Housing affordability has quickly become a crisis in most metropolitan areas of the world.

People in developed countries like Canada and the US have been feeling the burden of rising housing prices. This affects all people from different economic backgrounds, including the upper-middle class.

The story is no different in the world’s fourth-most-populous country, Indonesia.

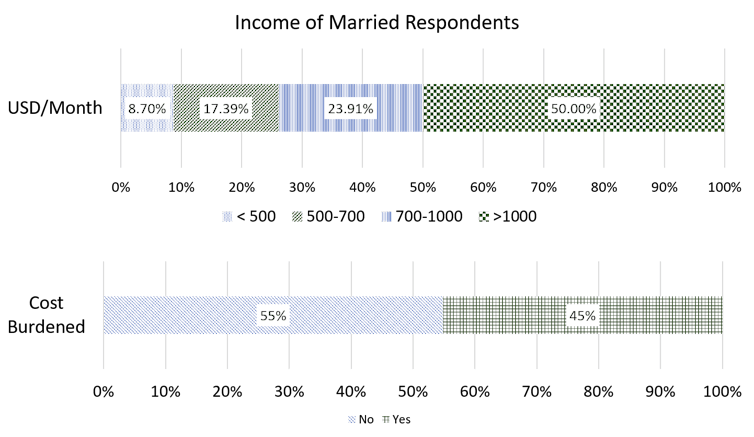

The latest research shows that 28 out of 62 randomly sampled respondents, or 45% of them, reported they were burdened by housing expenses such as mortgage and utilities.

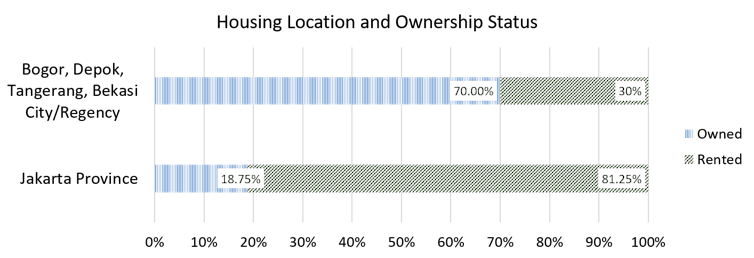

Housing in Jakarta is so expensive that 80% of the respondents are in short-term rental houses.

Affordable housing is important for the nation’s economic growth.

The World Bank’s 2020 report showed the middle class in Indonesia contributed to 50% of the nation’s total consumption. The average individual spent Rp 1.2-6 million (US$85 to $424) a month — including for housing.

The increasing housing-related expenses may hurt the middle class’s purchasing power, which could jeopardise Indonesia’s economic growth.

Therefore, I suggest three policy changes to curb an impending middle-class housing crisis.

First, strengthen the role of government collectives to regulate housing supply and demand.

The collective governance of Greater Jakarta, which comprises the cities of Bogor, Depok, Bekasi in West Java and Tangerang in Banten, as a conurbation or a merger of multiple neighbouring urban areas is critical.

Bogor, Depok and Tangerang regions have existed in supporting roles to Jakarta’s economic activities but consolidating urban settlement planning has not been one of the priority programs.

Local governments in the Greater Jakarta area should understand that each region’s urban development interests are too dependent on each other to be governed entirely independently.

The other regions should carry some of the load of Jakarta’s housing backlog. Although the role of private developers is critical, local governments must create better policies to ensure the development is sustainable.

These policies may include stricter supervision of the development of social housing and land use planning.

In London, its city government strengthens its planning system by creating more affordable housing and encouraging build-to-rent schemes so half of London homes are affordable to all.

In addition, we’ve not yet have enough discussion of long-term planning for the conurbation. Solutions to the housing crisis must start there.

Second, Jakarta must consider legitimising private rented housing schemes.

The fact that 80% of respondents who lived in Jakarta were in short-term rental should be an indication of the need for the government to draft policies on rental housing.

Currently, although regulations exist for public or government rented housing, neither the central government nor Jakarta governmental office has any policy on private rented housing.

Adding to the absence of regulations on rent houses, there is still a widespread stigma that renting house is a waste of money. This is why people are much more willing to live 40-50 km from their workplace, spending money, time and energy on commuting, than rent a house that is closer to work.

Difficult as it is to change the stigma, the least the government could do is to devise a policy that will institutionalise and formalise renting houses.

This works in Singapore, which mandates registration of owners and tenants and has separate regulation for landed and non-landed residential. This regulation ensures the legal security of tenants and positions renting as a viable residential option.

Long-term rental housing policy is not a rare occurrence in many big cities all over the world. Metropolitan centres like London, New York, Amsterdam and Singapore are all dealing with a surplus of residents and limited permanent housing options, so they implement policies and regulations to ensure the legitimacy and security of rental schemes.

In Jakarta, boarding rooms and rental houses simply exist without sufficient permits and regulations. This puts tenants and renters in danger of exploitation by business in bad faith.

This condition also worsens the stigma that rental houses are temporary and not desirable.

Third, the government should provide more middle-cost housing supplies through public-private partnerships and create financing schemes targeted to the middle class.

The government must take better control of housing market prices by building more middle-cost housing units and expanding the price cap to include middle-income prospective buyers.

The current public housing and housing subsidy program is dedicated to those with a monthly salary of no more than Rp 8 million (US$567), thus excluding Indonesia’s middle-class people.

The skyrocketing house prices are caused by the high demand and shockingly low supply of affordable housing in desirable areas.

Jakarta’s house price inflation has spread to other regions. Soon living in Tangerang or Bogor will no longer be affordable for many, unless the government takes control of housing development policies and land use regulations.