“Leathermen” are gay men who wear leather clothes that draw inspiration from masculine institutions like the military, the police, and motorcycle gangs. They also take great pride in their muscular bodies, dressing in leather to cultivate an image of “hypermasculinity” – a term that’s usually used to describe how some heterosexual men look and behave to prove that they are “manly”.

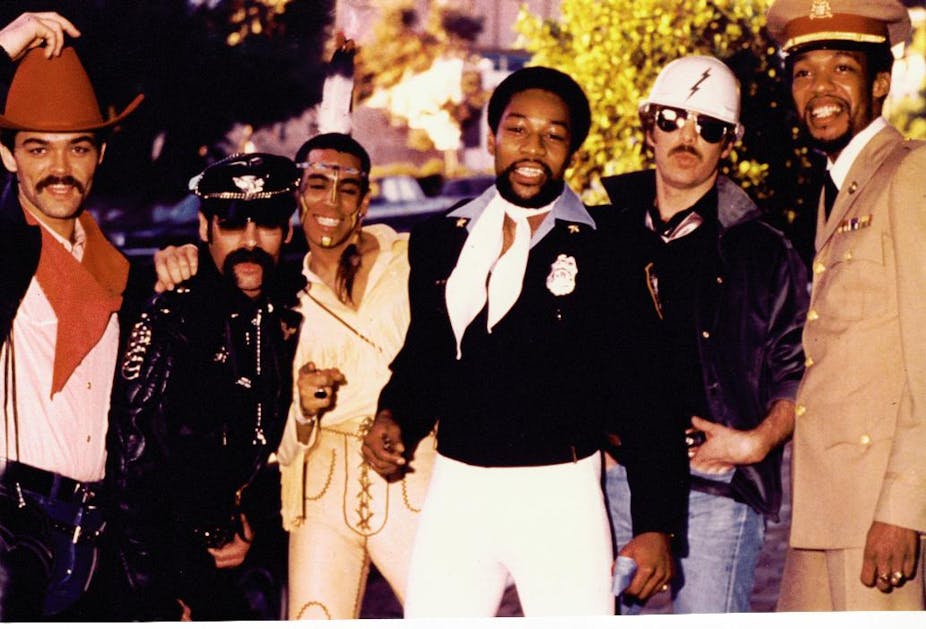

Leathermen are attached to a thriving subset of gay and lesbian subcultures all over the world. The “leathermen look” is often referenced in popular culture: think Glenn Hughes from the 70s disco group, the Village People; Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs; Lady Gaga’s video for “Bad Romance” and Madonna, who is the most ubiquitous referencer of the “leathermen look”, from videos to world tours.

Leathermen are tacitly accepted by the gay and lesbian “movement” because, after all, they are gay. However, mainstream gay and lesbian communities tend to be more sceptical about leathermen’s sexual practices. These are rooted in Bondage, Discipline, Sadomasochism and Masochism (BDSM); this kind of sex is generally viewed as abnormal by society at large, bar the “gentle whip” and “naughty spank” popularised by the Fifty Shades of Grey series.

In a recent piece of research I show how leathermen in South Africa finally became visible with the advent of Facebook in 2009. Prior to the advent of Facebook they were hidden from society at large but thrived as an underground subculture. Academic John K Noyes argued that historically in South Africa, the most active BDSM community was the white gay male community.

They were allied to the gay and lesbian movement (they were participants in Pride marches from the outset). But it became complicated. That leathermen enjoy “men only” spaces and the most visible leathermen communities are white men does not sit well with South Africa’s non-racial rainbow gay and lesbian movement.

Marlon Brando

Internationally, the leathermen “look” can be traced to post-World War Two motorcycle clubs in the US. Returning servicemen, who were homosexual, resented homosexuality being associated with femininity. They started dressing like members of motorcycle gangs. Over time other leather objects from the military and police were incorporated to achieve the “leatherman look”. These include biker’s jackets, breeches, chaps, pants, knee-high biker boots, harnesses, cuffs (biceps and wrists), belts adorned with motorbike insignia, Sam Browne belts, shirts, ties, gloves and Muir caps (also known as the Master’s hat).

A young Marlon Brando dressed in biker leather in the 1953 American film, The Wild One, epitomised the look best.

These leathermen did not want to be associated with other gay men and managed to pass as “real” men at a time when homosexuality was outlawed. Homosexuality was only “legalised” in 2003, and in a post-war America homophobia was particularly virulent.

The HIV crises of the late 1980s and 1990s decimated many leathermen communities in the US, most specifically in San Francisco.

One way for the community to show unity was by holding a pageant where the presentation of leather was foregrounded. This has become an institution in leathermen subcultures worldwide, South Africa included; it is the cultural highlight of the year for these communities.

Rainbow pageant

However, back in 2015 South African leathermen’s annual leather pageant was seen as being too white and too male. A breakaway pageant group was set up to reflect the diversity of the country’s gay and lesbian movement. The breakaway group held its own rainbow pageant, where the winners were a white leatherman and a black leatherwoman respectively.

The winners were lauded in popular gay and lesbian websites as Africa’s first “true” leatherfolk. However, “rainbow leather” lasted but a moment and has never been heard of again.

The reason for this I argue is that the strong contestation over the image of “gay leather”, as reflected in the pageant posters on Facebook, is about “the public” consumption of these images and what they say – not about leathermen, but about the gay and lesbian community by association. The gay and lesbian movement did not want to be associated with the “underbelly” of the leathermen scene, the sex, the drugs, the cruising and the promiscuity.

The purist leathermen, however, thrive on members’ only social media cites. They’re once again hidden from view and disowned by the gay and lesbian movement.

It’s true that leathermen in South Africa are mostly white, male and hypermasculine. But internationally, the leathermen community is the same – despite its membership being open to all gay men. And just because leathermen of colour are not visible doesn’t mean they don’t exist. Leatherwomen worldwide have also set up their own pageants and chapters, often in alliance with leathermen.

So why are leathermen in South Africa sidelined and even rejected? In my research I argue that this group is a source of shame to the assimilationist and lifestyle orientated gay and lesbian movement in South Africa, where marriage is viewed as the pinnacle of citizenship. The leather, the weird sex, the men only spaces, the bulging muscles and crotches are just too much for the larger queer community.

Archaic culture

The leathermen subculture is not understood in mainstream communities (perhaps only as part of deviant BDSM). It’s also misunderstood in gay and lesbian communities. That’s because it is seen as an example of an archaic culture that no longer has a place in mainstream gay and lesbian communities in post-apartheid South Africa.

This is a pity. There is much to be learnt about masculinity and gender from leathermen.

As a subculture, leathermen achieve their “manliness” in opposition to heterosexual hypermasculinity. They conduct their sex in safe and consenting environments, develop muscular bodies to attract other men and wear leather clothes that draw inspiration from the most masculine of heterosexual cultures – all without enacting the violence often associated with such cultures.

Leathermen actually expose the myth of hypermasculinity by refusing the violence and aggression which is normally attached to it. Instead, they produce their own cultural meanings of masculinity and gender.