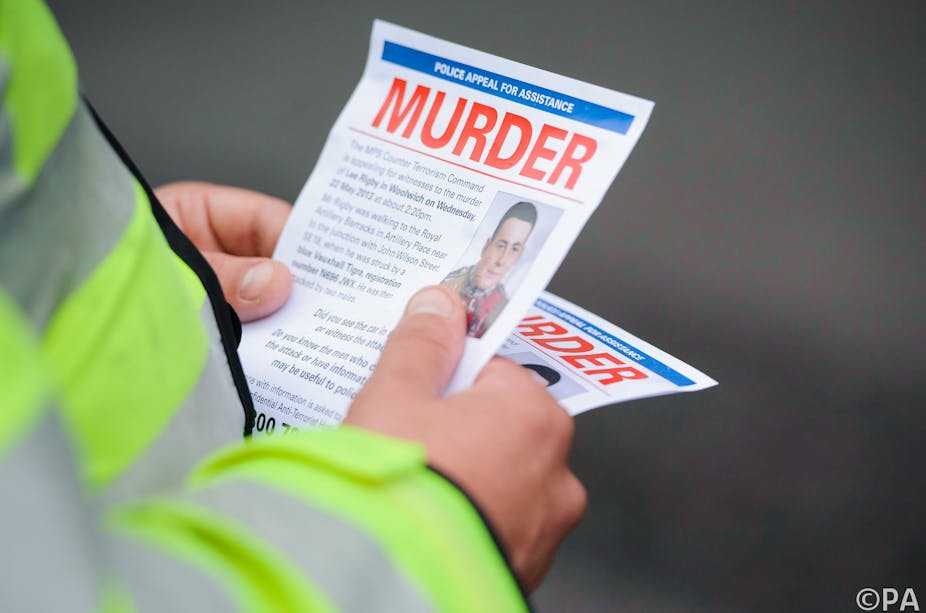

There are strong parallels to be drawn between last week’s Woolwich murder and the Boston bombings in April, and not just because of the terrorism connection. The subsequent shooting and hospitalisation of the suspects in both cases raises the issue of how police and law enforcement agencies interview (or interrogate) suspects who are injured.

One of the suspects in the Woolwich murder, Michael Adebowale, has now appeared in court while another, Michael Adebolajo, remains in hospital. In the US, only one of the bombers survived. In these, as is the case in other horrific incidents, interviews with the attackers will be used to establish the facts and why they committed such crimes.

Obtaining complete, accurate and reliable information is central to any criminal investigation and how this is done is especially important in high-stake crimes such as murder and sexual offences, and acts of terrorism as happened in Boston and Woolwich, where suspects may have a great deal to lose if they admit they were involved.

It’s vital for victims, their families, the public, and the suspects - for whom there will be little sympathy - that they are given a fair hearing regardless of the public outcry. And police must try and remain impartial at all costs in the interests of justice.

However, such cases can be very demanding for the police interviewer especially when public emotion is running high. So what techniques are used by the police in the UK and US to obtain accurate information and can we in the UK learn anything from other countries?

US and UK methods of interrogation

There are vastly different methods used to elicit information. In the US (and some other countries) one such technique is the Reid model of interrogation.

A non-accusatory and non-coercive “behavioural analysis interview” first tests whether or not a suspect may be guilty of an offence using a range of measures. However, this has been repeatedly found by researchers to be unreliable as many signs of guilt have also been shown in people who have turned out to be innocent.

A nine-step process then follows. This includes manipulation of the suspect (via persuasion); minimisation (of the seriousness of the offence) and maximisation (both of the severity of not confessing, and the benefits of confession). Interrogators are also encouraged to tell suspects that any denials would be futile as they are sure of the suspect’s guilt.

Interrogators are also able to lie to suspects about the nature and strength of the evidence against them - something that isn’t allowed in the UK.

Supporters of the Reid technique claim that the nine-step interrogation process is an effective method for obtaining confessions from guilty suspects. But not surprisingly, psychologists were (and still are) concerned with this approach, and argue that such oppressive interviewing methods are, in fact, likely to lead vulnerable individuals to falsely confess to crimes that they didn’t commit.

One of the most common and “humane” methods of eliciting reliable and accurate information is by way of an investigative interview that doesn’t seek a confession. In this kind of interview suspects are provided with an opportunity to explain the nature of their involvement in an event, without the use of oppressive techniques.

In England and Wales, this is carried out using a model of interviewing known as the PEACE model: Preparation and planning, Engage and explain, Account, Clarify and challenge, and Evaluation of the interview.

This model provides a planned, ethical and fair means of interviewing, and encourages interviewers to remain open-minded at all times while actively engaging with interviewees to obtain accurate and reliable information. But how do interviewers remain “engaged” with suspects of high-stake or disturbing crimes?

A large body of research has looked at the effectiveness (or otherwise) of different questioning techniques. There is now overwhelming evidence that suggests using open-ended questions, for example those starting with “tell me”, “explain why” and “describe”, as well as probing forms of questions - what, when, where, why, who and how - are the most productive and encourage interviewees to engage and freely recall events. This in turn is also associated with fuller and more accurate accounts.

These types of questions are classified as “appropriate”. Conversely, “inappropriate” questions, including those that are closed-ended, encourage interviewees to answer using recognition memory - retrieving knowledge of previous experiences and events - rather than using free recall. This can dramatically increase the probability of error in the answers provided.

Control, speed and power

International research has found that police officers tend to use more inappropriate questions than appropriate ones when interviewing high-stake offenders. Researchers are still searching for an answer to this, but there are three factors that could help explain this: control, speed and power.

Control; whoever is asking the questions must remain in control of the interview. When faced with something that is viewed as repulsive or something that is not understood, many will attempt to control the situation. Asking mostly closed types of questions puts the interviewer in control and gives the interviewee very little room to explain him or herself. In the case of high-stake crimes, officers may find the details distasteful so they might try to limit their emotional exposure to them.

Speed; an interview that mainly seeks confirmation of known facts by way of closed questions is faster to conduct than other forms of investigative interview. Conducting a speedy interview reduces physical (and psychological) exposure to a suspected offender whom an interviewing officer may dislike.

Power; rather than showing empathy, some interviewers may seek some kind of persecution of the offender, for example if they’re a paedophile. If the questions asked are closed in nature, there is no opportunity for the interviewee to try and rationalise their behaviour, plead their case or relive events in a way that excites them. Although subtle, it takes away the suspected offender’s perceived power from the officer.

Many other researchers argue that to keep a suspect engaged during interview, they should use an empathic approach, which they say is paramount to gain a confession. In a police context, empathy is about having the ability to understand the perspective of the interviewee, to also appreciate the emotions and distress of that person, and to communicate that directly, or indirectly, to the interviewee.

There have been very few academic studies on the use of empathy in police interviews, but recent research in the UK suggested that the use of empathy (by itself) had no impact on the amount of relevant information obtained in interviews with suspected offenders of child murder, child sex offences and adult murder.

There is little sympathy for terrorist suspects and public opinion after such events strongly hint to the use of more oppressive techniques of interview. It may be one of the most demanding tasks to ask of a police officer but interviewing the Boston and Woolwich suspects in the right way will ultimately give us the best information and justice.