The Chinese leadership transition last year, with Hu Jintao handing over to Xi Jinping, finally laid to rest Deng Xiaoping’s long-running maxim that China should “keep a low profile and hide its brightness”.

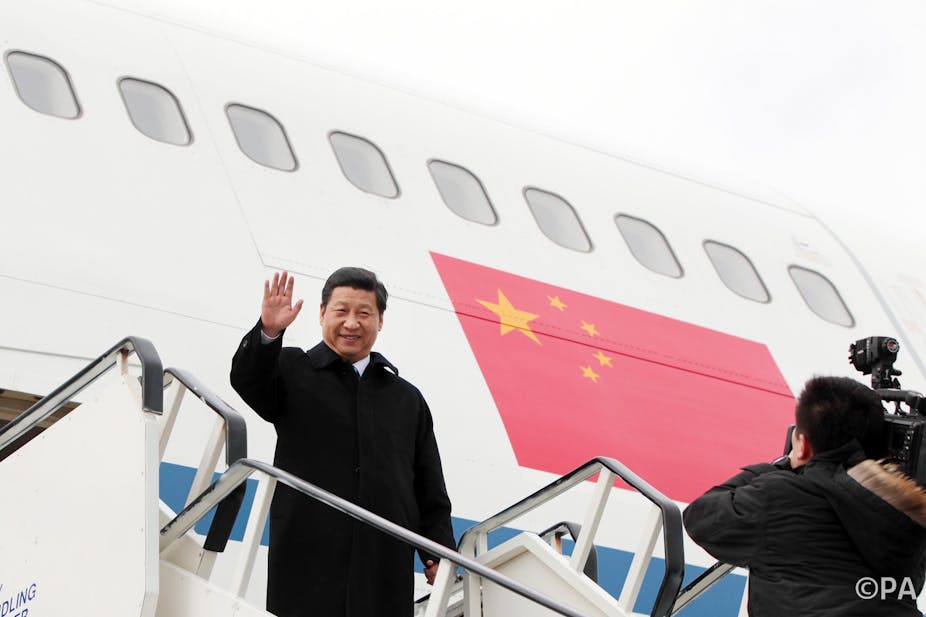

Evidence to that effect was on full display, for example, in Trinidad and Tobago in June this year, when Xi and the first lady, Peng Liyuan, touched down in the small, oil-rich islands for a state visit. As they strode down the gangway, they seemed somehow ostentatious, Peng’s turquoise attire matching Xi’s tie. Such a look would have been less remarkable had this been any other first couple.

Until now, perhaps due to the memory of Mao Zedong’s feared spouse Jiang Qing, Chinese first ladies have shunned the limelight – and by comparison to Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, Xi’s performance on the world stage is remarkably outgoing.

His extrovert manner is increasingly of a piece with foreign policy, as China leverages its influence in parts of the world where it had previously operated more tentatively. The country’s soft power is being felt more widely than ever, as are the knock-on effects of its domestic economic reforms.

Yet despite this outgoing appearance, we still know very little about the aspirations that guide the new leadership of the party; and we still have to glean what clues we can from official announcements – hence the importance of the Third Plenum’s communiqué.

Nothing to get excited about?

This announcement had been hotly anticipated for some months. There had been speculation that Xi’s sure-footedness at the helm, combined with the reformist credentials of his premier Li Keqiang, would allow the party to take sweeping measures to alleviate social inequalities and break down oligopolies. There were also hopes that Xi and Li would streamline China’s often contradictory foreign policy and better manage the country’s maritime disputes with Japan, the Philippines and Vietnam.

The climate of expectation meant that the Third Plenum, which convened just over a week ago, was expected at the very least to set out a bold agenda primarily for domestic change – even if few commentators truly expected it to spell out a coherent vision of China as an emerging superpower. The anticipation of groundbreaking decisions had been building for months, riding a wave of upbeat coverage in China’s state-controlled media. Independent analysts, for their part, argued that Xi would seem hopelessly out-of-touch if he were to under-deliver.

But despite predictions of a “promising” or “unprecedented” announcement, the Third Plenum communiqué has instead been received mostly with disappointment both at home and abroad. Specific measures are usually publicly announced only in the several weeks following plenary party conclaves, and the communiqué itself is sufficiently vague to allow for imminent surprises – but still, there is no truly surprising or dramatic news.

In the absence of major stories, what has subsequently hit the headlines in China is not empowerment for the private sector or better protection for individual property rights, but instead the establishment of a national security council – whose mandate and purpose are far from clear.

‘Feeling the stones’

Yet this vagueness and hint-dropping is nothing new. The communiqué’s approach follows exactly the sort of cautious reform rationale that has defined much of the past 30 years in China: policy making by trial and error.

The party’s approach to governing has long been an incremental one, known as “crossing the river by feeling the stones”. Communiqués like the recent one use opaque party jargon to conceal innovations that actually emerge on the ground over the course of a few years, while they are tried, tested and allowed to bed in.

In this spirit, the communiqué hedges considerably about how things will proceed. For example, it sets out to “straighten out the relationship between government and the market” by allowing the market to play a decisive role in allocating resources, whilst at the same time ensuring the party continues to command “all quarters” – hardly a bold statement for change.

More notably, the communiqué pays homage to the “achievements” of the Mao Zedong era at quite great length. Though hardly a surprise in view of Xi’s rhetoric in recent months, this homage to Mao is somewhat absurd. It not only defies the plurality of opinion and extensive programme of research into the complexities of the Mao era, both in China and in the West; it also sits very uncomfortably with what we know of Xi’s personal journey.

Xi, like the other princelings who now run the country, may have experienced a privileged early childhood in the Mao era, but many of his generation’s parents suffered brutal torment at the hands of the state. Yet the party’s nostalgic praise for Mao’s rustic mindset, issued even as rapid urbanisation is transforming China beyond recognition, betrays an ambivalence about the legacy of the reform era.

China dreaming

Against the backdrop of sluggish economic growth in the West and the failure of the Arab Spring, the conflation of the reform era with Mao’s legacy has become central to the CCP’s account of China’s relative success and international uniqueness. Running the last 60-odd years together into a coherent history has popular appeal at home, and might confer some patriotic legitimacy on the party in the intermediate term – but it certainly will not endear Xi’s “China Dream” to the developed world.

There is, as has been reported, an upside. The communiqué does hint (albeit broadly) at the gradual phasing out of some of the rigours of the one-child policy, and of “re-education” camps. The Plenum’s full decision hints at other changes besides, concerning judicial, rural-land and household-registration reform – measures that could (and should) make life a little easier for China’s millions of disenfranchised migrant workers, provided they are actually implemented.

State-owned enterprises may similarly be forced to transfer stock to external stake-holders in a bid to make them more accountable and have them pay back the central government their fair share in tax. The idea here is to level the economic playing field, so that less politically-connected private-sector businesses can compete more effectively in the marketplace and more easily protect their intellectual property rights.

But in the absence of specifics, we can only hope that these measures will be fleshed out and followed through before too long – and assess them on the merits of what actually happens, not what is tentatively announced.