There are more black African students from poor or working-class backgrounds at South Africa’s universities than ever before. But research shows that very few of them actually finish their degrees. Many drop out at undergraduate level. This leaves them and their families in debt and dashes their hopes of climbing the economic ladder.

The same research shows that the socially and economically privileged counterparts of these students fare far better. It is this structural inequality that lies at the heart of student protests that rocked the country’s universities in late 2015 and early 2016. Universities must challenge this inequality if higher education is to experience genuine social change.

Of course, any such response will require a significant injection of resources, such as more teaching staff being made available to undergraduate students. But not all aspects of inequality are rooted in physical resources. Plenty can be achieved if universities start dismantling the deep-seated assumptions and hierarchies that maintain inequality within their structures.

I have conducted research that draws on students’ own experiences to try understand how universities can cultivate the conditions that enable equal participation, regardless of race or economic status.

The value of student experiences

All individuals bring a number of advantages or disadvantages to university as their bundle of resources. Ideally, they should be able to draw from this bundle to adapt and succeed. But it can also hinder them.

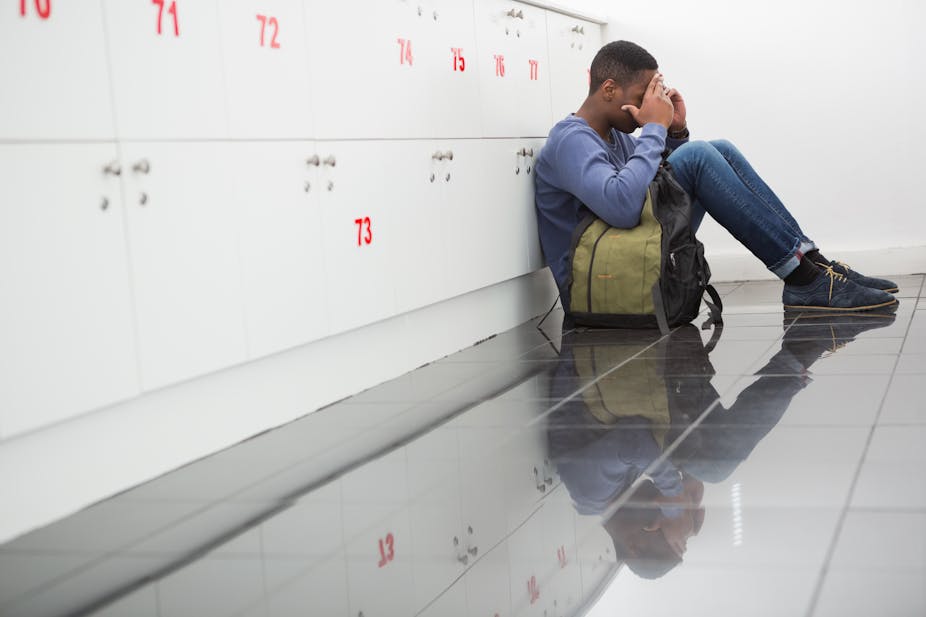

Students are marginalised when they have to negotiate factors that complicate their academic success and social integration. These include belonging to a low-income household, being historically excluded because of race, being a woman, identifying as a sexual minority or living with a physical disability.

I interviewed eight undergraduates at a South African university that historically catered only for white students. They were all the first in their immediate families to attend university.

These students arrived at university with a precarious and less-valued bundle of financial, academic and social resources. Most were from low-income families, with one or more unemployed parent or guardian. Financial pressure made it difficult for them to know where money for the next meal, rent payment, taxi fare or textbook would come from. In the privileged, middle-class university space they felt anxious, ashamed and stressed. They internalised their struggles to cope as individual failure.

My research used a “capability approach” to assess students’ experiences. This evaluates how available resources are converted into opportunities to achieve valued outcomes, or what are called “capabilities”. This could mean, for example, interrogating whether attending university automatically equips the student to become critically engaged in acquiring knowledge. If the student is only attending lectures and regurgitating information, has deep learning taken place? What structures need to be in place to ensure that the resource – in this case, education – is converted into a meaningful academic outcome for vulnerable students?

In other words, resources are an important but insufficient measure of equality. Structural inequality has not been adequately addressed if the environment does not offer equal opportunities for all students to convert their resources into valued outcomes.

The students we interviewed came up with several recommendations that might help universities become more inclusive, equitable environments.

Doing things differently

The students had three main concerns:

they wanted spaces in which to build positive relationships with their lecturers;

they felt there should be more sustained platforms for voicing their frustrations without being dismissed as emotional or ignorant; and

they said it was not helpful for lecturers to constantly highlight poorer students’ failures.

These students felt alienated, fearful and silenced. They said most lecturers weren’t open to sharing the implicit lessons and insider information needed to navigate any university experience. For example, knowing where to find free online sources, or unspoken “etiquette” about approaching or communicating with lecturers. Their more privileged peers were confident enough to approach lecturers, and so found this information more readily available.

Students also complained that there was no real chance for them to have fertile dialogues with teaching staff about their academic challenges. Lecturers should strive to make their classrooms a place where critical engagement with knowledge meets a humane approach to vulnerable students’ challenges. Some lecturers may need to rethink their approach to daily teaching. They could even take the process further by spending an hour a week mentoring a first-generation student.

There’s also a broader need for spaces where lecturers and students can collaborate in ways that challenge the traditional meritocracy of a university environment. One example of this would be involving undergraduate students in research projects so they can develop academic skills.

The students we interviewed struggled with being constantly reminded of their struggle and academic failure. They found this demoralising and it created doubt in their ability to succeed. To overcome this, lecturers should recognise the capabilities and resources these students bring to university. Lecturers could foreground students’ agency and resilience instead of reminding them of what they cannot yet accomplish.

Creating equitable universities

There is no need for universities to wait for more physical resources. All of the work I’ve described here can begin immediately. These suggestions can go a long way towards making universities more welcoming, equitable environments for disadvantaged students.

Author’s note: All of the references in this article to race reflect persistent post-apartheid racial classification.