The ongoing battle between cosmetics company Lush and internet retailer Amazon is starting to give off a distinctly unsavoury odour. At the beginning, many supported plucky little Lush as it sought to stop Amazon from flogging lookalike bath products when users search for the word “Lush” on the site. Now it is starting to look like the consumer is being left behind as two companies exchange tit for tat.

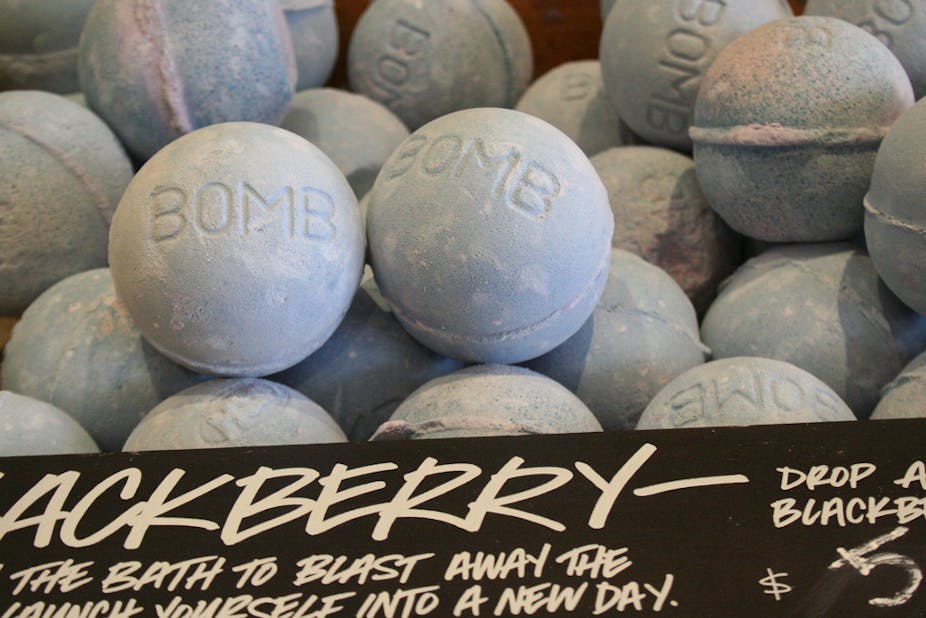

If you type “Lush” into the search bar on Amazon.co.uk, a list of thousands of products is returned. Most of the top results are bath products by Bomb Cosmetics, a fact that is causing a great deal of consternation for Mark and Mo Constantine, the owners of Lush.

The Constantines have always refused to sell their products on Amazon.co.uk and have taken the internet giant to court in England over its continued pushing of products similar to theirs. Lush’s reputation has been built around “ethical trading” and the Constantines have said they don’t agree with the way Amazon does its business. But the actual court case does not make the specifics of their objection entirely clear.

That’s because this case is not, and should not be about ethics. However much we might admire the politics of Lush or resent how Amazon operates, their respective reputations are not really the point here.

The nub of the issue is on the one hand, the extent of the control the Constantines can exert over the use of the word “Lush” in association with bath cosmetics when it is registered as a trade mark and, on the other hand, Amazon’s business model. Amazon relies on being able to offer a wide range of products, the keyword references to which are built up through intelligence gathered from searches performed by consumers when looking for goods.

And it’s not the only company that depends on this model. Internet companies the world over will be taking note of this case. This is just the latest in a long line of disputes concerning trade marks and keyword advertising. They happen when one company uses keywords that might be registered trade marks in order to draw the attention of customers to their goods and services or to the goods and services of a favoured third party.

Google, eBay, Interflora, Marks & Spencer and numerous others have all been involved in one way or another in this type of litigation. LINKS

As sticky as a half-used bath bomb

What sets the Lush case apart is that Amazon was found to have been using the word “Lush” in its commercial communications, whereas eBay only acts as an online marketplace for trade marked products.

The question here was whether Amazon’s use implicated one of the functions of a trade mark, such as by identifying the original source of a product, advertising it or affecting potential investment in that product. The court said there was no indication that Lush products were not available for purchase on Amazon. And given the consumer had been informed, via a drop down menu, that “Lush bath bombs” were available, an average consumer would not “without difficulty” know that the goods that show up in a search do not originate from the brand Lush.

That the appearance and branding of Bomb Cosmetics products made them look similar to Lush products only makes it harder for a consumer to conclude “without difficulty” that the goods they were being shown were not connected with Lush.

The advertising function of the trade mark came in to play when the court decided that Amazon’s use of the trade mark would dent Lush’s ability to attract custom. And even the investment function of the trade mark was implicated because of the (unspecified) problem that Lush had with Amazon’s reputation.

David, Goliath and you, the consumer

This is undoubtedly not the last word on the matter. Amazon will appeal the judgement. And there are issues arising from the case that have wider implications and will need to be worked out.

Trade mark law exists specifically to protect the consumer but the way these disputes play out is an odd state of affairs indeed. The consumer has no standing to sue to protect their interests and the battles are fought between traders.

One way the focus is kept on the consumer is the concept of consumer confusion. In this case that test has become a question of whether the consumer can tell “without difficulty” the origin of the goods.

I may be unscientific in my approach, but I did not for a minute think that Bomb Cosmetics products originated from Lush when I saw them on Amazon. In other words, I was not confused.

The reasoning of the court in this David and Goliath case is also a little light in relation to how exactly either the advertisement and investment functions have been infringed. Has Lush really suffered financially from this situation as much as it says? It’s hard to say.

It may be that fuller consideration should be given to the worries that arose around what the impact would be on the consumer if Amazon’s business model has to change as a result of its run in with Lush.

We now live in world in which online shopping is the norm and many of us rely on Amazon-like businesses to deliver the service we have come to expect. We have to ask, therefore if it’s in the consumer’s interest to change the way these sites operate to protect companies such as Lush, however laudable their ethical standards might be.

While, as was said in the case, these concerns should not allow Amazon to run “rough shod” over intellectual property rights belonging to third parties, it does force us to focus on the central question as to what the trade mark system is for if, as a result, the consumer is disadvantaged.

Lush’s latest move has been to register Christopher North, the name of Amazon’s managing director in the UK, as a trade mark. There are plans for a range of products under the name using the tagline “rich, thick and full of it”.

While this has generally been portrayed in the media as an amusing next step in the battle between the mismatched adversaries, the danger is that the move will detract attention from one of the key challenges epitomised in this case. Trade mark law is supposed to protect the consumer and we need to take a long hard look at how technological challenges change the way we do that.