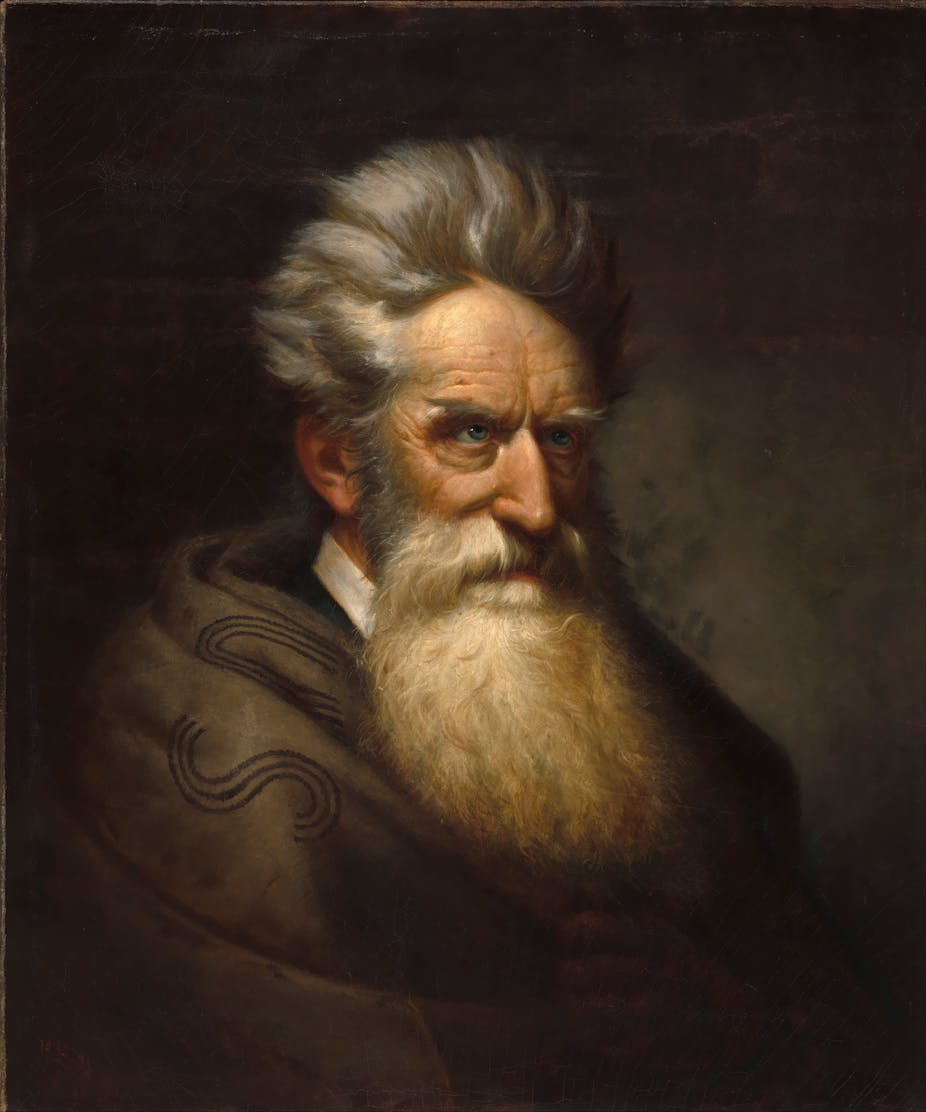

Flailing devil-horn brows; cross-eyed glare; hooked nose; unkempt beard; angular cheek bones; reckless hair, and hands bound in the dark corners of canvas. That’s John Brown, as depicted by Ole Peter Hansen Balling in earthy oil-paint tones, circa 1872.

It was my fourth visit to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC. Airy, flush green olive trees, showery water fountains, golden shards of light; it beat the stuffy DC summer streets and the even stuffier Library of Congress newspaper reading room. But on this occasion, I paid particular attention to the opening line of the box of text beneath Balling’s portrait:

There were those who noted a touch of insanity in abolitionist John Brown …

It reminded me of a display I had seen at the Gettysburg Battlefield Museum just a few weeks earlier. A bold, capital-lettered, mega-font question was emblazoned on the wall, next to a rusty pike and a picture of Brown:

JOHN BROWN. MARTYR OR MADMAN?

And here I was, back at the gallery, staring at the same man, asking myself that same question, like thousands before me.

Born in Torrington, Connecticut in 1800, Brown remains, over a century and a half after his death, one of the most fiercely debated and contested figures in 19th-century American history.

On the evening of October 16, 1859, just months before the American Civil War fully ignited, Brown led a band of raiders into the small town of Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, in a bid to instigate a slave rebellion. Brown’s plan was to seize federal ammunition supplies and arm slaves with rifles, pikes and weaponry in order to strike fear into slave-holding Virginians, and catalyse further revolts in the south.

Greatly outnumbered by local militia and government marines, he was swiftly captured and sentenced to hang, which he did on December 2, 1859.

A symbolic man

While some abolitionists immediately labelled Brown a heroic martyr, others more cautiously warned against his violent approach. Southern newspapers, on the other hand, expressed disgust at how this violent madman could ever be deemed heroic.

Since the 1860s, Brown has been a symbolic cultural resource for interest groups to draw upon, define, explain, or galvanise a course of action or belief. Depending on one’s point of view, he has variously been claimed a heroic martyr for African Americans, one of the greatest Americans of all time, a cold-blooded killer and even America’s first terrorist. But is there a historical “truth” to whether he was actually (partisan bias aside) madman or martyr?

The very idea of martyrdom tends to proliferate during periods of social change and historical action. Martyr stories are also marked by personal quests, violence, institutional execution, and dramatic final actions that heroically demonstrate a commitment to a cause with disregard for one’s own life.

Brown’s violent raid at Harper’s Ferry at the dawn of the Civil War, his theologically-infused commitment to ending slavery, and institutional hanging fit perfectly into these historical patterns of socio-religious martyrdom. So why the “madman” moniker?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the term “madman” as:

A man who is insane; a lunatic. Also more generally (also hyperbolically): a person who behaves like a lunatic, a wildly foolish person.

Problematically, the first part of the definition – “insane” – connotes a mentally ill male, unable to fully control their physical and mental faculties.

But Brown was committed to his final act, and recognised violence, imprisonment and sacrifice as a forum for abolitionism. Consequently, it might be argued that his actions suggest a form of heightened (rather than lack of) self-control, something you’d expect of a martyr.

Cultural stories

However, the second part – to behave like a “lunatic” or “wildly foolish” person – more aptly describes Brown’s personality. There is certainly a case for considering Brown’s final act at Harper’s Ferry to be “wildly foolish”. Even his most famous supporters such as Frederick Douglass described it as cold-blooded, if well intended.

Even if a present-day medical, neurobiological, or psychological analysis of Brown was possible, however, his actions would surely be considered outside the realms of what psychologists call a healthy “clinical population”. That is, his class of behaviours stretched beyond the limits – psychological, mental, physical – of the normative masses. Which begs the bigger question: is it not a streak “madness” that always makes a martyr?

So, the futile question of whether Brown was madman or martyr is irrelevant: Brown was, and will continue to be, both.