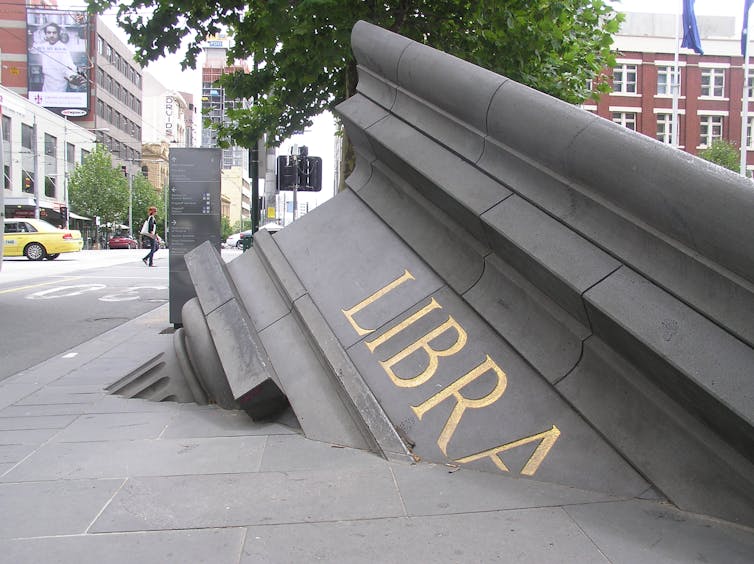

The State Library of Victoria, founded in 1854, is one of the most visited libraries in the world. And right now it is in the middle of a crisis.

Leading Australian authors such as Grace Yee, Michelle de Kretser and Tony Birch have resolved to no longer work with the library – unless its leaders demonstrably change course. Library staff, too, have been strongly critical of management; its head of audience engagement has resigned.

Public disputes between staff and managers have happened before, but the current controversy is unusual in its scale and intensity. Unusual, too, is the boycott by respected authors, who have hitherto been among the library’s most natural allies and partners.

The dispute began with the decision to cancel or postpone (both verbs are contested) a program of “Teen Bootcamp” workshops – funded by the Serp Hills Foundation and the JTM Foundation – for young writers. The library had engaged six authors, including Jinghua Qian, Omar Sakr, Alison Evans and Ariel Slamet Ries, to conduct the workshops.

On social media and elsewhere, the writers had voiced their support for the Palestinian people in the face of Israel’s full-scale invasion of Gaza.

The writers have since written an open letter asking the library to better explain its decision. Hundreds of people have signed the open letter, and more than 100 staff have written to Paul Duldig, the library’s CEO, condemning the cancellation or deferral of the workshops.

Jinghua Qian labelled the conduct of library management “breathtaking” and “disgusting”. Journalist Tony Walker placed the dispute in a wider pattern of intimidation, preventing “free and respectful speech” inside public institutions.

In response to the criticism, library management defended the workshop decision as “apolitical”. Meanjin editor Esther Anatolitis tweeted in reply, “There is no such thing as an apolitical cultural institution”.

A boycott, open letters, petitions, resignations: these are definitive evidence something has gone wrong with the library.

The many meanings of ‘library’

Anatolitis is right. Libraries have always been political. In the UK today, the issue of library funding is central to the reaction against fiscal austerity. In the US, libraries are at the heart of culture wars about LGBTQI rights and social inclusion.

The State Library of Victoria itself has recently spoken out in favour of human rights and against “challenges to intellectual freedom faced by public libraries across Australia, in the form of demands for book challenges, book theft, intimidating protests and threats against public programs including rainbow and drag queen story times”.

The present dispute highlights the many meanings of “library” – and the tensions between those meanings. Is a library a collection of texts? A building for books? A bundle of services? An abstract legal entity? The dispute has also highlighted questions such as who owns the library, and whom the library is for.

Public libraries are porous. Major libraries today run a variety of complementary programs in areas such as education, conservation and outreach. They are accessible in a physical sense, and they should also be open and accessible in their governance and leadership.

The State Library of Victoria has handled the dispute in a manner that brings to mind fiascos in the corporate world. Non-transparent decision-making, muddled communications, the apparently clumsy attempt at “risk management” that created the problem in the first place: the imbroglio has a distinctly managerialist feel.

A paradox of neoliberalism over the past three or four decades is that, when commercial-style governance is applied in traditionally less commercial spheres – such as libraries, universities, publishing and the public sector – it is often applied more rigidly and narrowly than in genuinely corporate sectors, such as banking and professional services.

But libraries are not just another type of corporation, and a library CEO is not the same as the head of a commercial corporation.

For one thing, the ownership of libraries is much broader, encompassing various formal and informal ownership stakes. Libraries are not separate from their communities, and they deliver a range of non-commercial benefits that are hard to assess through a narrow corporate lens.

Read more: Friday essay: the library – humanist ideal, social glue and now, tourism hotspot

Innovation in governance

The State Library of Victoria may be in the middle of a crisis but you wouldn’t know it from its website or press room.

The dent in people’s confidence about its leadership should be the main thing the library is talking about right now, both internally and outwardly. It should be engaging with the library’s communities of owners and users and partners, in real time and with courage.

Instead, management seems to be doing its best to wish the present moment away. That is a standard corporate response, but things could be very different.

Across Australia, state library legislation is not up-to-date with the current mix of library functions, or the current library context. More fundamentally, the standard board-CEO governance model is increasingly ill-fitting.

This is not just about the need for more diverse representation on boards and in management. It’s also about the wholesale adoption of new engagement methods, new modes of planning, and new ways of making and communicating decisions. As public institutions, libraries have a responsibility to be transparent about their decision-making.

In recent years, major libraries’ engagement with user committees and representative forums has sometimes felt half-hearted. But the benefits from genuine engagement and, potentially, collective decision-making could be significant.

Around the world, recent waves of library innovation have focused on the built environment and the breadth of library services. Now, it seems, we need a new wave of innovation in library governance.