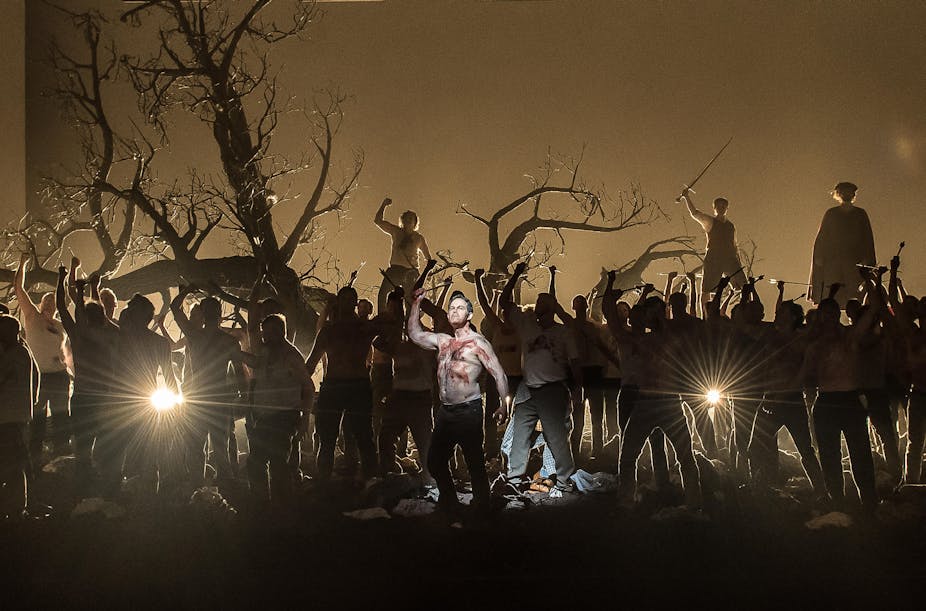

There’s a well-known quip from American comedian Ed Gardner: “Opera is when a guy gets stabbed in the back and, instead of bleeding, he sings”. It seems now, that in the name of renewing opera, he has to sing and bleed. Or rather, she has to be raped while someone else is singing and music plays. This “innovation” is what has outraged London’s famously reticent audiences at the Royal Opera House’s most recent production of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell.

With personal disquiet, I have noted a tendency in contemporary productions to align opera with the Tarantino school of cinema. In the past, Hollywood cinema invented subtle ways to represent sexuality or violence, because films had to get round the puritanical scrutiny of the censoring Hays Code. Necessity freed sexuality from explicit depiction – the realm of pornography – paradoxically eroticising the entire film from colour to costume, from setting to facial expression.

Who can forget the erotic effect of a pillow thrown from couch to double bed which concludes, and heterosexualises, Richard Brooks’ 1958 film Cat on a Hot Tin Roof? But now, in most movies, we are subjected to a kind of infantile literalism that does nothing for the erotic. It merely normalises watching the mechanics of other people having sex, and the sight of violence inflicted on those made dispensable by the logic of the film.

The hunger for violence

This literalist turn displaces imagination and is misunderstood as freedom of expression and the expansion of the medium into greater truth. It tries to persuade us that it is radical to introduce “realism” into opera. This has several negative effects. Firstly, the audience – whether willing or unwilling – becomes witnesses to a performed violence sometimes verging on the obscene and made as credible as it can be. Violence moves from the realm of the implied, codified, and represented, into the sphere of imitation, as if the audience has no capacity to imagine implied horrors and remember passion. Live art, moreover, does not have the get-out clause used to defend (wrongly in my view) violence on the screen, where it is not real, but manufactured by special effects.

Secondly, live art requires actors to perform the simulated violence as authentically as possible. Acting demands conviction, gestures of the actual bodies before our eyes made credible by their use of memories or images of sex or violence. In the case of a woman stripped and apparently raped that outraged its audiences at the Royal Opera House, the actress has to affect the actual experience of violation, as a condition of being in the staging, as conceived by director Damiano Michieletto.

In the hunger for new explicitness, defended as new and radical, it is worth considering the ethical effects of the traumatising demands made by the directors on vulnerable women in performance. As tools of the director’s imagination, actors are dragooned into actions and exposures that feed a violent imagination on both sides of the stage. What does it do to them? And what does witnessing it do to us?

The defence against the criticism of the enactment of violent rape in the Royal Opera House production of Guillaume Tell cites the implication of a rape in the libretto, as a textual suggestion. Yet the audience is given no choice but to “see” the rape realistically performed by men on a woman. It becomes a done thing: it is enacted before our eyes. If we were to extend this logic, operas which suggest that men go off hunting would require us to see the actual killing of the animals, to convey the “realness” of aristocratic power over life and death “implied” by the text. This would cause such outrage that it is difficult to imagine what defence could be mounted.

Literalising a textual imputation is not, in my view, a road to the “renovation” of opera. Instead, it renders the art form banal and degrades both audience and performers. We do not need sexual explicitness nor realistic violence in opera because it is already an art form that codes violence or eroticism, political brutality or thwarted passion. These features are “performed” musically, created by the unique of the capacities of the human voice to blend with instruments and produce an impassioned effect. Opera is not stories set to music. It is the vocal-musical translation of passion or violence into sound. In one sense, it is all there in the music.

Opera is deadly

This is not to vindicate opera. Opera, we know, is structurally deadly – notably to its women characters. Filmmaker Sally Potter (Thriller, 1979), anthropologist Cathérine Clément (Opera and the Undoing of Women, 1979) and opera singer and cultural theorist Elizabeth Bronfen (Over Her Dead Body: Femininity, Aesthetics and Death, 1992) have all in various ways pointed out that opera repeatedly kills women and renders homicidal violence aesthetic.

Potter made a film in which Mimi from Puccini’s La Bohème – having died at the curtain’s fall – returns as ghostly detective to find out why she had to die. Loving opera, but troubled by its misogyny, Clément reflected on this fact: “All the women in opera die a death prepared for them by a slow plot, woven by furtive, fleeting heroes, up to their glorious moment: a sung death.”

As the New York Times’ Paul Robinson writes: “Opera thus permits men to give voice to their homicidal misogyny, albeit in often disguised or distorted form”. Bronfen argues that the repeated connection of a beautiful woman with death functions to deflect of our fear of human mortality. The beautiful corpse displaces men’s own fear of death, projecting it onto a feminine image instead.

The Tarantino turn in opera productions betrays the unique aesthetic and troubling cultural mode of opera. Violence and passion are written and experienced musically, but also through the musical voicing of emotion. In providing the eye with explicit scenes, the audience is distracted from listening. The visual depiction drowns out the more subtle – but equally disturbing – sonic rendition of gender violence and deafens us to the orchestration of beauty and deadliness entangled.

While innovative staging of opera undoubtedly enriches and extends appreciation for this historic art form, gratuitous performances of sex and explicit violence fail to confront us with the most crucial issues. Through the mediation of embodied music, opera examines our capacities for violence, envy, jealousy, passion and indifference. It stages scenarios for our imaginative reflection, transforming the audience into listeners whose minds and bodies are moved by the vibrations of the voice – that human site of pathos.

I remain with Ed Gardner. Let them sing, and keep the blood and the sex off the stage.

For an alternative take on the William Tell controversy, click here.