonstrated how landscape photographers helped shape settler attitudes to the environment, but also documented colonial progress.

Photographs were used to illustrate engineering successes and the advancing tide of settlement. For instance, John McGregor’s 1875 photograph (below) depicts the clearing of Bell Hill in Dunedin. In the background, the church embodies the possibilities of colonial advancement enabled by environmental transformation.

Our early photographers were, in Hore’s words, engaged in “settler colonial work” because they “mobilised and visually reorganised local environments in the service of broader settler colonial imperatives”.

The photograph as taonga

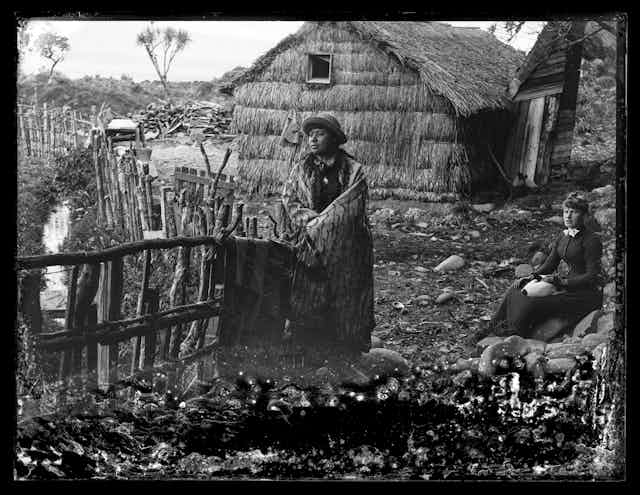

Indigenous peoples were a particular focus of early photography in other settler colonial societies. New Zealand followed this pattern and Māori feature prominently in our colonial photographic record.

As soon as photography arrived in the colony, Māori were captured by the camera. Itinerant daguerreotype photographers travelled the new colony in the 1840s and 1850s to exploit the commercial opportunities available in new colonies such as New Zealand.

Reproduction of colonial tropes became common in commercial photography, reflecting the collectability of Māori as photographic subjects. The carte-de-visite, popular from the 1860s and of a size that could easily be posted, meant images of Māori found their way into albums all around the world.

Such images became an important part of the business for studio photographers in the colonial period.

At different times, and depending on the context, Māori embraced or rejected photography. Because of its colonial implications, Māori whānau and communities have a complicated relationship with the camera. But, as scholars Ngarino Ellis and Natalie Robertson argue, there is evidence it was regarded as friend as much as foe.

Māori have long integrated visual likenesses into customary practices, such as tangihanga (funerals), while portraits adorn the walls of wharenui across the country.

Colonial photographs are culturally dynamic. Their integration into Māori life means they do not just depict relationships but are imbued with them. As such, photographs are taonga (treasures) and connect people across time and space.

Te Whiti and the camera

Māori also took up the camera. Canon Hākaraia Pāhewa, for instance, was a skilled photographer who took his camera on his pastoral rounds, during which he recorded scenes of daily life.

He depicted people at work and documented transformations of landscapes, important cultural events, religious service and domestic routines. These photographs bring to light the diversity and richness of Māori life in the early 20th century.

Māori whānau already valued and used photographs in a variety of ways in the 19th century. Photographs were memory containers, mementos of family, markers of personal transformation, and generators of social connection.

Read more: Yevonde: an introduction to the woman who pioneered colour photography

Designed to be shared and displayed, photographs were prompts for discussion and storytelling. They are visual records of whakapapa, identity and notions of belonging. They also mark Indigenous presence and survival in the face of settler colonialism.

At the same time, though, photography’s role in advancing colonialism meant Māori were cautious about the reproduction of images. There was an awareness of what could happen to photographs once they were out of the subject’s control.

In 1907, Te Whiti, the Māori prophet and leader of the pacifist settlement at Parihaka, died. Established in 1869, Parihaka attracted thousands of Māori during the 1870s. Many of them were dispossessed by the wars of the 1860s and 1870s. In 1881, over 1,500 armed constabulary invaded the community, whose residents met them with passive resistance.

Te Whiti had always refused to have his photograph taken, as did his co-leader Tohu Kākahi. Ironically, their settlement was richly documented by photographers when the two men were alive, and has inspired many artists ever since.

Read more: How NZ's colonial government misused laws to crush non-violent dissent at Parihaka

The writer William Baucke claimed Te Whiti “detested with horror photographs and prints in which the protruding tongue and inverted eyeball are depicted as symbolic of the Maori”.

Baucke certainly embellished this description, but Te Whiti did fear that a photographic likeness, if taken, would undermine his ability to control his self-image. He didn’t always succeed in controlling the camera, as James McDonald’s painting (below), based on a photograph, shows.

Visual sovereignty

In refusing to be photographed, Te Whiti was engaging in what Tuscarora scholar, artist and curator Joelene Rickard characterises as Indigenous visual sovereignty.

Rickard has used this concept to describe how Indigenous photographers today are making “assertions of spiritual and political sovereignty”. But she is also highlighting long traditions of Indigenous art-making as sources of empowerment and assertions of sovereignty.

Te Whiti’s refusal to be captured by the camera was an act of visual sovereignty because he recognised the qualities that made a photograph so exciting also made it dangerous: it was portable, collectable, and it was a business.

Read more: Portrait of Hemi Pōmare as a young man: how we uncovered the oldest surviving photograph of a Māori

Right now in Aotearoa New Zealand, when the political climate is hostile to Te Tiriti, te reo Māori and tino rangatiratanga, it is important to be reminded that Māori resistance and resurgence have long histories.

They appear in our photographic record in numerous forms – in Hākaraia Pāhewa’s record of the vitality, dynamism and energy of Māori life in the early 20th century, and in Te Whiti’s refusal to engage with photography, which undermined its power as a settler colonial technique.

Te Whiti’s rejection of the camera is suggestive for historians of photography, too. Rather than seeing Māori refusal to engage with photography as embodying a fear of a new technology, perhaps it was a denial of the settler colonialism the camera embodied – a claim to visual sovereignty and the ability to control one’s self-image.

A Different Light – First Photographs of Aotearoa: Auckland War Memorial Museum, April–September; Adam Art Gallery, Wellington, December 2024–June 2025; Hocken Collections, Dunedin, August 2025–January 2026.