Ordinarily, people face far greater punishment each time they are caught committing another crime. Federal sentences for recidivists go up dramatically.

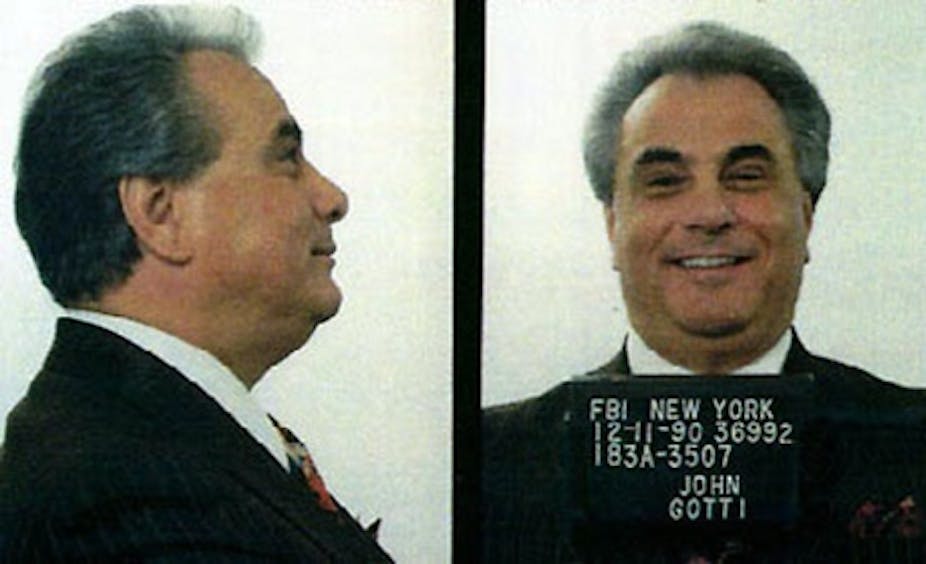

But like green-shaded teflon dons – mobster John Gotti’s nickname for managing to stay out of jail – the largest banks have been repeatedly prosecuted over the past decade and yet have so far avoided any harsher consequences. Instead they’ve received “deferred prosecutions” or non-prosecutions that trade criminal charges for promised reforms and criminal fines.

Now, as a new wave of bank prosecutions threatens to crash over Wall Street, it is time for clearer rules for recidivist banks and corporations more generally. Last week, the Department of Justice seemed to be finally leaning in that direction when it issued warnings that it “will not hesitate to tear up” corporate settlements if they are violated.

Wall Street recidivists

Prosecutors are now investigating major banks for colluding together on foreign currency rates, following on the heels of prosecutions relating to money laundering, to violating international sanctions and to gaming key interest rates. Last year, Barclays and UBS had agreements with prosecutors extended for another year, pending further investigation. If the same banks have committed fresh crimes in such a short period of time, the banks should be treated as what they are: recidivists.

But in the past, the largest banks have almost without exception avoided convictions and sentences entirely, entering into deferred and non-prosecution agreements with prosecutors.

These lenient deals have become notorious. Eight banks have received multiple out-of-court deals of this type since 2001. UBS has settled three prosecutions in just the past five years. AIG, Barclays, Credit Suisse, HSBC, JPMorgan, Lloyds and Wachovia have each settled two cases. Some of these banks, despite agreeing to settle a single “case,” admitted conduct ranging over multiple operations over many years.

Endless strikes

Sweetheart deals with banks can disguise recidivism. The non-prosecution deals may not count as “strikes” – as in three strikes and they’re out. The terms typically say the company must not engage in additional crimes for two or three years, but often only if the subsequent wrongdoing is a “similar” offense.

What counts as “similar” is apparently open to interpretation. Few recidivist banks were treated more harshly the second or third time around – such as by receiving a criminal conviction – and some were treated more leniently. Under these deals, a bank’s lawyers could fairly complain, were a conviction considered, that they had no idea the bank might be treated as a repeat criminal, since they negotiated the deal precisely to avoid one.

One bank deal did rankle a federal judge. Barclays entered a 2010 deferred-prosecution agreement for violations of economic sanctions against countries such as Burma, Cuba and Iran. At the time, Barclays avoided a conviction, but paid a $300 million fine and — critically — agreed not to violate any US federal laws for two years.

Yet just two years later, Barclays was back in court again, having been caught with its traders colluding in setting a key interest rate. This time, Barclays received a more lenient non-prosecution agreement, with prosecutors citing its “extraordinary cooperation.”

The judge who was still supervising the 2010 agreement asked for a good explanation why the collusion didn’t violate the earlier agreement – and why Barclays wasn’t treated more harshly – but ultimately he agreed to dismiss the case.

Solutions: convictions, sanctions, sentencing guidelines

One solution to this problem is to put convictions on the record: banks should routinely be convicted for serious crimes, as Credit Suisse and BNP Paribas were last year.

If banks are convicted, a judge can punish a recidivist for violating probation. Judges can also simply decline to approve deferred-prosecution deals for recidivist banks.

A second solution is for federal prosecutors to strictly hold banks to task for violating earlier agreements. Last week’s DoJ warnings suggest they may be poised to do so informally in the months ahead. But banks should be on notice if the policy has changed. Clear Justice Department policy should require more severe sanctions for a recidivist bank or corporation, just as for individuals.

A third solution would be legislation or sentencing guidelines to adopt clearer and stricter rules for corporate recidivism generally.

“There is no such thing as too big to jail,” Attorney General Eric Holder assured us last May. I was not convinced, however, that the problem had become imaginary and titled my book exploring corporation prosecutions, “Too Big to Jail.”

In the past year, the Department of Justice has argued that record-setting fines — including the largest-ever bank fine against BNP Paribas — prove banks are no longer above the law. Yet without more meaningful reforms, “too big to jail” endures. Even with record fines, there remains the larger question: do prosecutions fundamentally change the banking culture, or will crimes remain a cost of doing business?

If the likes of the largest banks are not held strictly accountable despite repeat crimes, then calling slaps on the wrist criminal punishment distorts the very notion of what is criminal.