Two new tools for measuring and visualising problems in our rental housing system are in the media this week. They have similar names – the Rental Affordability Index (RAI) and the Rental Vulnerability Index (RVI) – but use different methods to offer distinct but complementary perspectives. Together they reveal that almost nowhere in our capital cities can low-income households – and those on average incomes in Sydney – afford the median rent. Mapping rental vulnerability reveals households in regional areas are struggling too.

The RAI is a project of National Shelter, the peak housing NGO, and SGS Economics and Planning. It gives us a bird’s-eye view of rental housing costs over most of Australia. It does this by showing how affordable the median rent (the midpoint of all rents) is – or isn’t – relative to incomes in each postcode.

An alternative approach considers where and in what proportion renters are actually in stress. We might also consider a range of other factors that indicate where and in what proportion renters are vulnerable to problems in accessing and keeping decent, secure housing. This is the approach we’ve taken with the RVI.

What does the RAI tell us?

Affordability is a relative concept – it is about costs relative to incomes. The RAI considers median rents higher than 30% of a household’s income to be unaffordable. The index shows other grades either side of this benchmark (very affordable, very unaffordable) too.

This is consistent with a widely used benchmark in housing policy, often known as the “30/40 rule”: housing costs should not exceed 30% of income for households in the lowest 40% of incomes.

The rationale is that when low-income households have to spend more than that on housing, they start to go without other things – meals, health care, outings – that they reasonably ought to have. For this reason, low-income households in unaffordable housing are said to be in “housing stress” or “rental stress”.

The RAI looks at median rents, not the rents individual households are paying. This means it doesn’t tell us where or how many households are actually in rental stress. But it does indicate where renters face different degrees of pressure, in terms of either rents or constraints on the size, quality or location of dwellings.

So, looking at the affordability of median rents for a number of typical low-income households – single and couple pensioners, single people on benefits, single-parent part-time workers – the RAI shows that almost nowhere in Australia’s capital cities is the median rent affordable for them.

The RAI also applies the 30% benchmark higher up the income scale. Even for average-income renters, all Sydney postcodes – except for Mt Druitt and in the Blue Mountains – have median rents that are unaffordable or worse.

Of the capitals, Sydney’s affordability problems are deepest and spread furthest, but much of Melbourne and Brisbane is unaffordable to average renters too. Outside the capitals, most of the regions are affordable.

The quick takeaway from this perspective would be support for policies to increase the supply of affordable rental housing, particularly in our capital cities. These measures would include:

building more social housing

changing planning rules to allow more residential development

using inclusionary zoning to ensure a proportion of new development is kept as affordable rental

making greater use of land tax, including on owner-occupied housing, to ensure land owners don’t speculatively sit on development opportunities.

What does the RVI tell us?

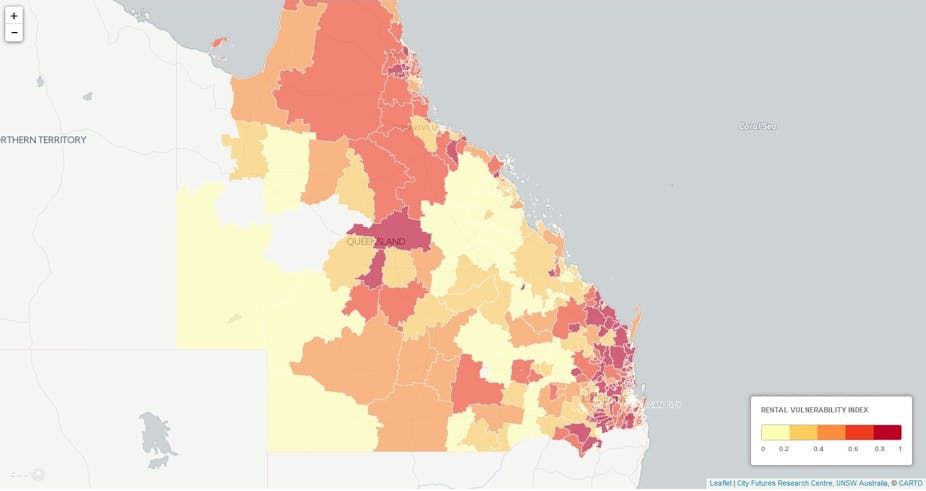

For a different perspective, the City Futures Research Centre produced the Rental Vulnerability Index (RVI) for Tenants Queensland. This shows (only for Queensland, at this stage) a range of “housing system” and “personal” factors that we know, based on a wider body of research on housing and legal needs, indicate vulnerability to housing problems.

The housing system indicators include: rental stress, availability of rental housing that is affordable on local incomes, social housing and marginal tenures such as boarding houses, as well as personal indicators including unemployment, low education, disability, single-parent households and both young and elderly renters.

As well as mapping each of these indicators, the RVI uses principal component analysis. This enables us to look across the indicators to see where they cluster together as a generalised “rental vulnerability”.

Mapping this out we see that rental vulnerability in Queensland is highest in the regions. In particular, it is high around Bundaberg, Fraser Coast and Gympie, with a band of vulnerability skirting the regions west and south of Brisbane. Cairns also has several highly vulnerable postcodes.

These places have high rates of unemployment, disability, low education and older people in rental housing. They also have high incidence of rental stress – even though median rents are low compared to Brisbane.

By contrast, Brisbane generally scores quite low on rental vulnerability. This isn’t because there aren’t any vulnerable households there – there are. But their presence is masked by renter households who are doing well in terms of income, employment, education and other indicators.

There is a substantial body of research on the “suburbanisation of disadvantage”. This is the phenomenon of high housing costs pushing out, and shutting out, low-income and otherwise disadvantaged households from city centres. The RVI indicates that this process, at least in Queensland, is extending into a “regionalisation of disadvantage”.

So what can we do about this?

The takeaway from this? Housing problems are multidimensional and extend beyond the capital cities.

Regional areas have a pressing need for services – such as tenants advice services – that give vulnerable households material assistance in dealing with housing problems.

But more than that, we need to build up the economic and social capital of these places – so that they offer greater opportunities for the vulnerable households who are concentrated there – just as we need policies to increase affordable housing opportunities in our cities.