The “homelessness crisis”, particularly in Melbourne and Sydney, has attracted renewed attention in recent months. While there are higher rates of unemployment for people who are homeless, many are working and homeless.

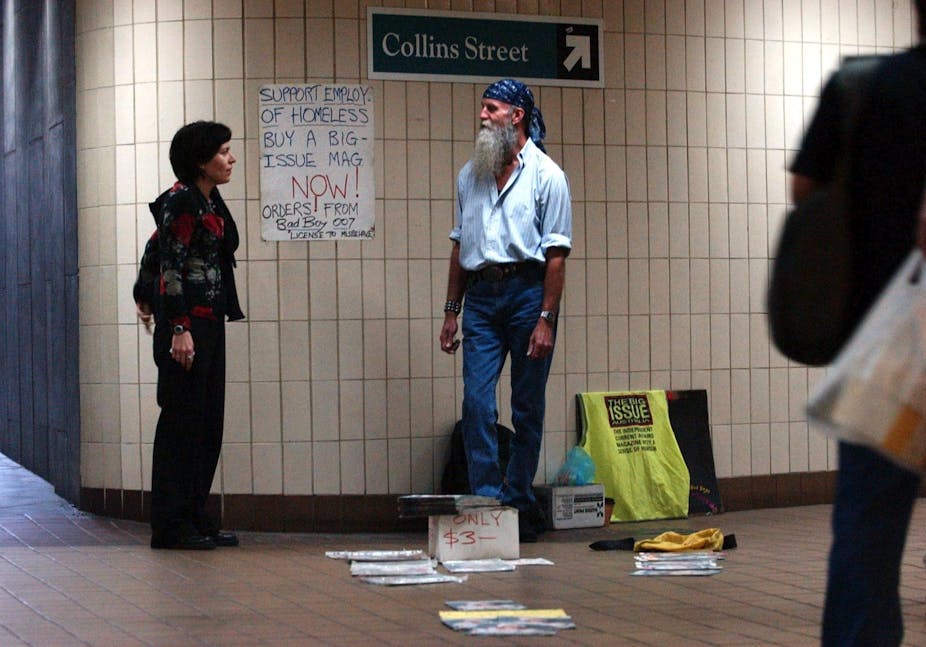

For the past two decades, the growing numbers of Big Issue sellers on city streets across Australia have perhaps been the most visible and public of the “working homeless”.

While The Big Issue is based on the idea of “a hand up, not a hand out”, little research has been carried out on its impact and sellers’ experiences. My research findings reveals the long-lasting effects of inequality and poverty and the impact of precarious employment and working conditions.

There is a need for more co-ordinated and comprehensive policy responses to – and resources for – homelessness, entrenched disadvantaged and long-term unemployment.

Further reading: Supportive housing is cheaper than chronic homelessness

Australia’s first social enterprise

The Big Issue – a homeless street press publication – was launched in 1991 in London and in 1996 in Melbourne. Premised on the importance of creating work for those who are homeless and long-term unemployed, its motto is “working, not begging”.

The Big Issue is part of a much larger global network of “homeless street press”, which has its historical roots in activist groups in the US. The Big Issue took the grassroots activist model and merged it with a business imperative to create arguably the first social enterprise: a business with a social purpose.

Social enterprises, a fast-growing sector in Australia, aim to respond to social problems with market-based business ideas and practices.

The Big Issue aims to be a self-sustaining business that engages sellers in “genuine” work. Sellers buy The Big Issue magazine for half the market price (at the moment A$3.50) and sell it on for full price ($7), thereby making $3.50 per sale.

As a model of social engagement it is incredibly popular politically. Every year, politicians and business leaders help raise the profile of the organisation by spending a few hours selling The Big Issue.

But what is it really like being a Big Issue seller? Does it provide a pathway out of homelessness and poverty? Do market-based solutions to homelessness and poverty work?

I spent some 18 months alongside 40 Melbourne sellers (and one ex-seller) to answer these questions. Most had been homeless at some point. Some were still homeless, while others had managed to secure private rentals or social housing. Most sellers remained hopeful of a pathway out of poverty, but few realised this.

What do sellers say about their work?

Money helps, but not enough

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Big Issue sellers welcomed the chance to work. Many had injuries, disabilities or other health conditions that meant more formal employment was out of reach. Others simply could not find work.

Being able to top up meagre Centrelink payments to help pay for rent, everyday basics, medical expenses, or even to save a little was welcome and in some cases life changing.

Sellers spoke of the dignity that working gave them – as a chance to demonstrate their commitment to working – and were grateful for the opportunity.

Yet, apart from a slim few, most sellers made very limited income. Some sold only two or four copies a day, thus earning no more than $14 for five to eight hours’ work. The most successful sellers scraped closer to the minimum wage, but only on the best hours of the best days.

The income from The Big Issue is very precarious – sellers can never be sure of what they’ll get. To make ends meet, many worked rain, hail or shine and through illness or painful medical conditions.

Relationships: good and bad

Sellers spoke powerfully of social relationships they made with regular customers, The Big Issue staff, and their local community. Having meaningful and positive interactions was central to the significance of their work.

However, sellers also spoke of the difficulty of the visible and public nature of their work. Sellers were aware people were judging them, their appearance and actions. Sellers sometimes struggled to put on a “smiley face” while managing the challenges and disadvantage of being homeless and poor.

At times, sellers had to manage negative interactions with the public, from sneers of “get a real job” to feeling lonely and ignored. They might just have one of the hardest sales jobs in the country.

What can we learn from Big Issue sellers’ experiences?

These experiences reveal the flimsy basis of the “lifters and leaners” rhetoric, which still persists in recent government welfare policy changes.

Punitive approaches such as welfare cards and drug tests have little grounds in research evidence, and do much to stigmatise and blame people for society’s inequalities.

Further reading: How history can challenge the narrative of blame for homelessness

Sellers’ experiences certainly do not support the presumption of “work-shy” benefit dependency. Many work five, sometimes seven, days a week in spite of their difficulties.

Sellers recounted multiple experiences of inequality. These range from waiting years for public housing and being moved on when homeless, to struggling to manage family and medical budgets on Centrelink payments and feeling dismissed by society as not contributing.

Their experiences offer a powerful insight into the everyday challenges of living in poverty and long-term unemployment in Australia. The effects of stigmatisation, social exclusion and disenfranchisement are powerful.

While homelessness is a complex phenomenon, its recent growth in Australia cannot be disassociated from broader social inequalities and poverty. This includes recent rises in long-term unemployment, underemployment, precarious working conditions, and need for more affordable housing.

My research indicates that being a Big Issue seller may provide avenues for meaningful work and social interactions, but does not offer secure pathways out of poverty and homelessness or into waged work. Market-based business initiatives are not an effective replacement for comprehensive government policy when it comes to structural inequality.

The experiences of Big Issue sellers tell us there is an urgent need to address inequality, unemployment and homelessness in Australia. A significant part of this is tackling the unequal and precarious labour market. Current policy responses to are not enough, and many serve to deflect the structural basis of poverty.

As a starting point, government can do much more through resourcing social and public housing, women’s refuges and homeless services and by increasing the Disability Support Pension and Newstart Allowance, which has not increased in real terms in 20 over years.

Beyond this, there is a need to address the lack of opportunity for meaningful social engagement, dignity and work for those excluded from formal employment.

Jessica Gerrard is author of Precarious Enterprise on the Margins: Work, Poverty and Homelessness in the City.