Foundation essay: Our foundation essays are longer than usual and take a wider look at key issues affecting society.

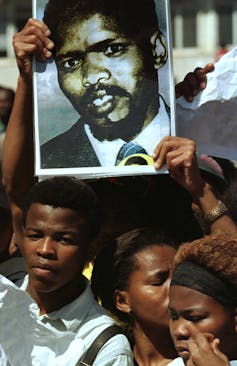

Peter Gabriel’s song characterising the influence of Steve Biko is as apt today as it was in the 1980s:

You can blow out a candle but you can’t blow out a fire. Once the flames begin to catch the wind will blow it higher.

The 41th anniversary of Biko’s death this month comes in the wake of high-pitched invocation in South Africa of the Black Consciousness philosophy he espoused.

Interestingly, the philosophy appears to have gained traction largely among the country’s black youth born after the end of apartheid in 1994. The appeal of Black Consciousness among the so-called “born-frees” is reminiscent of the way it influenced the generation that took part in the liberation struggle.

Is this a coincidence of history or a confluence of historical verities? Black Consciousness is a transcendence that connects generations, which in Frantz Fanon’s watchwords in The Wretched of the Earth:

Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfil it or betray it.

Born-frees and struggle generation

Political scientist Robert Mattes describes South Africa’s freedom struggle generation as that which, through the Soweto uprisings, brought to “an abrupt end in 1976, white confidence and African quiescence”. This is the generation of those who turned 16 between 1976 and 1996. It experienced the wrath of apartheid.

The first inclusive vote in 1994 marked the end of, according to Mattes, “a long trauma of protest, struggle and violence”.

As Mattes further explains, the born-frees refer to those who, starting in 1997:

… move through the ages of 16, 17 and 18 and enter the political arena with little if any first-hand experience of the trauma that came before.

Some characterise born-frees as who were born in 1994 and voted for the first time in the 2014 general elections. This discussion subscribes to the latter characterisation.

The born-frees are not a homogenous generation. There are who that are at the universities. Others, because of their socioeconomic circumstances, loiter in the streets.

The political generation’s theorists are unanimous in their assertions that the born-frees are different from the struggle generation in many ways. As Mattes explains, the born frees are “more modern, with higher levels of education”, urbanised and “cosmopolitan in their outlook” than the struggle generation.

A significant part of the struggle generation’s activism was inspired by Biko’s Black Consciousness philosophy from the late 1960s. The philosophy spawned radicalism characterised by confrontation with the apartheid machinery. The epochal June 16, 1976 students uprisings are a case in point. The students’ revolt breathed new life into the moribund struggle for liberation.

But why are the born frees increasingly attracted to Biko’s Black Consciousness philosophy in post-apartheid South Africa? Why are they being radicalised when they should be enjoying the fruits of democracy brought by the struggles of the previous generations?

Long-lasting legacy of influence

To understand the reason for the growing attraction to Biko’s views and their continued relevance, we should ask: did black people attain, in Biko’s words, their “envisioned self which is a free self” in 1994 and “rid themselves of the shackles that bind them to perpetual servitude”?

The born frees increasingly think not – especially those in the lowest strata of society, unable to afford a tertiary education, facing a bleak future and feeling alienated.

They question the very concept of freedom and being born free as an oxymoron. These concepts have failed to instil a sense of pride in their blackness. Officialdom’s response is to spew statistics that seemingly prove performance by the state, largely in dispensing the largesse.

In many ways this trivialises the complexity of the post-apartheid society, following many years of apartheid colonialism. Various instances of making blacks feel inferior challenge the state performance narrative as, in the words of critical theorist Donaldo Macedo, “the pedagogy of big lies”.

Theologian Ndikho Mtshiselwa argues that the fundamentals of the apartheid colonial social order are still in place, with the democratic regime unwittingly administering them, instead of changing or providing leadership in their destruction.

This is the irony of South Africa’s transition from apartheid colonialism, which gave the colonial matrices of power the space to, in decoloniality scholar Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni’s words:

… continue to exist in the minds, lives, language, dreams, imaginations and epistemologies of modern subjects.

As long as this situation exists, Biko’s philosophy of black pride continues to be relevant. As Biko said:

It seeks to infuse the black community with a new-found pride in themselves, their efforts, their value systems, their culture, their religion and their outlook to life.

Two decades into South Africa’s democracy, the rise of largely born-free movements such as #RhodesMustFall and Open Stellenbosch, which transcend party-political affiliations, expose the limitations of the transitional arrangements from which the post-apartheid state was constructed.

In ways reminiscent of Biko’s Black Consciousness movement, these challenge the colonial matrices of power which eluded the making of the post-apartheid state. The matrices foster institutional racism based on Hegelianism - a body of thought that characterises the cognitive faculty of Africans as, in Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Diagne’s words in The Meaning of Timbuktu, the “other reason and philosophical spirit” is bereft of the “capacity to think and live by a consistent system of sound principles”.

This is what students at the universities of Cape Town and Stellenbosch are fighting against. Their struggle seeks to restore and assert black pride – the essence of Biko’s philosophy of Black Consciousness.

The same spirit exists at the University of the Witwatersrand, where Western epistemology is increasingly being challenged in the debate on curricula transformation.

The born-frees are grappling with the question of the meaning of freedom in post-apartheid South Africa. They seek an antidote to their reality wherein blackness continues to be mocked and marginalised.

Their reality is one in which language policy is overtly used to limit the number of black students at historically white universities. They also have to contend with situations whereby white students enjoy privileged status under the guise of dual language instruction to perpetuate the falsehood of separate but equal.

This much is evident in the accounts of 32 students at the University of Stellenbosch in the online documentary #Luister.“Luister” is Afrikaans for listen.

The struggles of the born-frees beg the questions:

Hasn’t the struggle generation betrayed its children with the architecture of the post-apartheid state?

Did it err when it focused more on political transformation to the detriment of social and economic dimensions?

Hasn’t the “Rainbow Nation” invention unwittingly normalised coloniality?

The cries of black students expose a failure to adequately situate the theoretical and strategic policy orientations of the post-apartheid transformation agenda in Biko’s Black Consciousness philosophy. As long as black pride is not attained in post-apartheid South Africa, Biko’s philosophy remains relevant. Its transcendence continues to connect generations.

The article has been updated to reflect the 40th anniversary of Biko’s death.