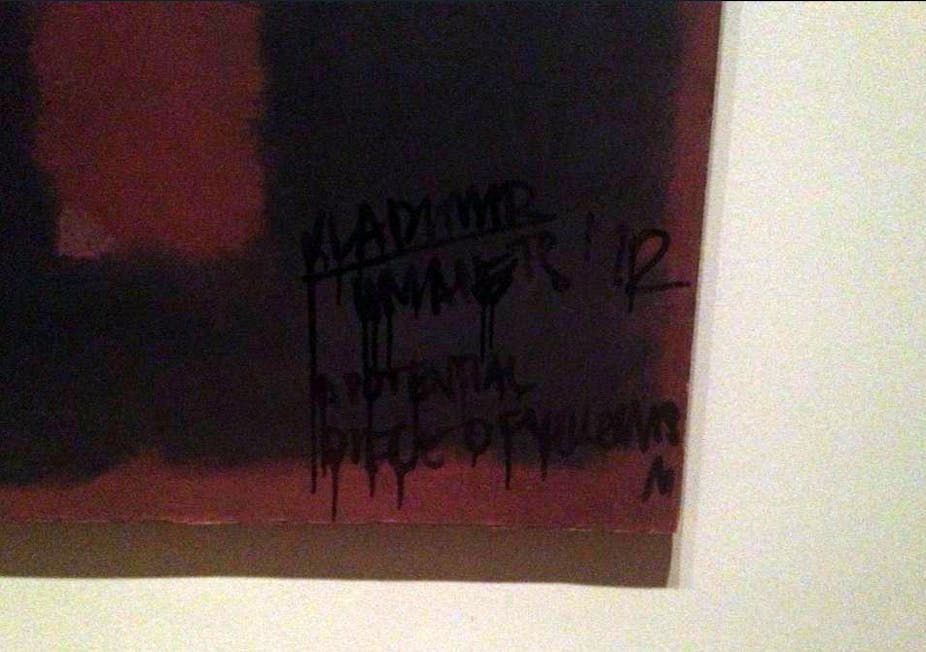

Vladimir Umanets, who scrawled his signature on Mark Rothko’s painting Black on Maroon in the Tate Museum this week, is not the first artist to deface an established artwork.

In 2003, Jake and Dinos Chapman wrecked a famous suite of Goya etchings called The Disasters of War. Though actually a more irreversible act of vandalism, the Chapman desecration — which they provocatively called Insult to Injury — was legal. As the brothers had legitimately bought the original works, the prints were technically theirs to destroy.

Sneaking into the Tate with graffiti equipment, on the other hand, Umanets committed a crime. Alas, what defines the crime isn’t the offence to art or the cultural patrimony — however grave it may be in ethical terms — but an infringement of property rights. It becomes a crime because the Rothko painting did not belong to Umanets. If he possessed the work, the tagging would be legal. By a similar logic, it is usually legal to raze works of architecture, provided that you own them. Demolition is a normal practice even among universities.

If facing court, Umanets may want to claim that his gesture was intended to deconstruct “art-as-property”. He may thus have the honour of historically revealing how much the autonomy and meaning of art are dependent upon ownership. This critique of property could be linked to the ideas of philosopher Peter Singer, who has complained that the price of artworks is immoral.

The appeal to an avant-garde critique may not impress the court, which is likely to consider such arguments Jesuitical. Besides, Umanets has already suggested that the Rothko will go up in value thanks to his moniker, an appreciation which negates any anti-materialistic argument.

His swagger is more credible than his philosophy. Albeit capriciously, he will contribute to the celebrity of the painting, almost as much as a theft would have done, which has the paradoxical effect of increasing the value of artworks.

The worst consequence of the crime may be the cost of the inevitable increase in security measures. The diligent conservators at the Tate will undoubtedly restore the work if it were stable to begin with; the public will once again enjoy the Rothko and the dead artist’s moral right of integrity will be protected. The longer term damage is the outlay on stricter invigilation, turning galleries into prisons, and making us feel that art is fragile and vulnerable rather than splendid and enduring.

Is there a moral dilemma in condemning Umanets and dismissing any creative intentions that the artist may have nurtured? Can we ever credit an act which is illegal but still ethically or artistically motivated? And if so, what is the test and how would Umanets fare when examined by the necessary criteria?

We feel like valorising illegal actions when we do not agree with the law or when the transgression seems more visionary than the interests that prohibit it. An example might be graffiti in inner-city laneways. Though a crime resented by many, the lawless spray is adored by others and used in advertising to heighten the prestige of bohemian neighbourhoods.

Umanets is likely to have a flimsy defence for a concrete offence. He might get a fine with his rebuke. All crimes are unsettling; but if only art-lovers are upset, the matter will be put down to a nutter’s whim in the confusing name of art. It’s even possible that the whole matter will be suppressed, for fear of publicity further endangering the collection. The Tate already lost two Turners in the 1990s and will not want to send out an invitation to pranksters to tag further artworks.

Umanets ingeniously invoked Duchamp’s signature of a urinal, which greatly inflated the price of the humble porcelain. If Umanets’ scrawl adds any value to the Rothko, it will not be because an author has been added to a mass-produced object, but because an unauthorised Oedipal artist sought to break the aura of a work already overwritten with adulation.